Public Health

Essay

From the moment Native Americans, Europeans, and Africans came together in the Delaware Valley, they confronted a host of health threats. Philadelphia’s earliest public health efforts reflected the lack of scientific understanding of infectious diseases, and usually began only after an outbreak commenced. After the terrible 1793 yellow fever epidemic, Philadelphia’s leaders founded a permanent Board of Health that endured into the twenty-first century as the Department of Health. By the late twentieth century, public health efforts in the region, which included regulations intended to improve housing, food quality, and associated environmental standards, as well as private efforts to help the poor, had long since transitioned from a war against miasma and microbes to campaigns to stem the rising deaths associated with lifestyle choices.

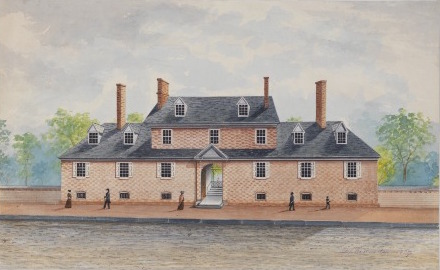

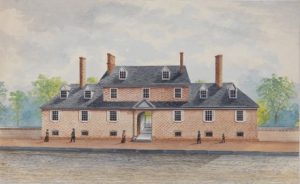

Eighteenth-century Philadelphia experienced numerous threats to health and had almost no effective medicine. Lack of scientific knowledge limited public health efforts, too. Still, medical and civic authorities took action when particularly fearful diseases emerged. As early as 1700, the city instituted a regime of ship inspection on the Delaware River and by 1720 designated a doctor as port physician charged with regular inspection of vessels for signs of disease among crew and passengers. By 1743, the city built a lazaretto, or pest hospital, on Province Island, at the confluence of the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers, for the purpose of quarantining the sick who arrived by ship. As the century wore on, officials recognized the need for a maritime quarantine station further down the Delaware, away from the growing city. It opened a new lazaretto in Tinicum in 1801, which operated until the end of the century.

Private efforts to curtail disease included the Quakers’ Friends Almshouse, opened in 1713 for the exclusive use of destitute Friends. The City of Philadelphia later opened a charity hospital to care for the sick poor attached to the Philadelphia Almshouse, in 1732, which vied with Pennsylvania Hospital, opened on High Street in 1751, as the first hospital in the colonies. The almshouse and hospital moved to a new location, on Spruce and Eleventh Streets, in 1767. The hospital cared for many patients during epidemics and treated Continental Army soldiers who, in 1778, were hit with an outbreak of dysentery. In 1786, Benjamin Rush established the Philadelphia Dispensary on Fifth Street and charged it with caring for ill paupers, provided they did not suffer from venereal disease or delirium tremens. The Southern and Northern Dispensaries, founded in 1816 and 1817, respectively, joined the Philadelphia Dispensary in the effort to provide outpatient treatment to citizens of modest means.

Epidemics could prove catastrophic, killing hundreds, and sometimes thousands, in just a few months. In the city’s early years, it formed ad hoc boards of health during outbreaks, and these well-intentioned citizens turned to a mixture of responses, from the useless burning of smudge pots filled with sulfur and urine-soaked straw, to the incineration of the possessions of the dead; sometimes they razed the homes themselves. The boards also turned to the time-honored quarantine order, confining the sick to their homes or, especially in the case of the poor, to the almshouses and city-managed hospitals, where they died in huge numbers. Though mortality rates among the quarantined were high, isolation did provide a measure of protection for the community against contagious diseases.

Yellow Fever, 1793

In 1793, however, mosquito-borne yellow fever demonstrated the limits of quarantine. The disease settled over the city in the late summer and early autumn, infecting thousands. Along with the usual round of public health measures, the city commandeered Bush Hill, a vacant estate at the edge of the city, as a quarantine and treatment facility. Such public health efforts, however, did not avert the death of between five and six thousand residents, or more than 10 percent of Philadelphia’s population.

This epidemic, and outbreaks in 1798 and 1806, catalyzed changes to Philadelphia’s public health apparatus. In 1794, the city formed a permanent Board of Health. In 1808, the board began to record the number of deaths from smallpox and a few other diseases. When cholera entered the city in 1832 and 1848, it sent out orders for useless cleaning of gutters and streets. More importantly, it again established an emergency hospital at Bush Hill, but, like at the almshouse and hospital, hundreds of patients endured indescribable conditions. Authorities later reported that “the nature of cholera,” which was marked by complete evacuation of the alimentary canal by uncontrollable, explosive diarrhea and vomiting, horrified attendants such that they fled in disgust and fright.

