Militia

Essay

As the social and political center of colonial Pennsylvania, Philadelphia and the surrounding region served as a microcosm for the complex and often convoluted history of the colonial and early national militia. The role of Philadelphia militia also illustrates the nature of militia units during the American Revolutionary War.

The first militia in the region that became Pennsylvania formed in 1671 in accordance with the Laws of the Duke of York, but the conflict between compulsory military service and the pacifist principles of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) quickly sparked controversy. Pennsylvania founder William Penn (1644-1718) retained the right to create a militia in the event of an emergency, but theological and political conflicts prevented passage of long-lasting militia regulations. From 1671 to 1776, the Pennsylvania Assembly passed several militia acts but allowed them to expire, mostly due to Quaker influence and the highly politicized nature of mandatory military service. When temporary militia companies came into existence, they remained voluntary, relatively few men attended mustering events, and they quickly disbanded.

In colonial New Jersey and the eventual state of Delaware, the Dutch formed the earliest militia companies in the 1640s with the intention to defend settlers and trading centers from raids from foreign powers and Native Americans. The geography of New Jersey, with the Delaware River acting as a natural bulwark, eventually relieved the area from threats from European or Native forces. Although the New Jersey legislature formally allotted funds to train militia companies in 1668 and 1744, militia groups remained relatively small and localized.

Increasing Indian attacks against settlers made Pennsylvania one of the main areas of conflict during the Seven Years’ War (French and Indian War, 1756-63). Lacking the long-term legislative militia regulations of other colonies, Pennsylvania had to scramble to muster fiercely independent and often far-flung colonials into organized militia units. The Pennsylvania assembly passed the Militia Act of November 25, 1755, but units formed slowly that fall and winter, and under the law they could not be marched more than three days beyond the settled parts of the province, left in garrison frontier forts, or be punished with military discipline. To supplement the militia, the act also provided for a Provincial Army of voluntary, paid “Associators,” but they also remained near their communities. In New Jersey, Indian raids along the northern border of Pennsylvania and New York prompted formation of the “Jersey Blues” militia regiment, which saw combat at some of the most significant battles of the conflict, including the Siege of Fort William Henry and the capture of Montreal.

Volunteers Militias

During the era of the American Revolution, Philadelphia became home to a large number of militia companies that eventually served the Continental Army. However, Pennsylvania’s longstanding tradition of opposing compulsory military service hampered the formation of a large-scale militia network. In the absence of well-established state regulations, groups of affluent citizens sympathetic to the Patriot cause formed volunteer militias that fell outside the authority of the state Assembly. Among these were the Philadelphia Associators (formed 1747) and the First Troop Philadelphia City Cavalry (formed 1774).

The first callout for patriot militia units in Philadelphia, issued by the Continental Congress in December 1776, was strictly voluntary and produced a very poor turnout. At the behest of General George Washington (1732-99), the “Act to Regulate the Militia of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania” in March 1777 required all able-bodied men ages 18 to 53 to serve tours of two months, established strict draft conditions, and levied heavy fines and penalties against those unwilling to participate. Battalions elected their own officers for three-year terms, and County Lieutenants (not a military rank) enforced the regulations within their communities. Under these conditions, eight militia battalions of roughly one hundred soldiers per battalion formed in Philadelphia and the surrounding counties.

Nevertheless, familiar controversy about military service continued as religious groups such as the Free Quakers philosophically abstained from soldiering. Quaker pacifists, perceived as unpatriotic and loyalist, were zealously targeted for fines and punishments. In 1779, Pennsylvania increased fines for failing to participate to more than six times the previous penalty.

In New Jersey, large numbers of patriots as well as loyalists led to the creation of militia on both sides of the conflict. During the summer of 1775, the New Jersey Provincial Congress passed a militia act calling for all men, ages 16 to 50, to form local regiments to fight against the British. Unlike the militia regulations of Pennsylvania, participation was voluntary. Twenty-six militia regiments of sixty to eighty men each formed across the state, including two in Gloucester and one in Salem County. Meanwhile, approximately three thousand loyalists formed the “New Jersey Volunteers” and fought as auxiliaries for British forces at some of the largest engagements of the Revolution, including the Battle of Monmouth (1778). Throughout the war, patriot and loyalist militia clashed in small skirmishes and raids as British forces and their auxiliaries foraged for food and supplies across the Garden State.

