Law and Lawyers

Essay

From its earliest days as an English colony, Pennsylvania needed lawyers to run the government, settle disputes, and keep the peace. As Philadelphia became a large city and important commercial, insurance, banking, and shipping center on the eve of the American Revolution, its lawyers were crucial to every civic endeavor, including the making of a new nation. With the dawning of the Industrial Revolution and the birth of corporations, Philadelphia’s lawyers kept pace, growing from one-man practices to giant law firms. The law evolved as the country grew up and opportunities for Jews, women, and African Americans expanded in the legal profession and judiciary throughout the twentieth century.

When William Penn arrived in 1682 to govern as the proprietor of Pennsylvania, he brought with him a largely English system of government and law. This included counties, governing councils, courts, jails, judges, sheriffs, constables, and justices of the peace. The same legal system was brought to New York and New Jersey and the three lower counties of Penn’s grant that later became the state of Delaware.

Like so many other aspects of colonial life, Penn’s followers, the Society of Friends, or Quakers, put their own stamp on the early provincial Pennsylvania legal system as well as the governments and law of West and East Jersey. Although he had trained as a lawyer for a year in London, Penn and his Quaker brethren mistrusted lawyers and the unwritten and vague English common law, interpreted solely by judges, under which the Quakers were persecuted for their beliefs.

Quakers believed in a gentler form of criminal justice. They preferred fines and public shaming to imprisonment and capital punishment, and they favored informal arbitration of civil matters among themselves and disdained lawyers. Nevertheless, English-trained lawyers came to Pennsylvania and made themselves useful to the new colony, becoming civic leaders and holding public office. In the earliest days, judges were likely to have little or no formal training and were chosen more for their character and stature in the community than their legal knowledge. Very few lawyers involved themselves in criminal matters, as it was the custom for the accused to represent themselves in court even in capital cases, trusting their fate to juries of their neighbors.

London for Legal Training

The earliest colonial lawyers specialized in civil practice stemming from land disputes, debt, and trade. They either trained at one of the four Inns of Court, prototype English law schools, in London before immigrating to America or went back there for training. Sending a son back to England for legal training was an expensive proposition, so in most cases students apprenticed to experienced local lawyers for periods of several years, commonly paying their mentors fees for the privilege. Students learned the law from sitting in court and watching proceedings and from copying legal documents. Both judges and lawyers “rode the circuit” to outlying counties that lacked their own courts to conduct hearings and trials.

As Anglican immigrants, as well as Germans, Dutch, Swedes, and other Europeans began to outnumber Quakers in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, they gradually dropped out of civic affairs, finding that many aspects of governance clashed with their religious beliefs. Thus, English common law became the prevailing standard in the middle colonies. Lawyers largely depended on a handful of treatises on legal procedure, Blackstone’s “Commentaries on the Laws,” and their knowledge of the English common law to conduct the legal business of the colonies. However, as the colonies developed their own legal systems, their legislatures undertook to codify the laws, and these new legal codes required trained lawyers and judges to apply and interpret them. The courts and bar associations gradually established standards for lawyers and restricted access to the courts to lawyers who met those standards. By the 1760s, lawyers were required to complete a four-year apprenticeship with “some gentleman of the law” before they were allowed to practice in the county courts and a year of such practice before they could appear before the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. Law books were scarce, and it was often a significant part of an apprentice’s work to copy those borrowed from other lawyers

