Street Vendors

By Stephen Nepa

Essay

From the colonial period to the present, street vendors have been integral yet contentious features of Greater Philadelphia’s economic landscape. Providing massive numbers of customers with food, clothing, and other goods while allowing many working people an occupational foothold in the region, vending also sparked controversies regarding taxes, regulation, public health, and uses of space.

The region’s earliest street vendors (or “hucksters”) congregated without regulation in streets and alleys close to Philadelphia’s waterfront. Although some vendors resided within the city, others journeyed to town by horseback or ferry from the countryside. Using carts, baskets, and buckets, they sold fruits, vegetables, seeds, dairy products, and meats to eager customers. Other popular wares included buckwheat cakes (a breakfast staple), South Jersey produce, oysters, and pepper pot soup. The soup, selling for pennies a bowl, became internationally famous. Many “pepper pot women” were free Blacks, with some, including Flora Calvil and Polly Haine, gaining recognition for their theatrical cries and elaborate costumes. To the south, at Wilmington, Delaware, vendors gathered at the heavily trafficked Brandywine Bridge in the 1700s to sell wheat and other grains grown in New Castle County and southeastern Pennsylvania.

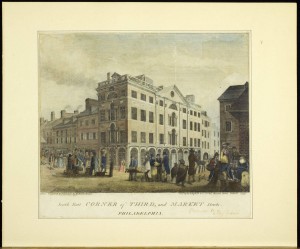

Lowly Status for Female Vendors

In Philadelphia, female hucksters sold poultry, nuts, and homespun goods in the High Street market stalls (the largest in the colonies) between Front and Fourth Streets, and vendors also found customers at stalls erected in Southwark (1745) and Northern Liberties (1763). Following the French Revolution (1789) and Haitian Revolution (1791-1804), which brought numerous goods and refugees to Philadelphia, vendors began selling French pastries and Creole items. “Exotic goods” were offered near the Willow Street Wharf, the city’s first “red light district.” The lowly status of both prostitutes and female vendors merged in public opinion to represent a shared ill repute.

After the American Revolution, Philadelphia merchants complained that street vendors destabilized prices and undercut profits. As a result, in 1789 the city imposed restrictions on public market space so that vendors could sell only in the market (and not on surrounding streets) during regular hours and could not offer merchandise purchased outside the city limits, which would create competition for licensed stalls or stores. While many vendors simply paid fines for violating the new rules, others moved locations, hid products from inspectors, or petitioned the city to lift the restrictions. After much protest, especially from female vendors who were poor, elderly, or disabled, the Pennsylvania Assembly in 1802 lifted the restrictions to allow vendors full access to Philadelphia’s markets. However, tensions between vendors and the city ebbed and flowed for many decades.