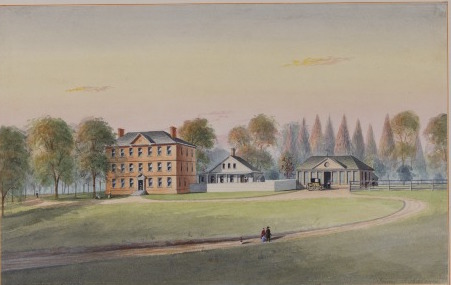

Yet, even as cholera stalked the city, a new era of public health began to dawn in Philadelphia. By 1835, the Philadelphia Almshouse moved to Cleveland Avenue and Thirty-Fourth Street, in West Philadelphia, and within a few decades was joined by the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Medicine. Just blocks from the new almshouse and charity hospital, it used the hospital as a training ground for its physicians and nurses. In 1837, the almshouse, nicknamed Blockley Hospital because of its location in the old township of that name, prevented the malnutrition of thousands of residents who suffered during the economic panic that year. The Board of Health began to register birth, deaths, and marriages in the city in 1860, gathering the basic data required to systematically tackle health threats. In 1865, Philadelphia opened the Municipal Hospital for Contagious Diseases at Twenty-Second and Lehigh Streets to replace the ad hoc Bush Hill estate hospital. This new hospital isolated patients suffering from the most severe and contagious diseases, especially the indigent poor who risked spreading disease in the crowded wards of Blockley.

The physical structure of cities underwent vast changes during the late nineteenth century, and many of those changes had an impact on health. In Philadelphia, streets of granite blocks and asphalt replaced those of cobblestone or packed earth, which made street cleaning immeasurably easier. Rubbish collection and street cleaning, when done well, reduced the population of rats, scavenging dogs that transmitted rabies, and flies, whose travels took them from trash, to feces, to food and thereby spread typhoid and other disease. The city began to better regulate cesspool cleaning, too, which, by the late 1870s, was supposed to be accomplished with airtight, leak-proof pumps and containers—though many carriers still employed leaky carts—and only during daylight hours, in order to facilitate inspection by city sanitary officers and concerned reformers alike. Real improvement in effluvia removal began when the city accelerated the construction of sanitary and storm sewers during the last few decades of the nineteenth century and ordered housing near sewers to connect to them, a development that ushered in the era of the modern toilet. By 1900 the city had eight hundred miles of sewage pipe. In the 1880s, Philadelphia, renowned for its lack of New York–style tenement buildings, increased housing regulations and inspections, paying particular attention to ventilation and drainage in the poorer sections of the city.

A Revolution in Public Health

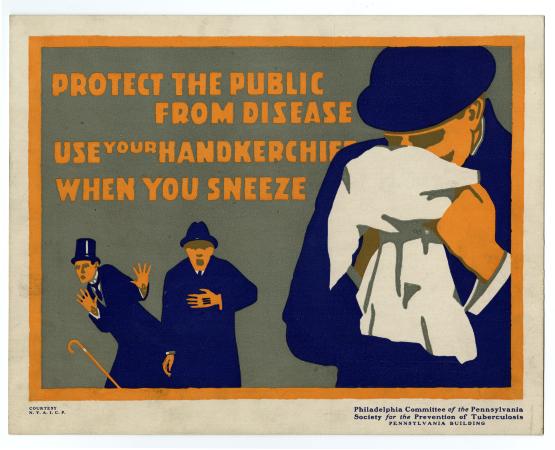

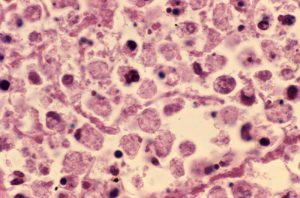

The bacterial revolution of the mid-nineteenth century culminated in the determination by Louis Pasteur (1822–95), Sir Joseph Lister (1827–1912), and Robert Koch (1843–1910), among others, that microbes caused many diseases. After a rash of discoveries in the 1870s and 1880s uncovered the pathogens associated with anthrax, tuberculosis, and typhoid, effective remedies in the form of antitoxins, water filtration and chlorination, and isolation of the sick began to revolutionize public health. In 1887, half a dozen physicians and professional sanitarians replaced the two dozen members of the Philadelphia Board of Health, a move that, while reducing the number of managers, increased the expertise of the organization. The board moved to enforce vaccination of school children against smallpox in 1895, began to manufacture diphtheria antitoxin, and advocated the chlorination of the city’s water supply, which was completed in 1912. Cleansing of the city’s water reduced deaths from waterborne illnesses to near-modern levels and saved hundreds, perhaps thousands of lives every year. In 1894, the board mandated that all milk sold in the city be obtained only from cows it certified as healthy. In 1895, it built a bacteriology lab and also ordered the placarding of the homes of patients with serious contagious diseases.