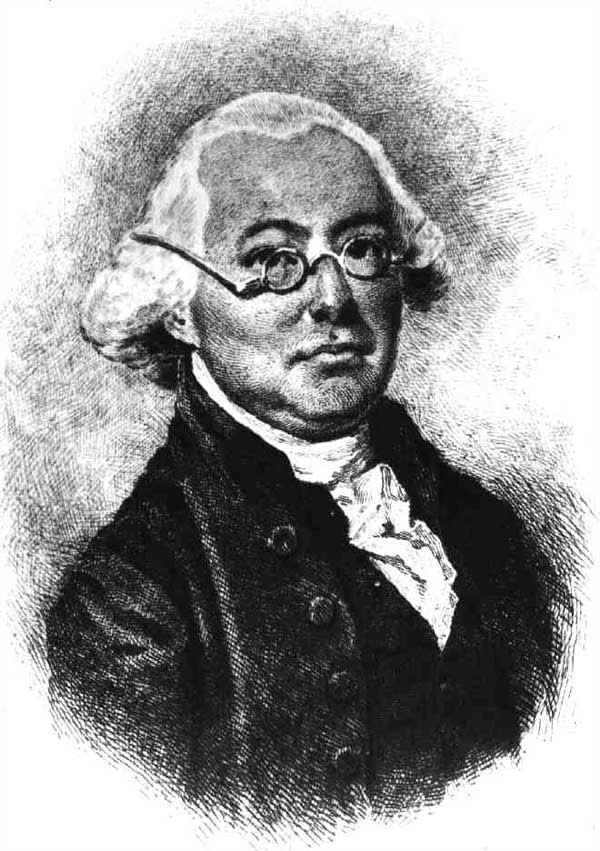

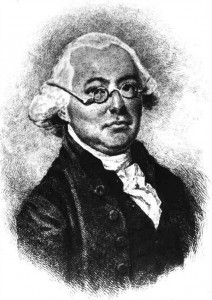

By the Revolutionary War, Philadelphia had a thriving legal fraternity, and many of the colony’s lawyers played prominent roles both in resisting and in forging the new nation. Philadelphia’s conservative, upper-class attorneys largely supported the crown and opposed the movement toward independence, but some became revolutionaries. One, James Wilson (1742-98), a Scottish immigrant who settled in Philadelphia, was a signer of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution and served as one of the first associate justices of the U.S. Supreme Court.

After the war, Philadelphia was the second-largest city in the new country and was a center of manufacturing, shipping, insurance, and finance. From 1790 to 1800 it was also the national capital. The national and state governments and all of the city’s courts were located on Statehouse Square at Chestnut Street between Fifth and Sixth Streets. Lawyers lived and worked in the same area and congregated daily in the surrounding streets. They were a small group, well known to one another, and many were members of Philadelphia’s oldest and wealthiest families. Judges and lawyers kept up the English custom of powdered wigs and formal black attire for some years after the war. Throughout much of the nineteenth century the city’s lawyers carried distinctive green cloth bags in which they transported their legal papers so that “green bag of technicalities” became a pejorative for lawyer.

Single Practitioners Dominated

A typical law office of the time was a two-story residence with the ground floor dedicated to offices and the second floor serving as family quarters. Most lawyers were single practitioners or formed firms when their sons or other relatives followed them into the profession, and partnerships were rare until the late nineteenth century. Around 1800, a partnership was usually two individuals: one man, the barrister, to appear in court and the other, the solicitor, to conduct business transactions. By the end of the century, one-man offices and two-man partnerships had evolved into hundreds of larger law firms. After the war, the law courts became distinctly defined as criminal, civil, and chancery, or business, courts. In Pennsylvania, lawyers did a good business litigating shipping and insurance issues stemming from the piracy of cargo ships in a separate maritime court. Each county had its own trial court called the Court of Common Pleas, while the Supreme Court and Superior Court became exclusively appellate institutions. Lawyers either settled in each county seat or migrated there from Philadelphia to practice law. In Delaware County, when the county seat moved from Chester City to Media in 1850, dozens of attorneys relocated to the new town as well.

The education of lawyers in the new nation continued as before, with lengthy apprenticeships, but students no longer went to the Inns of Court for training. American universities, such as Harvard, Yale, and Columbia, began to teach law courses as well. James Wilson launched a promising series of lectures in 1790 at the College of Philadelphia, later to become the University of Pennsylvania, but he lectured for less than one term before giving up his academic endeavors.

Another early development was that printers began publishing court decisions and legal codes, creating the need for lawyers to amass law libraries. In 1802, seventy-one attorneys formed the Law Library Company of Philadelphia to share access to law books. The law library was a stock company whose shares were valued at $20 and whose members paid annual dues of two dollars. In 1821, sixty-seven Philadelphia lawyers formed the first American bar association, the Law Association of Philadelphia, which merged with the law library in 1827. The bar association split from the law library in 1967 and the library became the Jenkins Law Library, still a major resource for Philadelphia-area lawyers.

Tarnished Reputation

In the Jacksonian era, the public generally looked down on the legal profession. Many lawyers had tarnished their reputations in the post-war years with land speculation and financial wheeler dealing. Some of Philadelphia’s attorneys got caught up in these practices, but the legal community persevered because the city’s thriving business and commercial activities needed well-trained lawyers.

