Canals

Essay

Canals transformed the economic and geographic scope of Greater Philadelphia in the first half of the nineteenth century. By providing a cheap and reliable mechanism for shipping goods, these complex technological systems funneled the products of broad hinterland regions to the Quaker City. Although canals delivered a wide variety of goods including farm products, lumber, and manufactured items, one commodity dominated the trade: anthracite coal. Brought to Philadelphia in prodigious quantities, anthracite coal powered much of the city’s industrial growth, helping a largely commercial city at the turn of the nineteenth century become the “Workshop of the World” by 1876. Ultimately eclipsed by railroads, canals were largely abandoned by the early twentieth century, but have been revived in recent decades as sites of tourism and heritage.

Throughout world history, cities have nearly always been established close to rivers to take advantage of their fresh water, ease of transport, and power for mills. Philadelphia was no exception. William Penn (1644-1718) founded the city near the meeting of the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers, thereby positioning Philadelphia to benefit from both waterways. In their natural state, the Delaware and Schuylkill allowed modest levels of lumber and farm products to be floated to Philadelphia when water levels were high (typically during the spring and fall) but only allowed goods to travel downstream above the falls in Trenton. As Philadelphia and its hinterlands expanded in population in the late eighteenth century, a number of politicians, merchants, and farmers sought a more reliable method of intraregional transport that would support larger boats and facilitate two-way traffic.

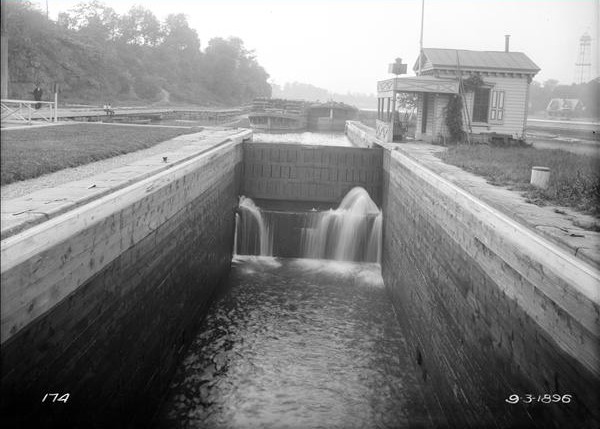

The incredibly challenging nature of building a canal, however, stymied most early efforts. Canals were not simply large ditches that could be dug and then filled with water. They were complex technological systems requiring locks and dams, underwater cements, storage reservoirs, and regular maintenance. When Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) led an effort in the late eighteenth century to improve the Schuylkill River, for example, his party was only able to remove a few troublesome rocks from the riverbed. Seven attempts to improve the Lehigh River failed before Josiah White (1781-1850) created a working system in 1820. Canals were among the most expensive and challenging endeavors of their day, and many of America’s first engineers learned their trade while struggling to tame waterways.

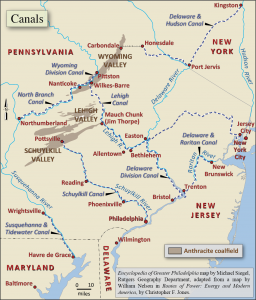

First Canal Took a Decade to Build

The dreams of Philadelphia’s canal boosters finally became reality in the 1820s. In 1815—the same time that New Yorkers began aggressively soliciting funding for the Erie Canal—the Pennsylvania Legislature granted a charter to the Schuylkill Navigation Company to build a canal system extending over one hundred miles from Philadelphia to Pottsville. Its directors ambitiously hoped to complete the first sections in a few years at a cost of $500,000, but ultimately ten years would pass before the canal was complete and the final price tag exceeded two million dollars. Without being bailed out in 1823 by Philadelphia’s richest citizen, Stephen Girard (1750-1831), the project likely would have failed. A more economical option was pursued on the Lehigh River, led by White, beginning in 1817. Because the enterprise was primarily oriented toward the downriver transport of coal, White set up a one-way transport network that opened in 1820 and cost less than $200,000 to build. Once the level of trade expanded, a full canal system allowing two-way traffic was built between 1827 and 1829 at a cost of approximately $700,000. Other important canals in the Greater Philadelphia region included the Delaware Division (built 1829-32), which complemented the Lehigh Canal in delivering goods to Philadelphia, as well as several canals that delivered anthracite coal to the New York Harbor, including the Delaware & Hudson (built 1825-28), Morris (built 1824-31), and Delaware & Raritan (built 1830-34).

