Refineries (Oil)

By Carola Hein

Essay

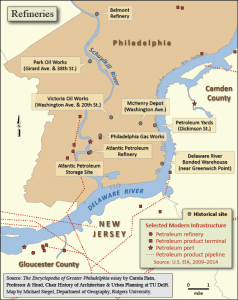

Philadelphia emerged as a petroleum hub in the second half of the nineteenth century. As an industrialized port city with global networks and extensive unbuilt land available on the Schuylkill and Delaware Rivers, the city offered the necessary rail and water infrastructure as well as access to water for the new industry. Extensive construction of refineries, storage tanks, pipelines, and railway lines began in the 1860s. Once consolidation of the refineries on a handful of sites, notably on the Schuylkill, was complete, the oil industry presence continued to influence spatial decisions into the twenty-first century.

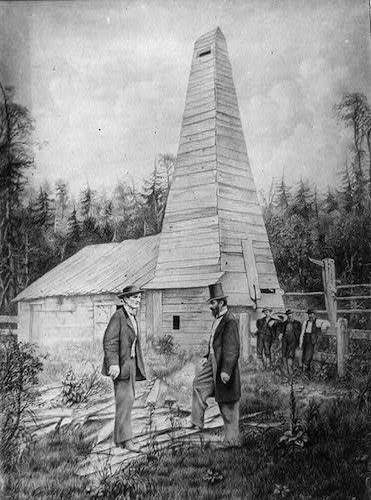

The American oil story began in western Pennsylvania, where Edwin Drake (1819-80) drilled for oil in 1859, but the natural resource had to be transported elsewhere to be refined and ultimately consumed. As consumers discovered new uses of petroleum— in particular, it was quickly replacing whale oil for lighting— new businesses rapidly expanded storage, refining, and shipping capacities. The production of oil increased from some 4,450 barrels in the first year, to 220,000 barrels in 1860 and 2,114,000 barrels in 1861, almost a 500-fold increase in two years. Once oil had been found, the main challenge was transportation to appropriate sites for refining; horsecarts, ships, trains, and pipelines all played a role starting in the early years of the industry.

During the industry’s first ten years, a large number of oil interests battled each other. Among them was John D. Rockefeller, who based his fortune on the control of refineries and railways rather than oil sources. Companies initially built refineries close to the sites of production. Within a few years, however, they were established in transportation hubs such as port cities. Cleveland, with the advantage of access to the Great Lakes, rapidly overtook Pennsylvania’s Titusville area in the volume of oil refined. Building on its long history as a port city, its emergence as a rail center, and its early transportation connections to western Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, soon caught up, initially as home to a large group of oil investors.

From the earliest days of the oil industry, Philadelphia developed into one of the major storage and refining sites for petroleum, constantly competing with other east coast oil ports, notably New York, but also Baltimore, Boston, and Portland, Maine. By the 1860s, Philadelphia as a city of more than 600,000 inhabitants was a major industrial site and port with a multitude of different manufacturers. As shippers, traders, and refiners inscribed petroleum flows into fixed infrastructures, they shaped a set of urban patterns in the city for decades to come. Located on the Schuylkill and Delaware Rivers, well connected by railways and some one hundred miles by river from the sea that connected it to Europe and the rest of the world, the city was a perfect location from which to export oil.

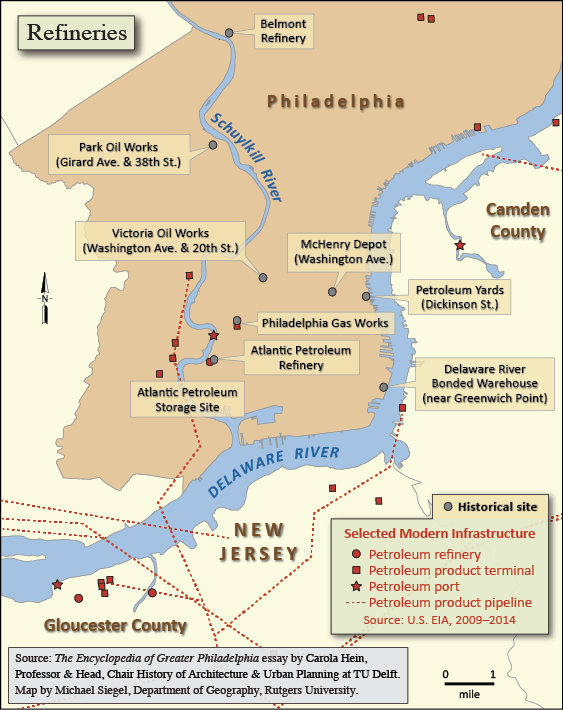

Positioning Refineries

The location of oil facilities within the city depended on a range of factors, importantly access to water, both for industrial processes and shipping. In the early years of the new industry, companies built oil storage sites and refineries in multiple locations throughout the city. By 1866 the city listed seven petroleum storage facilities and six refineries in several locations throughout the city. Several more appeared before 1875. Security issues became relevant after a range of disasters, which made the dangers of oil quickly evident. The Philadelphia Inquirer reported several incidents of refinery fires, big and small, with and without insurance, in the city or beyond its borders. After fire destroyed some of these facilities, affected companies sought more isolated locations at the urban periphery.