The University of Pennsylvania established a law department in 1850 and thereafter, requirements for admission to the bar included university training. Philadelphia attorney Henry E. Wallace founded The Legal Intelligencer in 1843, making it the nation’s oldest continually published legal newspaper. It published legal news, opinions, legal notices, and insider gossip on the activities of lawyers and law firms. Even though Philadelphia Quakers were prominent leaders of the pre-Civil War abolition movement, the city’s lawyers, still largely upper class and conservative, were unsympathetic to the abolition cause. Nevertheless, a handful of Philadelphia lawyers became involved in the antislavery movement prior to the war, and many law students and attorneys fought on the Union side.

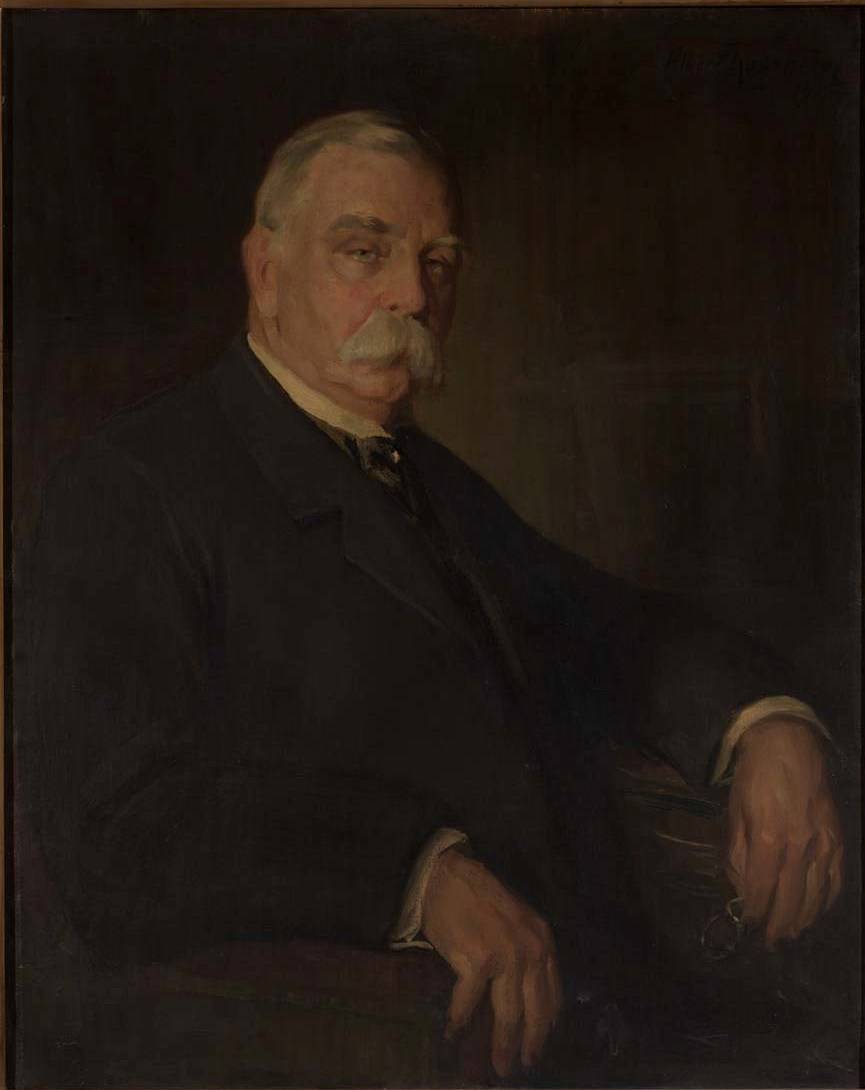

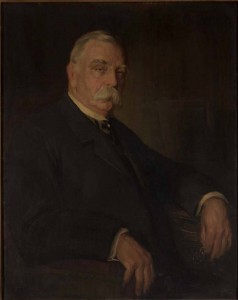

Private John Graver Johnson (1841-1917) emerged from the war to become the most celebrated Philadelphia attorney of the nineteenth century. Even though he was a single practitioner and a product of the apprenticeship system, Johnson was considered the most skilled corporation lawyer in the United States of the century. He represented the Sugar Trust in the 1880s in one of the first antitrust cases after the adoption of Sherman Antitrust Act. Over the next 35 years, he represented countless banks and corporations, including U.S. Steel Corp., and argued numerous times before the U.S. Supreme Court. Johnson also amassed a valuable art collection that he left to the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

The city expanded geographically throughout the nineteenth century, and as its lawyers prospered they began to move their residences, along with the merchants, physicians, and captains of industry, to the Rittenhouse Square area around Nineteenth and Chestnut Streets. At the same time, immigrants poured into Pennsylvania and the legal profession began to open up slightly to Irish and Italian Catholics, Jews, Black people and women—the children of farmers, laborers, and small business owners.