Boosters imagined canals and engineers directed their construction, but the physical brawn and sweat of thousands of laborers transformed dreams into reality. Canal work was grueling and dangerous. Men taxed their bodies to pull up tree roots, dig trenches, blast stone ledges with dynamite, and reinforce banks. Often this work required them to move in and out of waist-deep water several times a day, thereby exacerbating their exposure to pathogens. As the historian Peter Way argues, the characteristics of canal labor were “strenuous, body-sapping work, crude, deleterious conditions, ubiquitous disease, the lurking spectre of death.” This work was performed predominantly by two groups: local farmers, who took short-term contracts to earn money during slow times in the agricultural cycle, and immigrant laborers, often Irish, who could not find other types of work. Canal work was known at the time, as Way observed, as the “roughest of rough work” and therefore was “performed by the lowest of the low.” When people had options, they rarely chose the back-breaking labor of digging canals.

Public versus private ownership loomed as a central question in canal construction during the 1820s and 1830s. The immediate financial success of New York’s Erie Canal (opened in 1825) led many to argue that Pennsylvania should sponsor canals to facilitate trade, promote the public good, and swell public coffers. Beginning in the late 1820s, Pennsylvania invested heavily in joint-stock companies authorized to create canals across the state and into the Ohio Valley, hoping the profits of these enterprises would buoy the state’s finances. Known collectively as the Public Works, in eastern Pennsylvania this included the Delaware Division canal, parts of the Main Line canal, and improvements to the Susquehanna River as well as the Philadelphia & Columbia Railroad, which traveled westward and served to connect Philadelphia with the state’s main canal network. Unfortunately, state ownership did not yield the dividends its proponents anticipated. Pennsylvania funded so many canal systems in the 1830s that the state acquired more than thirty million dollars of transportation debt by 1841 and ended up defaulting on its loans.

Anthracite Propelled Canals and Growth

Canals were built in many parts of the nation. The dominant role of anthracite coal as an article of trade—often 75 percent or more of the total traffic—distinguished the canals of Greater Philadelphia from their counterparts elsewhere. Rendered cheap by canals, flows of anthracite increased at an astonishing rate—from thousands of tons in the 1820s to several million tons annually by the Civil War. Due to this high volume of traffic, these canals typically earned higher rates of return than other canals. The Delaware Division, for example, was one of the few profitable lines in the Pennsylvania state canal system. Inexpensive and abundant coal, in turn, helped drive population and industrial growth in the Greater Philadelphia region. Burned to heat homes, power factories, propel steamships, and smelt iron, coal enabled Philadelphia to transform itself from a commercial city of merchants into an industrial powerhouse. By 1838, Philadelphia led the nation in the use of steam engines, and its industrial mix reflected the advantages provided by coal. Whereas New England textile manufacturers focused on activities enabled by water power—spinning and weaving textiles—historian Diane Lindstrom has shown that Philadelphia’s manufactures focused on processes where cheap heat was an advantage, including bleaching, dyeing, distilling, glassmaking, and metal-working. Canals, coal, and industrial Philadelphia grew together synergistically.

The region’s canals also spread the benefits of coal-powered industrialization to a thriving set of towns along their banks. Reading, Phoenixville, Bethlehem, and Allentown are examples of cities that experienced substantial growth due to the fact that canals could deliver raw materials to their factories and then ship manufactured products at low cost to seaboard markets.

Although canal builders were limited by nature’s arbitrary distribution of waterways for possible pathways, their choices over which canals to build—and which not to build—reflected human values and self-interests. Canals were competitive weapons, and Philadelphians favored those that connected the city with its hinterland regions. At the same time, they fought alternative projects that might benefit other metropoles. Many farmers in central Pennsylvania, for example, sought the development of a canal along the Susquehanna River that would allow them to easily ship their products to Baltimore. Believing that central Pennsylvania was part of the “natural” hinterland of Philadelphia, Quaker City merchants worked to block any development that might favor Baltimore merchants at their expense. They were not entirely successful, however. Canals such as the Delaware & Hudson directed coal away from Philadelphia and to New York City. Similarly, the Chesapeake & Delaware Canal (opened in 1829) funneled some of the region’s trade to Baltimore. Philadelphia grew its hinterland, therefore, by selective support of canal building.