Environmental considerations became an additional reason for relocations, as was the case with the Belmont Petroleum Refinery, owned by Newhouse Nusbaum & Company. Located in an area that would become Fairmount Park, it was confined between the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad and the river, just above the Columbia Bridge where the Pennnsylvania Railroad split from the Junction Rail Road. This facility produced some 2 million gallons in 1868, but concerns mounted that its waste-water endangered the city’s water supply. As it was located on the Schuylkill River upstream from the Water Works, city officials feared for the quality of the drinking water. Together with other mills and industrial properties, the Belmont Refinery ultimately closed when the state failed to protect the city’s drinking water by buying up land for park purposes.

Despite such state action, the Schuylkill still was not safe from petroleum waste pollution after the Belmont refinery stopped operations. Refineries simply moved farther downstream and closer to the meeting point with the Delaware River, starting the growth of the industrial hub that subsequently defined the city’s southern boundary. In the late nineteenth century, a refinery cluster emerged on both sides of the Schuylkill, with one facility at Girard Point and the other at Point Breeze. Dating to 1866, Point Breeze initially refined lighting oil and subsequently became the oldest continuously operating petroleum facility in the world. A second petroleum center, later closed, emerged on the Delaware River at Greenwich Point, south of the existing port on the Philadelphia side.

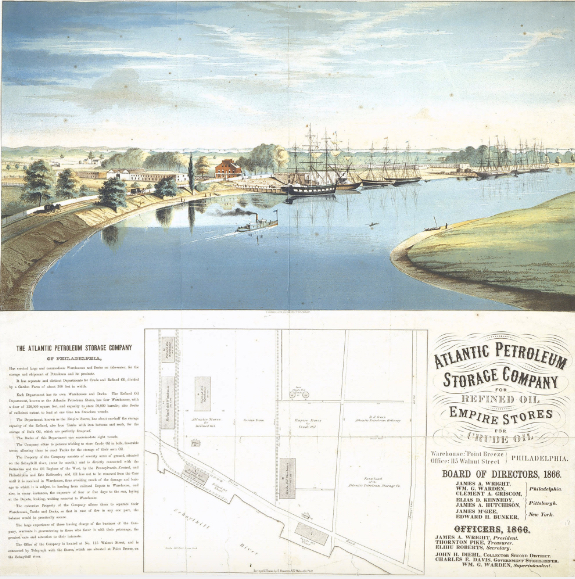

Many of the early refineries close to the Schuylkill and Delaware Rivers were built on agricultural land (though still within the city limits), making it easier to create industrial complexes and to run new railroads to them. By 1867, oil was so important in the city that the Philadelphia Inquirer asked whether petroleum had come to rival “King Cotton.” The Inquirer recognized the Atlantic Petroleum Storage Company as one major oil player. Established as a corporation in 1866, Atlantic was active in all the parts of the petroleum industry from drilling to refining and shipping. It occupied a seventy-acre property on the Schuylkill, offering eight hundred feet of wharf frontage “substantially finished” just below the Point Breeze Gasworks.

A Devastating Fire

In 1874, Standard Oil purchased the Atlantic company as part of its attempt to consolidate the oil transporting and refining business a single enterprise that was capable of weathering even major setbacks such as the destruction of its entire facility. This happened in 1879, when lightning destroyed the Atlantic Oil Refinery along with several ships that were moored on its wharves. Two thousand men lost their jobs and many of the seamen from the ships lost all of their belongings. The Standard Oil Company carried no insurance and had to pay for the reconstruction.

The interplay of oil ownership, transportation opportunities, and refining capacity made the early oil trade a complex business. Landowners and oil traders were not necessarily the same. The Pennsylvania Railroad’s oil interest in the early years extended beyond transport to the purchase of large plots of land in Philadelphia, notably on the Delaware at Greenwich Point, about 1¾ miles south of the Navy Yard. The Greenwich facility grew rapidly to bring together several oil companies in 1875. The Pennsylvania Railroad owned the land of the oil facilities on the Delaware, whereas independent producers controlled the oil business. Together they entered a price war over shipping rates that pitched them against Standard Oil and the Baltimore & Ohio, New York Central, and Erie Railroads. Ultimately, the PRR lost the contest and sold its own oil interests to Standard Oil. The Delaware facilities continued to work until 1911, then disappeared.

