U.S. Mint (Philadelphia)

Essay

Coins have been minted in Philadelphia as long as the federal government has produced legal tender coins. First authorized by Congress in 1792, the U.S. Mint’s Philadelphia facility (commonly known as the Philadelphia mint) in the early twenty-first century remained the nation’s largest producer of coins. Its history has been intertwined with the complicated history of the American currency system.

Following the Revolutionary War, virtually all coins circulating in the United States were foreign. Because these coins reflected several dissimilar coinage systems, they could be difficult to use in everyday transactions. To create a simple, uniquely American coinage system, Congress passed the Coinage Act in 1792. This groundbreaking piece of legislation authorized the creation of a mint to manufacture coins representing American denominations (dollars and cents). The site chosen for this mint was Philadelphia, then the capital of the United States.

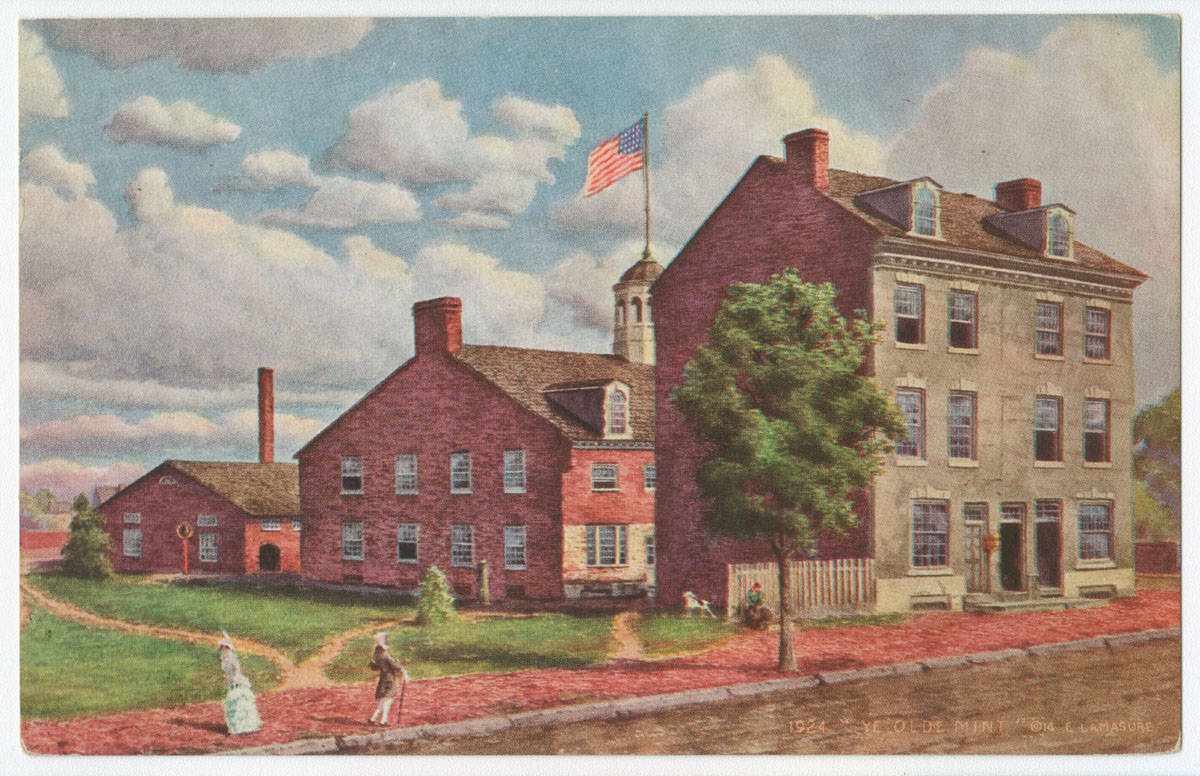

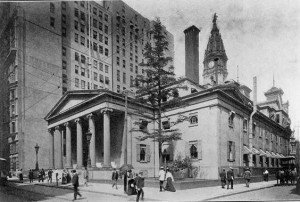

The first Philadelphia mint, founded in 1792, operated in a multibuilding facility on Seventh Street between Arch and Filbert Streets. Guarded by the newly established United States Mint Police, the first mint produced copper half-cent and one-cent pieces, silver half-dimes (the precursor to the modern nickel), dimes, quarters, half-dollars, and dollars, as well as gold two-and-a-half-dollar, five-dollar, and ten-dollar coins. However, because it was dependent upon the power of men and horses, the production of the nation’s first coins was slow and laborious. As the United States grew, the small, increasingly outdated mint could not keep up with the demand for coins. Consequently, in 1833 the mint moved to a new, larger building at Juniper and Chestnut Streets. In 1911, the last surviving building from the first Philadelphia mint facility was demolished.