Rail Dooms the Canals

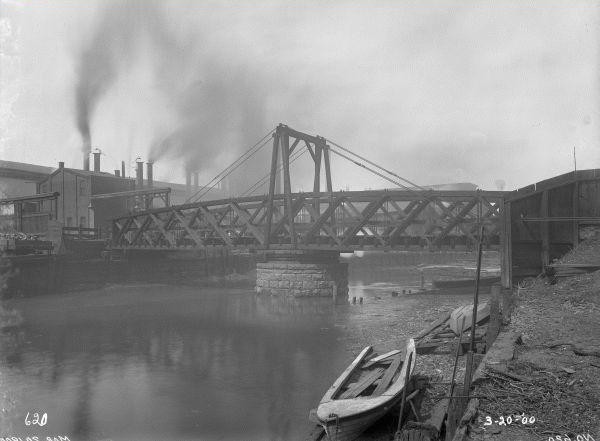

Beginning in the 1840s, canals faced competition from a new transport system: railroads. Canal and rail interests fought bitterly to gain superiority in the shipment of anthracite coal and other goods, with railroads such as the Reading (built 1833-42), Lehigh Valley (1846-55), and Delaware, Lackawanna, and Western (1849-51) ultimately prevailing by the last third of the nineteenth century. Although this shift in transport technology dramatically altered which organizations profited, its influence on the geography of the Greater Philadelphia region was not necessarily as profound. In many cases, railroads were built right next to canal paths, ensuring a similar geography to the flow of goods.

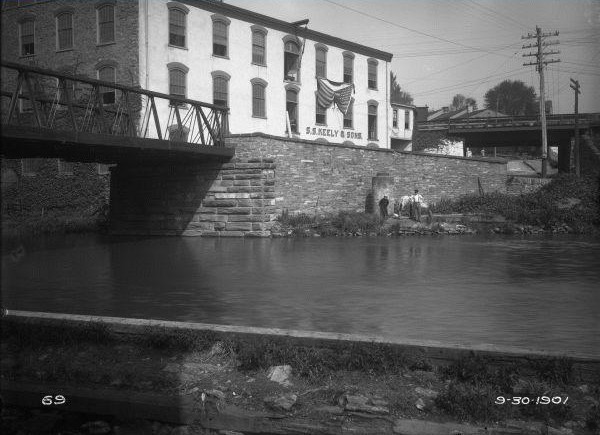

Canals began a slow decline in the 1870s. However, their eclipse took many decades, and several canal systems maintained operations into the post-World War I era. Even with railroads ascendant, canals often provided price competition that helped lower the cost of all transport services. In many cases, canals offered lower rates to shippers of coal and agricultural goods. Traffic on the Schuylkill Navigation largely dried up by the 1890s, the Delaware & Hudson Canal was drained in 1898, the Manayunk and Delaware & Raritan canals ceased operation by the mid-1930s, and the Lehigh Canal followed in the 1940s.

Beginning in the 1950s, several of the region’s canals were resuscitated as tourist sites and historical landmarks. Towpaths now serve as bucolic walking trails, and the canal waters and trees along the path provide harbor for many animals. Some old locks have been restored as sites of industrial heritage. For example, the Delaware Division Canal became the Roosevelt State Park in the 1950s (now known as the Delaware Canal State Park), several parts of the Delaware & Hudson Canal are now protected by the National Park Service, and some parts of the Lehigh Canal have been preserved starting in the late 1970s, including a section maintained by the National Canal Museum in Easton as part of the Delaware & Lehigh Heritage Corridor.

Overall, canals played an enormously influential role in shaping the relationships between Philadelphia and its hinterlands during the nineteenth century. Moreover, the legacies of these technologies remain. Even in the modern era of railroad and automobile transport, many of the region’s centers of population and industry can still be found in those places initially served by canals.

Christopher F. Jones is a historian of energy and environment with expertise in the mid-Atlantic region. His book, Routes of Power: Energy and Modern America (Harvard University Press, 2014), analyzes the causes and consequences of America’s first energy transitions, with a particular emphasis on the transport of energy in the Greater Philadelphia region. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History