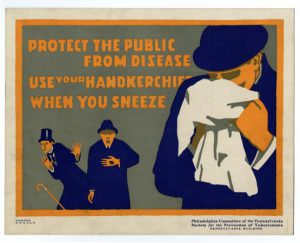

In the early twentieth century, private organizations continued to provide ever more sophisticated public health services. Private groups offered visiting nurses services throughout the Philadelphia metropolitan area. Some, like Presbyterian Hospital’s School of Nursing, visited homes as an extension of their educational and clinical efforts, while others, for instance the Visiting Nurse Society of Philadelphia, were founded by nurses specifically for the purpose of home visitation, administering care to laboring families who could ill-afford medical care, especially for sick children. Visiting-nurses programs also aided mothers by providing proper nutrition and advice about hygiene and other childcare concerns. In Philadelphia, some private hospitals opened clinics that rendered both general and specialized care to the poor. St. Joseph’s Hospital, for instance, established free gynecological and obstetric care. The Board of Health also established health centers in conjunction with nurses and neighborhood physicians, an early attempt to synergize municipal public health efforts with private physicians; when a health center diagnosed a medical concern and determined a family could pay a physician, it made a referral, otherwise the city provided the service.

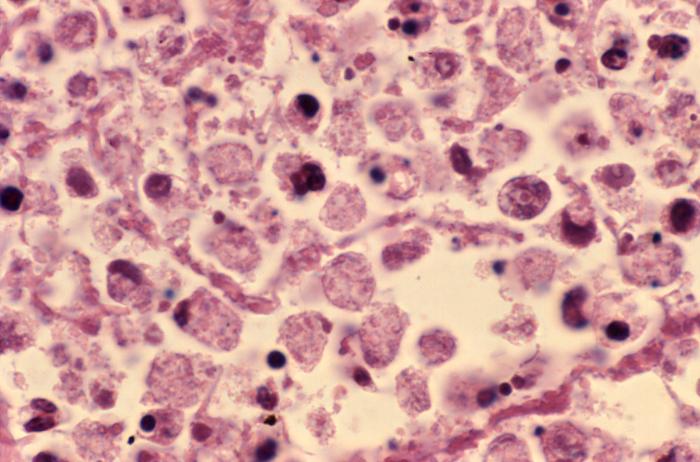

Though many other diseases captured the imagination and provoked terror in the population because of their symptoms, it was tuberculosis that ranked as the greatest killer during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The density of people in Philadelphia’s poorer areas allowed for efficient transmission of the bacteria that causes TB. The disease could also be contracted from milk from infected cows, which resulted in tuberculosis of the bowel. By 1892, the Anti-Tuberculosis League of Philadelphia organized to educate policy makers and the public about the dangers of the disease. The city also issued increasingly stringent pure milk requirements throughout these years. The most important measure against tuberculosis came with the founding, in 1905, of the state Department of Health, whose head for the first dozen years, Samuel G. Dixon (1851–1918), was a noted tuberculosis researcher. Dixon opened three large sanitaria and hundreds of dispensaries that, when allied with municipal TB clinics in the region, treated or removed to one of the state’s three large, rural tuberculosis sanitaria, thousands of cases from Philadelphia and surrounding Pennsylvania counties every year. New Jersey and Delaware, too, had anti-tuberculosis programs, but none were as extensive, or expensive, as Pennsylvania’s. City public health leaders also focused more attention on mental health, with the construction of Byberry Mental Hospital on Roosevelt Boulevard and Southampton Road in 1907, though standards of care there would shock later sensibilities.

Global Influenza

The greatest challenges to the public’s health in the early twentieth century emerged when the virus responsible for a global pandemic of influenza swept across the region between 1918 and 1919. Unfortunately, Philadelphia decided to go ahead with plans for a massive patriotic parade in the midst of this epidemic and the result was the most acute urban outbreak in the nation. The city responded with every weapon at its disposal, including quarantine, emergency hospitals, and calls for thousands of volunteers, literally the largest public health action in the city’s history. The effort was coordinated and powerful. Nonetheless, the highly infectious, airborne virus with no antidote proved beyond the capabilities of any health body to control, and at least thirteen thousand died in just six months. The Board of Health also confronted polio during the First World War, with isolation of patients and families the protocol.