In the late nineteenth century the area experienced a major surge in the oil industry. By 1880, the Standard Oil Company controlled the refining of 90 to 95 percent of all oil in the United States, and the Atlantic Petroleum Company expanded its facilities. By 1891, 50 percent of the world’s illuminating fuel and 35 percent of all U.S. petroleum exports came from the 360-acre Atlantic refinery in Point Breeze that featured a navigable waterfront of 1.7 miles and 6 miles of private railroad track. The facility was burning 350,000 tons of coal each year to refine 40,000 barrels of petroleum daily, emphasizing a connection between Philadelphia as a center of coal transport and as a petroleum hub. As of 1907, petroleum products exported by the Atlantic Refining Co. accounted for 22 percent of the city’s export trade and were valued at $23,647,194 in foreign gold (surpassing cotton, which held 2.5 percent). Meanwhile a competitor had emerged in Philadelphia after 1901, as the region witnessed a second surge in the oil industry. Joseph Pew (1848-1912), co-founder of Sun Oil, built a refinery in Marcus Hook just outside Philadelphia in Delaware County for refining and resale of Texan crude that his company shipped on coastal tankers to avoid Rockefeller’s railroads.

The invention of gasoline-powered automobiles and their industrial production provoked new demand for petroleum as an engine lubricant and as fuel, prompting consumers and companies alike to push for further oil drilling. But as oil production and consumption increased and globalized, Philadelphia’s role as a major oil refiner decreased. Pennsylvania and New York had already reached a peak in production of 33,009,000 barrels in 1891. These states had already been overtaken by Russian production in 1888. The discovery of new oilfields in the United States, notably in Texas, between 1880 and 1905 had further reduced Pennsylvania’s prominence as a producer. The growing political and geopolitical importance of oil made it a major factor in colonialism, as European nations struggled to maintain their hold over the resource, and investment flowed outside the United States. As German submarines sank American oil ships during World War I, traffic along the Eastern seafront (including to Philadelphia) decreased and the United States promoted the construction of pipelines within and across the country in another major blow to the port. Over the next decades both the port and the oil industry in Philadelphia declined even further.

The end of Philadelphia’s role in the oil industry seemed close in 2011, as the price of imported crude oil rose and SUNOCO, formerly known as SUN oil, announced it would exit the refining business, threatening to close its struggling refineries on the Schuylkill River. Local and regional forces pushed to keep the plants open and maintain employment for its remaining 850 workers. The shale oil boom revived the financial viability of the refineries, as shale oil started to arrive by rail from North Dakota as no pipeline system was available. In 2012, SUNOCO entered a joint venture with the Carlyle Group under the PES name to update and expand the refineries.

Throughout the twentieth century, oil companies and states sought to transport oil from the production sites to the refineries and, ultimately, to the consumer. As inventors created new uses for petroleum products and as companies aggressively brought them to markets, oil became a dominant resource in daily life around the world. Because petroleum extraction sites were located far from sites of consumption, major oil companies expanded their distribution networks, built new shipping fleets, and established ports in Indonesia, Russia, the Middle East, and South America.

Throughout this process, as Philadelphia went from being a major oil exporter to being an importer, the city’s oil facilities on the Schuylkill continued to work: when production, distribution, and consumption patterns completely changed; when oil companies reinvented themselves with the emergence of the car as the main consumer of oil products; and as companies figured out how to produce a multitude of other products from oil. In the early twenty-first century, they even attracted oil business back into the city, exemplifying how oil logistics shape urban development, producing distinct spatial frameworks, infrastructure, land ownership patterns, and fixed production sites that linger well beyond their original function.

Carola Hein is Professor and Head, Chair History of Architecture and Urban Planning at Delft University of Technology, Delft, Netherlands. She has published widely on topics in contemporary and historical architectural and urban planning— notably in Europe and Japan. Among other major grants, she received a Guggenheim Fellowship to pursue research on The Global Architecture of Oil and an Alexander von Humboldt fellowship to investigate large-scale urban transformation in Hamburg in international context between 1842 and 2008. Her current research interests include transmission of architectural and urban ideas along international networks, focusing specifically on port cities and the global architecture of oil. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Pennsylvania derailment puts spotlight on increase in crude-oil spills (WHYY, February 16, 2014)

- EPA calls for measuring benzene, other things wafting over from refineries (WHYY, May 16, 2014)

- From oil drilling to oil painting – revitalization through Oil City’s artist relocation program (WHYY, August 4, 2014)

- Philadelphia refinery capitalizes on the shale boom (NewsWorks, September 29, 2014)

- Fire at South Philly refinery causes black smoke to rise (WHYY, January 10, 2015)

- PES oil refinery to close after fire (Associated Press via WHYY, June 26, 2019)

Links

- Striking Oil (ExplorePAhistory.com)

- A Petaled Rose Of Hell: Refineries, Fire Risk, And The New Geography Of Oil In Philadelphia’s Tidewater (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (PA.gov)

- U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)

- Development of the Pennsylvania Oil Industry (American Chemical Society)