Delaware’s Militias

At the onset of the American Revolution, several private and county militia companies already existed across the state of Delaware. At the request of the Continental Congress, a “flying camp’ of 450 Delaware militiamen joined the Continental Army outside of Perth Amboy, New Jersey, in October 1776. The Delaware militia participated in the Battle of Long Island and saw continued action throughout the war against British and Loyalist troops across the state.

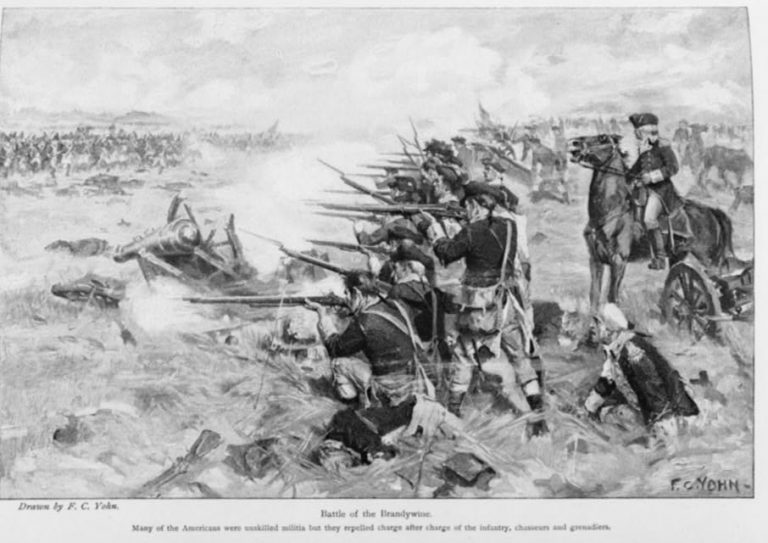

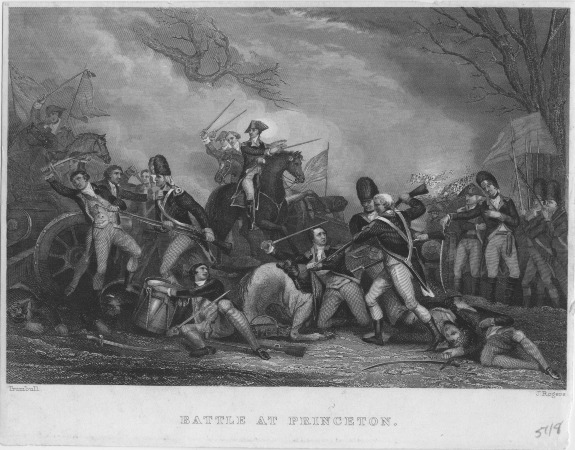

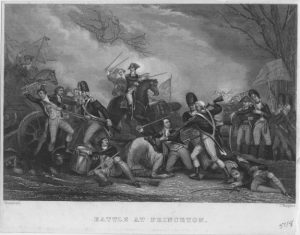

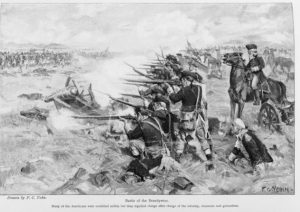

In the field, volunteer and state militias from Philadelphia participated in some of the most pivotal engagements of the northern theater of the war, most notably during the campaigns of 1777-78. Militia companies and volunteer military groups mustered from the Philadelphia area took part in the battles of Trenton, Princeton, Brandywine, Germantown, White Marsh, and Red Bank, as well as in small skirmishes along the Schuylkill River. During the British occupation of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and New Jersey militia manned the Patriot-held Delaware River forts, which were critical for harassing British supply convoys and keeping General William Howe (1729-1814) from reinforcing his beleaguered garrison. After the British withdrew from Philadelphia following the occupation of 1777-78, the First Troop Philadelphia City Cavalry became the first patriot military unit to enter the city.