During the 1950s and 1960s, the advent of sulfa drugs and penicillin, as well as a host of inoculations, increasingly delivered not by public health workers but by private physicians, reduced the importance of government-provided public health efforts in the post–World War II era. For a time it appeared as though public health efforts would be permanently relegated to aiding the poor and addressing hygiene standards in public establishments. In the late twentieth century, however, the emergence of Legionnaires Disease and Swine Flu, both of which began in 1976 in Philadelphia and South Jersey, again prompted local public health entities to spring into action. Swine Flu provoked a regime of mass immunization in the region and across the nation. Worse followed in 1981 when gay men and, in very short order, intravenous drug users and hemophiliacs presented with symptoms of immune system collapse. By 1983, Philadelphia formed its first HIV/AIDS task force, while New Jersey instituted the nation’s first AIDS Awareness Month in February 1983.

Other public health initiatives advanced by both public and private organizations included a smoking cessation campaign, with bans on smoking in most public spaces passed by city council in 2006, bans that eventually included parks and all city-owned recreation centers, restaurants, bars, and all public buildings and their entrances. In the early twenty-first century, public health efforts expanded to include preparations in the case of a terrorist attack and initiatives to fight a rising tide of opiate addiction and drug overdose and to counter the increasing abuse of prescription painkillers. Diseases such as diabetes and heart disease led to new prevention and treatment campaigns aimed to inform citizens of the ways they could avoid or control disease through lifestyle changes. To aid the community, in the early twenty-first century the city proposed measures that would place an additional tax on certain sugary foods, most importantly soda and other high calorie beverages, and mandate listing of calories on the menus of chain restaurants.

Public health efforts in Philadelphia and the region mirrored those found throughout the nation, with Philadelphia, especially during the colonial era, leading the way by implementing some of the earliest public health efforts. Philadelphia’s public health measures reflected the growth of scientific knowledge over the course of more than three hundred years of discovery and practice. Public health leaders and organizations who once primarily responded to infectious disease outbreaks, later aided in changing the physical environment of the city and the region as a means of disease prevention, and then combated a mix of chronic diseases, addiction, and emerging pathogens, such as West Nile virus, Zika virus, and multiple influenza scares. Even in the face of an increased emphasis on private medicine, public health organizations continued to evolve to meet new challenges. The region’s public health efforts benefited, too, from an increased federal role in public health, including NIH/CDC responses to infectious disease outbreaks, Medicaid/and Medicare for the poor and elderly, and an array of federal health standards and agencies that enrich the quality of health in the region.

James Higgins is a lecturer in American history at the University of Houston–Victoria. He specializes in the history of medicine, especially as it pertains to Pennsylvania. His manuscript, which analyzes four urban outbreaks in Pennsylvania during the 1918–19 influenza pandemic, is with the University of Rochester Press. He has offered a dozen conference papers and several articles, invited lectures, and book chapters.

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Polio vaccine developer, Dr. Hilary Koprowski, dies at 96 (WHYY, April 14, 2013)

- Bacteria found in Wilmington's drinking water (WHYY, September 6, 2013)

- Flu vaccine required for many area health workers (NewsWorks, November 18, 2013)

- Hundreds of Princeton students seek meningitis vaccine (WHYY, December 9, 2013)

- 60th anniversary of polio vaccine, first administered in Pa. (WHYY, April 15, 2014)

- Talking zoonoses with Philadelphia's Public Health Nerd Club (WHYY, May 29, 2014)

- One couple's strategy for waging a personal, public health campaign (WHYY, April 23, 2015)

- North Philadelphia hospital to close (WHYY, December 30, 2015)

- A fool's errand? Eliminating mosquitos to end disease epidemics (WHYY, June 9, 2016)

- How Philly's winning soda tax strategy left out the public health angle (WHYY, June 23, 2016)

- 40 years later, scientist who first discovered Legionnaires' disease is still learning lessons (WHYY, July 28, 2016)

- Reshuffling resources and tapping enthusiasm, Philly launches kids health initiative (WHYY, July 11, 2017)

Links

- Inside Pennsylvania Hospital's Little Seen Original Building (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Visiting Nurses' Society of Philadelphia (pdf, University of Pennsylvania)

- Lazaretto Quarantine Station Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- PhilaPlace: Philadelphia General Hospital (Old Blockley): Philadelphians "Ain't Goin' to no Bellevue" (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Hats Off To Stetson's Union Mission Hospital (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- With the Best of Intentions: Byberry Asylum (Pennsylvania Center for the Book at Pennsylvania State University)

- A Haunting Place (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Fever 1793: With Capital In Crisis, Stephen Girard Rises To The Occasion (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Bacteria And The Bellevue: The Birthplace Of Legionnaires’ Disease (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- PhilaPlace: Philadelphia General Hospital (Old Blockley): Philadelphians "Ain't Goin' to no Bellevue" (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Take Care of Him and I will repay Thee: A Luxurious Philadelphia Asylum (PhillyHistory Blog)

- 1918: Death on the Home Front (PhillyHistory Blog)