Gold Rushes Spur Coin Production

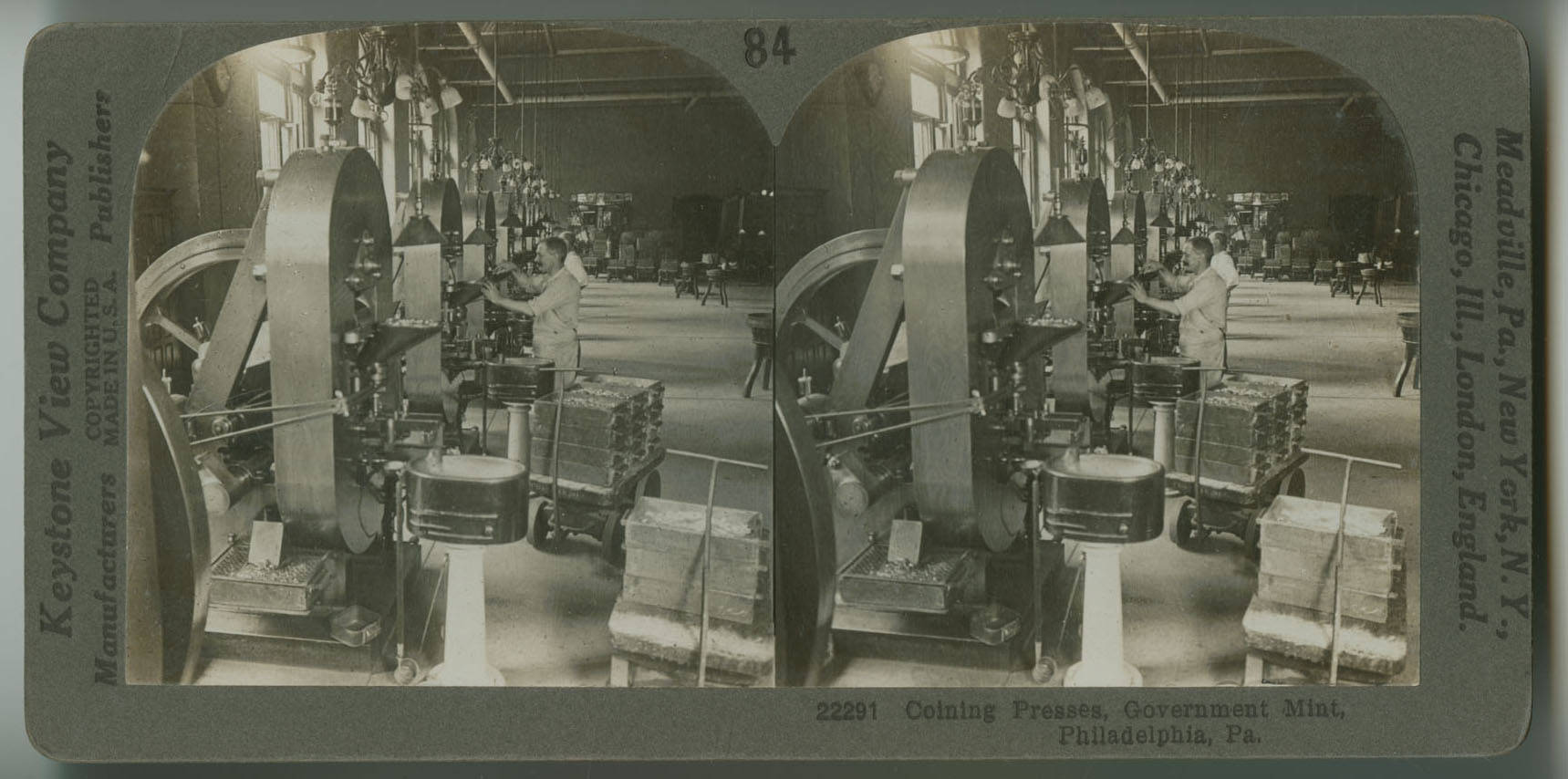

The second Philadelphia mint increased the output of coins with advanced metal-refining methods and state-of-the-art, steam-powered coin presses. Following gold rushes in North Carolina, Georgia, and California during the 1830s and 1840s, the Philadelphia mint converted vast quantities of newfound gold into millions of circulating gold coins. To alleviate frequent coin shortages, the second Philadelphia mint briefly produced several unusual denominations of coins, including bronze two-cent pieces, silver three-cent pieces, and gold three-dollar coins. To ease pressure on the Philadelphia mint and reduce transportation costs, the United States government established several other mints around the nation. Nonetheless, none of these satellite facilities surpassed the Philadelphia mint in terms of overall production.

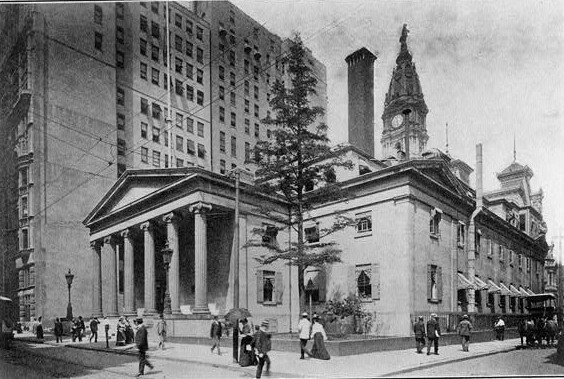

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, as the United States took its place as a global power, the Philadelphia mint began producing coins for other nations. Eventually, the Philadelphia mint struck coins for dozens of countries, including Panama, the Philippines, and Cuba. However, the size of the second Philadelphia mint’s facility hindered its production capabilities. To increase output and improve efficiency, the mint moved in 1901 to an even larger facility at 1700 Spring Garden Street. The building that housed the second Philadelphia mint was demolished shortly after being sold in 1902.

Located near the United States Smelting Company, several machine shops, and Reading Railroad tracks, the third Philadelphia mint had an ideal location for receiving raw supplies and transporting finished coins. The massive building occupied nearly a full city block. Because of its generous size and well-chosen location, the third Philadelphia mint quickly became one of the most productive coin manufacturing facilities in the world. The highly productive mint responded to the fluctuating demands of the American economy, ensuring that the nation’s coin supply remained plentiful.