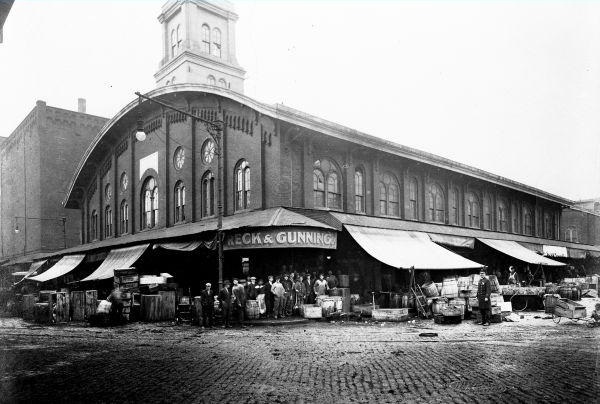

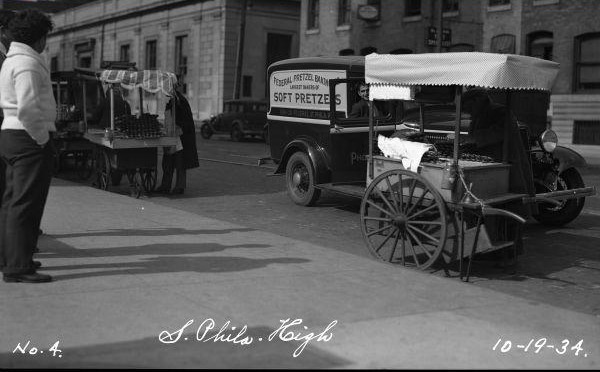

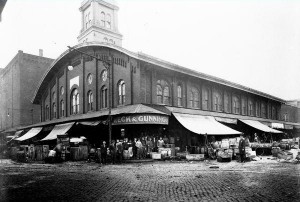

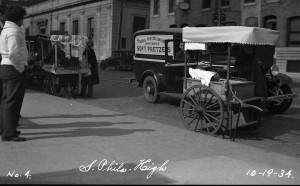

As the ethnic composition of the region diversified with immigration during the 1800s, many newcomers settling in ethnic neighborhoods in Philadelphia, Camden, and Wilmington found work hawking items from linens and bananas to jewelry and tea. Daniel Christopher Kleiss was credited as Philadelphia’s first street vendor of soft pretzels, which appeared around 1820. Other food vendors worked near the city’s Delaware (later Dock Street) Market, established in the 1850s. Dock Street remained a thriving yet overcrowded draw until its demolition in the 1950s. In Philadelphia’s Jewish Quarter along South Fourth Street (“Der Ferder” in Yiddish), vendors sold fabric, sewing supplies, and curtains from pushcarts. Vendors of “Jersey sausage,” a corn-fed pork variety made by Camden’s sausage weavers, sold their wares along that city’s Market Street well into the 1890s. The “hoagie” sandwich appeared in Philadelphia’s Little Italy and along Camden’s Benson Street in the late 1800s. In efforts to burnish vendors’ image, West Indian women who sold pastries in Center City dressed in crisp white uniforms.

“Curb Prices” vs. “Store Prices”

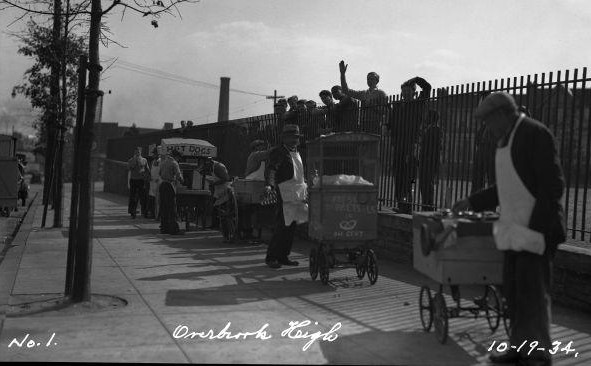

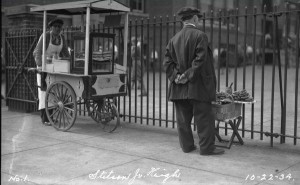

With restaurants and department stores growing in size and scope at the advent of the twentieth century, street vendors faced opposition from merchants, citizens, and elected officials over their cleanliness, legality of their presence, and quality of their merchandise. Merchants objected to differences between “curb prices” and “store prices” as vendors often undercut storefront businesses. Cities, including Trenton (1903) and Camden (1914), required licensing of all vendors as well as routine inspections of scales, merchandise, and cleanliness. Due to rising public health concerns, Philadelphia in 1922 required food vendors to cover their wares and store them at proper temperatures. Five years later, Building Inspection Bureau chief Morris Brooks (1888-1958) described vendors as “eyesores on our principal streets” and felt they gave Philadelphia a reputation as a city where customers could be easily swindled by larcenous sellers.