In the aftermath of the occupation, the Pennsylvania Supreme Executive Council called on several militia classes for garrison duty amid fear of danger posed by remaining British sympathizers and collaborators with the Crown. However, this did not deter unrest over issues such as the price of essential foodstuffs and other goods. Frustration extended to elements of the militia and boiled over in October 1778 as militiamen rioted and attacked the home of James Wilson (1742-98), a prominent lawyer who defended perceived loyalists and British collaborators from property seizure by Patriot courts. After a brief but violent confrontation in which several militiamen were killed, the First Troop Philadelphia City Cavalry restored order.

As the war moved south for the remainder of the Revolution, the Pennsylvania militia deployed to frontier areas to deter Indian raids and guarded powder magazines and supply depots across the Delaware River Valley. After the British surrendered at Yorktown in 1781, the First Troop Philadelphia City Calvary delivered the captured British standard to Congress at the State House (Independence Hall).

Militias Under the Constitution

The militia for the new nation diverged significantly from the colonial system. The Articles of Confederation and the Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution called for the formation of state militias in lieu of a permanent standing army. Similarly, the Pennsylvania Constitutions of 1776 and 1790 expressly stated the danger of a standing army in peace time and based the defense of the state on militia companies. In 1792, during Philadelphia’s decade as the nation’s capital, the U.S. Congress passed a Militia Act requiring each state to maintain militia units and authorized the president to call and command state forces (as President Washington did during the Whiskey Rebellion in 1794). Philadelphia companies participated in military engagements against foreign aggressors and civil emergencies throughout the nineteenth century, including the War of 1812 and the Nativist Riots of 1844.

Following the Civil War, the existing Pennsylvania militia companies formally consolidated in a single division known as the “National Guard of Pennsylvania.” Several prominent Philadelphia military organizations with lineages dating back to the Revolution became folded into the statewide body, including the First Troop Philadelphia City Cavalry, Washington Grays of Philadelphia (1822), and the Philadelphia Associators. While similar in name to the later U.S. Army National Guard, the “National Guard of Pennsylvania” remained semi-independent until the twentieth century.

The militia system that originated in the colonial era officially ended in 1903, when the federal Efficiency in Militia Act made the National Guards of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, and other states subordinate to the U.S. Army and organized, trained, and equipped them along the same standards. Replacing the obsolete Uniform Militia Act of 1792, the legislation established the modern Army National Guard. Service in state guard units now required enlistment in the U.S. Army, with officers commissioned by the federal government instead of elected by regiments.

During the late twentieth century, small bands of civilians, not affiliated with the U.S. military or state or federal governments, formed private militias groups with varied political agendas. These groups, often ultraconservative and anti-government, often promoted mythological, often apocryphal versions of colonial militias’ histories that diverged the complex social and political entities of the colonial era and early republic. Running the gamut from loosely knit social clubs to highly organized units such as the Pennsylvania Military Reserve, some groups became tied to violent actions against the state and federal governments.

Dating to the colonial era, the long tradition of a militia system for the region’s common defense stood in contrast with the disdain for large standing armies. Militiamen in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware defended their homes and families from a myriad of native and foreign opponents and fought with distinction during the War for Independence. Although militiamen at times shirked responsibilities, disregarded military hierarchy, and deserted en masse in the face of defeat, the militia nevertheless had a profound effect on the political, military, and cultural history of the region.

William V. Bartleson is an independent scholar of military history who has worked with the New Jersey National Guard Militia Museum and the Center for Veterans Oral History. He is a member of Phi Alpha Theta. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Delaware National Guard service is a family affair (WHYY, January 25, 2012)

- Pa. National Guard troops wrapping up storm-recovery missions (WHYY, November 12, 2012)

- Volunteers search for traces of history beneath Lovett Park (WHYY, November 26, 2012)

- Feds exploring ways to preserve Revolutionary War-era home (WHYY, October 19, 2016)

- Delaware National Guard in DC for presidential inauguration (WHYY, January 19, 2017)

Links

- Historical Highlights of the Pennsylvania National Guard (Pennsylvania National Guard)

- Washington Grays Monument (Association for Public Art)

- The Philadelphia Washington Grays' Two-Step (Library of Congress)

- Revolutionary War Militia Battalions and Companies (Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission)