Monopoly

Essay

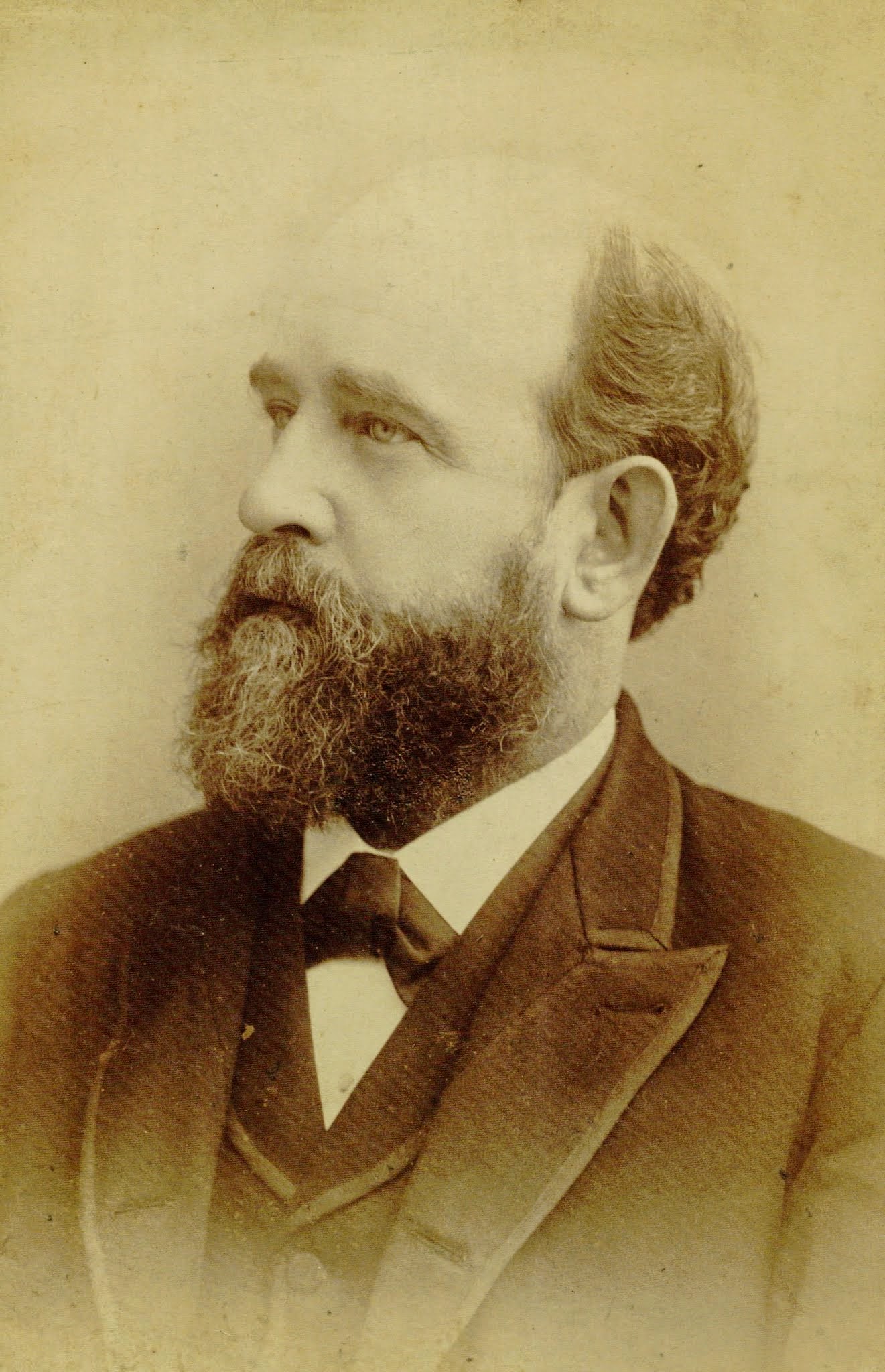

Although an unemployed Philadelphia salesman, Charles Darrow (1889-1967), was long credited as the creator of the world’s most popular board game, the origins of Monopoly stretch several decades before Parker Brothers purchased the rights from Darrow in 1935 and beyond the iconic streets of Atlantic City featured in the game. The proper history of Monopoly began in the early 1900s when a stenographer living near Washington, D.C., Elizabeth “Lizzie” Magie (1866-1948), created a game to demonstrate the destructive and anti-social nature of monopolies as outlined by the famous nineteenth-century political economist Henry George (1839-97). Magie called her invention The Landlord’s Game.

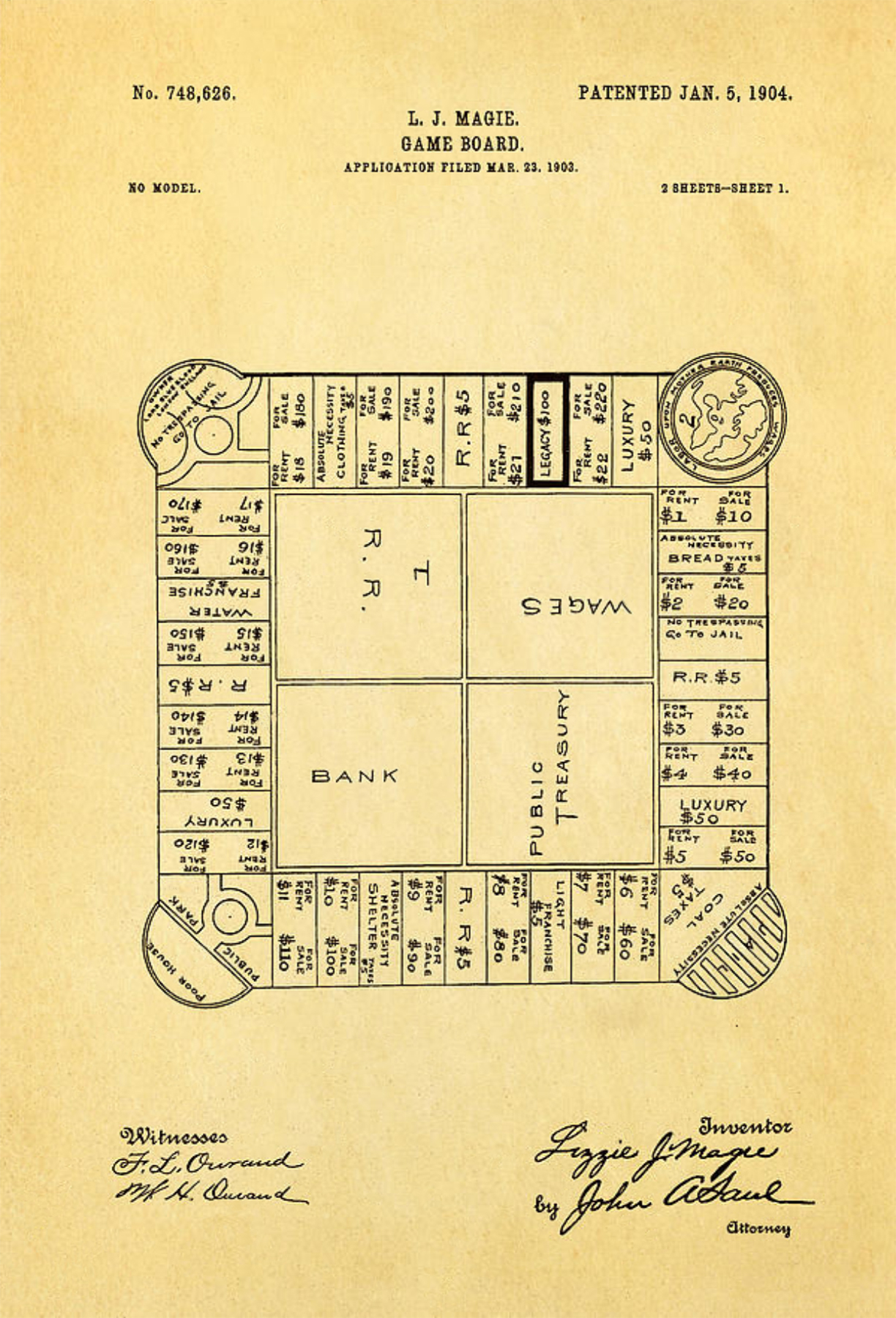

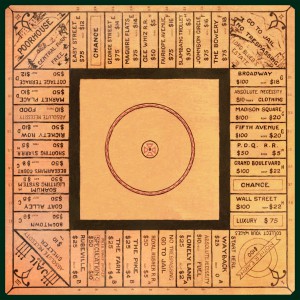

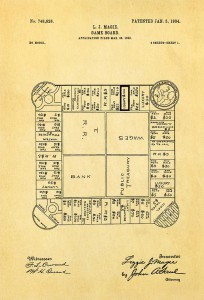

The object of The Landlord’s Game was to obtain money and wealth by purchasing properties, charging rent, and creating monopolies. Magie’s square board included twenty-two property deeds, four railroads, two public utilities, and four corner spaces. She labeled one of her corner spaces “Mother Earth.” Each time players passed Mother Earth they collected $100 in wages. Magie patented her game in 1904.

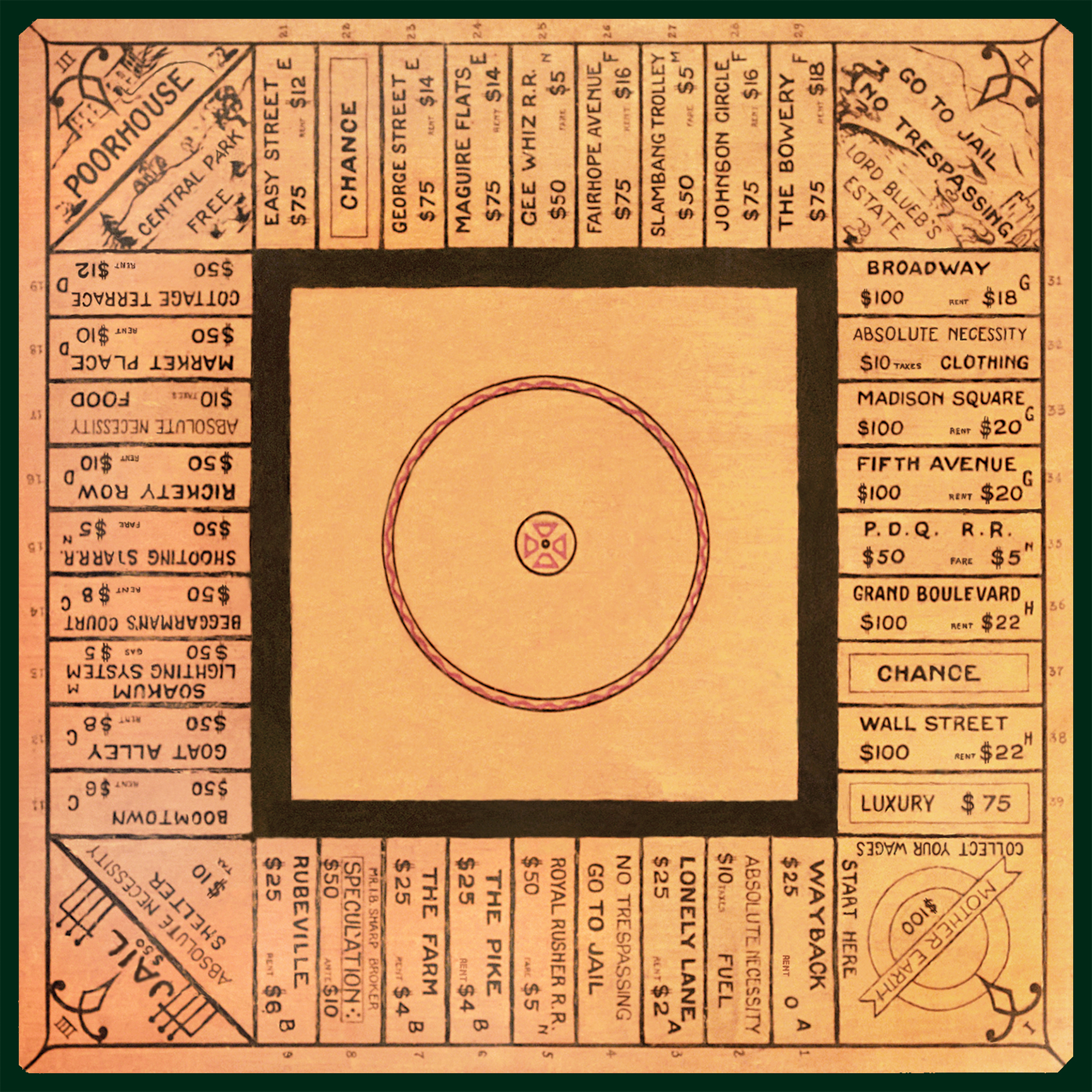

Magie introduced The Landlord’s Game to family and friends, including the residents of Arden, Delaware—a utopian community formed in 1900 to demonstrate the virtues of Henry George’s land and tax theories. The Arden residents who played The Landlord’s Game included author Upton Sinclair and economics professor Scott Nearing. Nearing taught the game—which he called “monopoly” or “the monopoly game”—to his students at the Wharton School and the University of Toledo. As Magie’s game spread to different locations, players added to the original board and changed the names of the properties to forge more personal connections to the game.

Monopoly came to Atlantic City in 1929 via Ruth Hoskins, a teacher at the local Friends School. Hoskins, who had first played the game in Indianapolis, showed it to her friends and fellow Quakers Cyril and Ruth Harvey. The Harveys loved it and soon began hosting weekly game nights. They also renamed the properties after streets in Atlantic City that had personal meaning for them. As the author Mary Pilon (b. 1986) explained in her book The Monopolists, the Harveys lived on Pennsylvania Avenue, had friends who lived at Park Place, and once employed a maid who lived on Baltic Avenue near Mediterranean Avenue. Jesse Raiford (1900-60), an Atlantic City real estate agent and friend of the Harveys, helped assign new values to the properties, which he grouped by color, and built wooden boxes to use as houses.

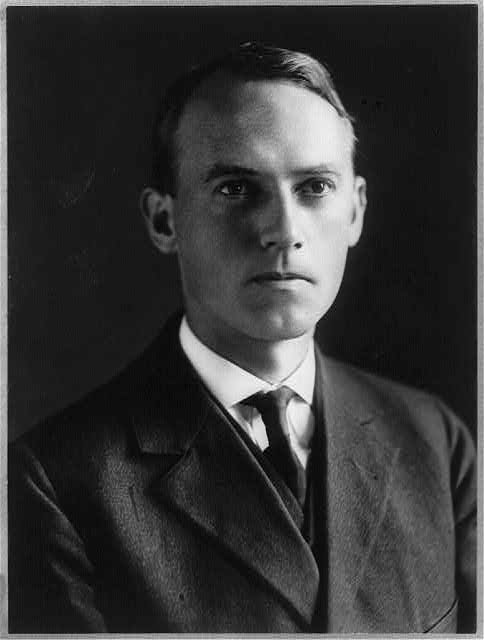

Charles Darrow first played the Quakers’ Atlantic City version of Monopoly in 1933. Unemployed and on the hunt for a new hobby, he immediately became obsessed with the game. Darrow asked his friend and artist Franklin Alexander (1925-2007) to draw a new and more richly illustrated version of the board, which he then patented and began marketing. In 1935 he sold his patent to Parker Brothers for $7,000 plus royalties. When executives at Parker Brothers pressed Darrow for the details of Monopoly’s creation, he insisted that the game was his “brain child” created for the “sole purpose of amusing myself.”

Although Parker Brothers doubted Darrow’s claim to have invented Monopoly, the company successfully peddled it as part of the game’s official creation story. Partly due to Monopoly’s instant success—Parker Brothers sold more than 1.7 million units in 1936—and party due to the ferocity with which the company stamped out any potential competitors, Darrow soon became well-known as the sole inventor of Monopoly.

Those who had played or seen earlier versions of Monopoly and The Landlord’s Game challenged Parker Brother’s title to the game, pointing out that Monopoly had been in the public domain for thirty years before Darrow supposedly created it. One of those challengers was Ralph Anspach, an economics professor living in Northern California who invented the game Anti-Monopoly. In 1973, General Mills (which acquired Parker Brothers in 1968) successfully sued Anspach for copyright infringement. On appeal, however, Anpsach prevailed and in the process helped make the true origins of Monopoly more widely known.

In Anti-Monopoly Inc. v. General Mills Fun Group Inc., decided August 26, 1982, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit invalidated Parker Brothers’ Monopoly trademark, writing that “the evidence clearly shows that the game of monopoly was played by a small number of people before Darrow learned of it, and that these people called the game ‘monopoly.’” As such, the Court continued, “as applied to a board game, the word “Monopoly” has become “generic,” and the registration of it as a trademark is no longer valid.”

While Parker Brothers no longer claims Darrow invented the game, it still celebrates 1935 as the year of Monopoly’s public debut. In honor of the game’s eightieth anniversary in 2015, Hasbro Inc.—which purchased Parker Brothers in 1991—released a “retro” edition of Monopoly featuring game cards and tokens from the 1930s. For a truly “retro” Monopoly experience, however, players would need to find a copy of The Landlord’s Game.

Alexandra W. Lough holds a Ph.D. in American History from Brandeis University. She is the director of the Henry George Birthplace, Archives, and Historical Research Center. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- Monopoly Patented (Library of Congress)

- Monopoly: Financial Prosperity in the Depression (Pennsylvania Center for the Book at Pennsylvania State University)

- Monopoly Game History, Landlord's Game History (Landlordsgame.info)

- Anti-Monopoly Inc. v. General Mills Fun Group Inc.: Ending the Monopoly on Monopoly (PDF, Loyola Marymount University)

- Ever Cheat at Monopoly? So Did its Creator: He Stole the Idea from a Woman (National Public Radio)