Education and Opportunity

Essay

In the twentieth century, many urban school districts, which had been among the finest in the nation, became some of the most challenged. The Greater Philadelphia region reflected this trend. In 1900 the region’s school systems consisted of largely uncoordinated public, parochial, and private schools. Between 1900 and 1965 politicians, educational administrators, and civic leaders trained in the tenets of scientific administration worked tirelessly to centralize control and expand access so that families in Philadelphia’s outlying districts (which included West Philadelphia and Germantown), suburban communities, and rural outposts could attend modern primary and secondary schools. While reorganization led to new educational opportunities, these changes simultaneously increased educational inequality among the region’s youth because only some had access to its finest schools.

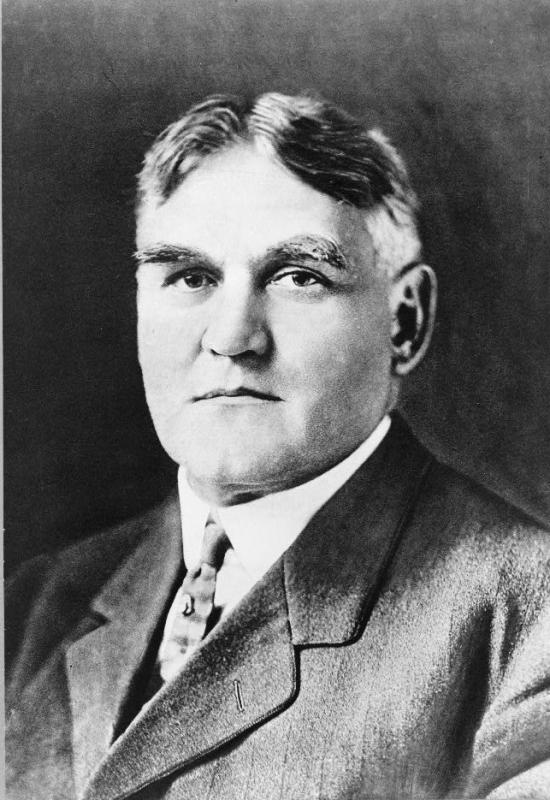

Before Pennsylvania state legislators passed the Reorganization Act of 1905 and Martin G. Brumbaugh (1862-1930) became Philadelphia’s school superintendent in 1906, corrupt budgetary and hiring practices plagued the School District of Philadelphia. Under Brumbaugh’s guidance, the board of education replaced its ward-based governance system with one that gave the superintendent the power to systematize and standardize the public schools. As superintendent, Brumbaugh obtained public funds to build additional primary and secondary schools, reform academic programs in the high schools, and raise teacher salaries. These policies increased access to educational institutions for Philadelphia youth, particularly those living in West Philadelphia, Frankford, and Germantown—beyond the city’s core—and alleviated overcrowding and part-time attendance patterns in the city’s primary schools. At the same time, the Archdiocese of Philadelphia expanded its school system to attract families who wanted their children to attend Catholic schools. These policies increased racial segregation in the city’s schools as white ethnics—primarily Italians and Irish—enrolled their children in parochial schools. African American families never enjoyed the same educational opportunities. For decades, the School District of Philadelphia maintained specific policies and informal practices that segregated Black and white youth and discriminated against Black teachers. African American leaders and concerned residents challenged these racist practices by forming grassroots organizations, such as the Educational Equality League, and mounting fundraising campaigns through the city’s Black newspaper, the Philadelphia Tribune.

The Great Depression brought new challenges to Philadelphia and suburban communities. As men and women lost their jobs and homes, the tax revenues for education plummeted. The School District of Philadelphia had faced fiscal difficulties before, but the Great Depression brought unprecedented challenges. To reduce costs, the board of education eliminated positions, cut salaries, and slashed programs.

During the 1930s, the region’s schools, like others in the nation, witnessed a dramatic increase in student enrollment. The Great Depression decimated the nation’s labor market, forcing thousands of working-class youth to enroll in school. As economic conditions worsened, some of Philadelphia’s upper class families had to transfer their children to the local public schools because they could no longer afford the tuition charged by private schools. As a result, students poured into public schools in the city and surrounding communities, creating overcrowded classrooms and underfunded schools. Both educational opportunity and inequality increased simultaneously.

World War II boost

World War II brought Philadelphia’s economy back to life—at least temporarily. The School District of Philadelphia created accelerated secondary school programs so that students could earn their diplomas before enlisting in the nation’s armed services or securing employment in a variety of wartime industries. As families moved to the region to find work and as youth returned to the labor market, student enrollment decreased at the secondary level even as it increased in elementary schools. The School District of Philadelphia did not have the budget or the resources to build new schools during the war, and thus primary school children, particularly African Americans, found that racial segregation in the region’s housing market barred them from the best schooling options.

When the war ended, Black leaders such as Floyd L. Logan (1901-78) and Cecil B. Moore (1915-79) urged local governments to provide Black children with greater access to educational opportunities by desegregating the region’s public schools. In the postwar period, boroughs and townships on the edge of Philadelphia and Camden expanded as GIs returned from duty and used their benefits to purchase suburban homes for their young families. Communities such as Levittown, Pennsylvania, were transformed from rural outposts to planned neighborhoods. These suburban communities provided young families with many advantages—sprawling landscapes, new schools, and modern shopping centers. But real estate agents and local homeowners routinely refused to sell homes to Black buyers and thus created suburban communities that were reserved almost exclusively for white upper- and middle-class residents.