During this period, external political changes altered the metal compositions of the coins produced by the Philadelphia mint. In 1933, the mint ceased production of circulating gold pieces when the federal government abandoned the gold standard. Thus, U.S. paper currency could no longer be exchanged for gold coins or bullion. During the Second World War, the mint contributed to the war effort by producing coins with reduced quantities of nickel and copper (metals vital to the production of arms and munitions), including the famous 1943 steel penny. At the end of 1964, the mint ended the production of circulating silver coins as the federal government went off the silver standard. As a result, “silver certificates,” the United States’ circulating paper money, could no longer be cashed in for their value in silver and silver-based coins became collectors’ items.

Despite the impressive productivity of the third Philadelphia mint, over time its equipment became outdated and its production processes grew increasingly inefficient. In an effort to improve overall efficiency, in 1969 the Philadelphia mint moved once again to a larger, more technologically sophisticated facility on Independence Mall. After the opening of the fourth mint, the building that once housed the third mint was acquired by Community College of Philadelphia, becoming part of the college’s main campus.

Since opening its doors in 1969, the fourth Philadelphia mint has been the United States’ premiere producer of circulating coins. Beginning in the 1980s, the mint diversified its output by producing collectable bullion and commemorative coins and medals. One of the most productive manufacturing facilities in the city, the Philadelphia mint proved capable of producing more than one million coins within a twenty-four hour period. Identified easily by a “P” mintmark or, in the case of pennies and older coins, the absence of a mintmark, coins manufactured at the Philadelphia mint have been among the most readily available in the United States. Evidence of the Philadelphia mint’s impact on the nation’s money supply can be can be found in pockets, piggy banks, and cash drawers throughout the country.

Stephen Burciaga received an A.S.B. in Culinary Arts and Restaurant Management from the Pennsylvania School of Culinary Arts, a B.A. in History from York College of Pennsylvania, and an M.A. in History from Millersville University of Pennsylvania. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History