During the 1940s and 1950s, tensions over Philadelphia’s street vendors intensified. After a 1940 food poisoning epidemic was traced to a lunch cart in the city’s northeast, health director Dr. Hubley R. Owen (1883-1955) lobbied for firmer regulations. The following April, City Council required all food vendors to obtain licensing, cover their foods adequately, and adhere to strict rules of personal hygiene. Failure to comply resulted in fines between ten and fifty dollars. Vendors argued the restrictions harmed business, but the law proved difficult to enforce. Beginning in 1950, Fabric Row shop owners rallied against (and successfully banned) pushcarts. With Center City then undergoing renewal, police routinely cited or arrested vendors for health code violations, not displaying permits, or using vulgar language.

With many families decamping to suburbs and shopping malls through the 1960s and 1970s, African Americans and Asians increasingly made up the majority of Philadelphia’s street vendors. Along West Philadelphia’s Fifty-Second Street, West Indian and African vendors offered oils, batteries, and hair clips. Beginning in the mid-1960s, Korean vendors arrived in Philadelphia from New York and sold wigs, handbags, and accessories along North Fifth Street and in Upper Darby, Pennsylvania. On the campuses of Temple University and the University of Pennsylvania, vendors (many of them unlicensed) offered T-shirts, incense, jewelry, and fast food such as pizza, egg rolls, and hot dogs. In the 1970s, future Pennsylvania State Senator T. Milton Street (b.1941) and his brother John F. Street (b.1943), a future two-term Philadelphia mayor, sold hot dogs on Temple’s campus. Routinely harassed by police and inspectors, the brothers, reportedly the university’s first Black vendors, helped form the Black Street Vendors Association to legitimize their businesses. By the end of the decade, Temple constructed a permanent court to house roaming food vendors while allowing non-food vendors to remain on selected corners. At the University of Pennsylvania, where street vending had operated since the 1910s, codes of conduct and spatial limitations were imposed in the 1990s to better regulate the campus’s nearly 100 vendors.

During the 2000s, public markets such as Philadelphia’s Reading Terminal and Headhouse Square provided space for multiple vendors in one location. Food trucks also grew in popularity, often moored to college campuses from Newark, Delaware, and West Chester, Pennsylvania, to Glassboro, New Jersey, as well as urban squares in Wilmington and Philadelphia. Philadelphia in particular contained a vibrant food truck scene. In 2011, the New York-based Vendys held its first competition, naming Drexel University’s Cucina Zapata (tacos) and Sweet Box (desserts) best in the city. Other food trucks changed locations daily, alerting customers via social media. Despite firmer regulations, vendors still illicitly hawked T-shirts, scarves, and other items throughout Center City Philadelphia. With vendors outnumbering inspection agents, those operating illegally often did so without concern.

For centuries, the citizens and municipalities of Greater Philadelphia both appreciated and vilified street vendors. Despite fluctuations in regulations and enforcement, the continued presence of vendors and variety of their wares attested to their social and economic importance.

Stephen Nepa teaches history and American studies at Temple University, Rowan University, and Moore College of Art and Design. A contributor to numerous books and journals, he also appears in the documentary series Philadelphia: the Great Experiment and The Urban Trinity: The Story of Catholic Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Despite declining sales, Germantown street vendor says he has "the American dream" (WHYY, September 13, 2011)

- First meeting of new Philadelphia food truck vendors association (WHYY, December 12, 2011)

- Celebrate soup month with Philly's historic pepper pot soup (WHYY, January 26, 2012)

- Bringing out the best of Philadelphia street food (WHYY, July 30, 2012)

- Manayunk's StrEAT festivals draws thousands to Main Street (WHYY, April 13, 2015)

- Philly side hustle will be on full display during papal visit (WHYY, September 21, 2015)

- City, Aramark, other vendors at odds over 'Francis Festival' sales (WHYY, September 22, 2015)

- L&I apologizes to Temple food trucks, will work with vendors on overnight plan (Billy Penn via WHYY, April 24, 2019)

- Food cart owners say City Hall is pushing them out of Philly (WHYY, October 24, 2019)