As this suburban expansion and white flight from the city occurred, urban public schools systems like Philadelphia’s lost the tax revenues that white families had contributed. They also witnessed a dramatic increase in the number of Black youth in the public schools. This combination, coupled with the Philadelphia City Council’s failure to raise the revenues the schools actually needed, created an untenable situation. The school district could not hire enough teachers or build enough new schools. When they did find the land and money to build new schools, these new institutions often reinforced inequality by creating distinct schools for Black children in North Philadelphia and white children in predominately middle-class white communities such as Mount Airy and Overbrook. The school district’s policies and practices often left African American children in schools that were much more crowded than those attended by their white counterparts. School choice played a role, as well, as white Catholic families sent their children to parochial schools rather than their local public schools.

Desegregation Pressures

The pressure to desegregate mounted after the United States Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which stipulated that separate but equal educational institutions were unconstitutional. Civil rights activists in Philadelphia and suburbs like Abington, Pennsylvania, and Mount Holly, New Jersey, called for the desegregation of public schools. But those in charge of those schools routinely replied that the conditions were beyond their control. In 1959, Philadelphia’s Board of Public Education passed a resolution stating that the school district did not discriminate against anyone on the basis of race, color, religion, or national origin. Civil rights leaders pressed the board to do more, and in the mid-1960s, the school district finally admitted that Philadelphia’s public schools were indeed segregated. It commissioned several studies, such as the Report of the Special Committee on Nondiscrimination (sometimes referred to as the “Lewis Report” for the committee’s chairman, board Vice President Ada H. Lewis) whose findings the district’s leaders largely ignored. In 1967, Philadelphia youth staged a demonstration to urge the district to adopt Black history and a more Afrocentric curriculum. When Police Commissioner Frank Rizzo ordered his officers to use brutal force to quash this peaceful demonstration, it became more apparent than ever that equal educational opportunity was not a reality in Philadelphia.

In 1983, a commission convened by President Ronald Reagan issued A Nation at Risk, a report that emphasized the failures of the American educational system and ushered in a wave of local, state, and federal efforts to improve the nation’s schools. While it raised new concerns about the economic viability of American schoolchildren, the report did little to change the educational opportunities in the region despite the efforts of some civic leaders, concerned residents, and urban youth. Public schools in Philadelphia; Camden, New Jersey; and Wilmington, Delaware, still lagged behind their suburban counterparts with regard to per capita funding, academic achievement, and extracurricular activities. The racial segregation that had existed in the City of Brotherly Love since the beginning of the twentieth century had spread beyond Philadelphia. In 1997, Camden had a student population that was 57.7 percent Black and 38.1 percent Latino while most school systems in its adjoining suburbs were predominately white. The court-ordered reorganization of the public schools in Delaware’s New Castle County led to the creation in 1981 of four school districts that encompass Wilmington and its suburbs. The racial segregation in these school districts was not so blatant. For example, the Christina School District to the south was 33.4 percent Black and 4.2 percent Latino in 1997. The Red Clay School District to the north was 29.7 percent Black and 12.7 percent Latino.

In the first decades of the twenty-first century, some of these urban school systems welcomed charter management organizations in the hopes that market-driven solutions could alleviate inequities that had existed for decades. Educational opportunity is clearly greater today than it was at the beginning of the twentieth century, but along with these changes, the level of educational inequality has also increased, creating gross economic, political, and social inequities between youth who have access to first-rate educational institutions and those who do not.

Erika M. Kitzmiller is a historian of race, social inequality, and education who served as an assistant clinical professor at Drexel University and is currently the Caperton Fellow at Harvard University’s W.E.B. Du Bois Institute. She received her Ph.D. in History and Education and Master’s in Public Policy from the University of Pennsylvania and her B.A. from Wellesley College. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2014, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- In Camden, Marian Wright Edelman decries 'new American slavery' (WHYY, April 2, 2014)

- 'Election season' in North Philly: parents hear pitches on charter conversion (WHYY, April 16, 2014)

- Touring a North Philly Renaissance school, a microcosm of the city's education debate (WHYY, June 4, 2013)

- Philly Futures helps college-bound Northeast High student defy expectations, odds (WHYY, June 10, 2014)

- William Penn Foundation and Drexel University Partner to Improve Early Education in West Philly Promise Zone (NewsWorks, September 14, 2014)

- College Possible helping students be first in their family to attain higher ed (WHYY, November 20, 2014)

- Philly schools adopt five-year plan with minimal 'ask' of $30 million (WHYY, December 19, 2014)

- Nearly half of Camden's graduates get diplomas by appeal (WHYY, February 9, 2015)

- How is special education paid for in Pennsylvania public schools? (WHYY, April, 29, 2015)

- Philadelphia's universal pre-K commission begins work (WHYY, June 30, 2015)

- Rutgers-Camden to cover tuition for low-income students (WHYY, October 26, 2015)

- Area near Drexel in West Philly wins big school grant (WHYY, December 22, 2016)

- Philly approves one new charter school, rejects another two (WHYY, February 9, 2017)

Links

- Pennsylvania Education Directory/Maps (Pennsylvania Department of Education)

- List of Schools In New Jersey (New Jersey Department of Education)

- Delaware School and School Districts (Delaware Department of Education)

- School District of Philadelphia

- Central High School (PhilaPlace)

- Education in Philadelphia (ExplorePAHistory)

National History Day Resources

- Benjamin Rush, “A Plan for Establishing Public Schools in Pennsylvania,” from Essays, Literary, Moral, and Philosophical (Internet Archive)

- Benjamin Rush, "Thoughts Upon the Mode of Education Proper in a Republic," from Essays, Literary, Moral, and Philosophical (University of Chicago)

- Horace Mann, Lectures on Education (Internet Archive)

- Complaint in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 1951 (DocsTeach)

- Report of the Special Committee on Nondiscrimination of the Board of Public Education of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1964 (ERIC)

- A Nation At Risk, 1983 (HathiTrust Digital Library)