The Move to City Hall

In 1901 Philadelphia City Hall was completed at Broad and Market Streets and the courts, the bar association, and the law library all moved out of the State House Square complex and into the massive new building. At the same time, elevators and cast iron construction materials allowed for the proliferation of tall office buildings, including the sixteen-story office Land Title Building, constructed at Broad and Chestnut Streets, across from city hall. Lawyers rented offices and established firms of various sizes in the new buildings. The invention of the typewriter and telephone revolutionized how law firms and businesses conducted their affairs.

A handful of Jewish lawyers practiced law in Philadelphia throughout the nineteenth century, from about 1800, but they were not welcome in the upper-class Protestant circles of the Philadelphia legal community or invited to join gentile law firms. Horace Stern (1878-1969) graduated from the University of Pennsylvania Law School in 1899 and formed a partnership with Morris Wolf in 1903 to create one of the first all-Jewish Philadelphia law firms, Wolf, Block, Schorr & Solis-Cohen. Stern left the firm to take a seat on the Philadelphia Court of Common Pleas in 1920 and became chief justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court in 1952. Wolf, Block hired and nurtured countless Jewish lawyers, becoming one of the largest law firms in the United States before its dissolution in 2009.

Since African Americans had little economic or social power throughout the nineteenth and much of twentieth centuries, the city’s small number of Black lawyers were excluded from the white legal community and found work practicing criminal law and handling legal matters within their own community. In the first half of the twentieth century, Black lawyers educated in Philadelphia went to practice law in the minority communities in other counties of the state or were able to gain employment in community and government agencies. Many gravitated to legal work for churches, municipal legal departments, and organizations, such as the NAACP and the National Bar Association, formerly the Negro Bar Association, that advocated for fair housing and employment, school integration, criminal justice reform, and other issues that later coalesced into the Civil Rights movement. The Negro Bar Association was founded in 1925 after five African American lawyers were denied admission to the American Bar Association. By the 1940s it had established free legal clinics in most U.S. cities with more than 1,500 Black residents, including Philadelphia.

African American Lawyers Ascend

Two African Americans, Henry Johnson and Isaac Parvis, were listed in the 1850 Philadelphia census as lawyers, but nothing else is recorded about them. Theophilus J. Minton was admitted to the bar in 1887. Aaron Mossell Jr. (1863-1951) was the first Black student to graduate from the University of Pennsylvania Law School, in 1888. His daughter, Sadie Mossell Alexander (1898-1989) was the first African American woman to graduate from Penn Law School, in 1927, after having already become the first Black woman to earn a Ph.D. in economics, also from Penn. She practiced law until 1982. Her husband, Raymond Pace Alexander (1898-1974), a graduate of Harvard Law School, formed the first Black law firm in Philadelphia and, in 1959, was elected the first Black judge of the Philadelphia Common Pleas Court. Both were very active in the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

Women in particular had a very hard time being taken seriously by the legal profession. Caroline Burnham Kilgore (1838-1909), a medical doctor, fought for next ten years to gain admission to the University of Pennsylvania Law School, finally graduating in 1883. She was admitted to practice before the Pennsylvania Supreme Court two years later and before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1890. Even after women lawyers became more common, they often practiced law in their husbands’ firms or were relegated to probating wills and handling domestic relations cases, areas of law seen as suitable for women.

Several new legal specialties developed over the span of the twentieth century, including tax law, bankruptcy, personal injury, labor and employment, intellectual property, consumer fraud, and environmental law. When men and women were injured or killed on the job or in auto accidents, lawyers would seek to represent them or their families for a contingency fee, payable as a percentage of whatever recovery the client received. The legal establishment frowned on this “ambulance chasing,” but in 1928 the Philadelphia Bar Association concluded that the contingency-fee arrangement was necessary for the protection of injured persons who did not have the resources to pay attorneys up front.

Night School at Temple University

Admission to the bar required graduation from law school and passage of a rigorous bar examination. The apprenticeship path had disappeared by the end of the nineteenth century, but another pathway opened, night law school. Temple Law School opened in 1895 as an evening school, enrolling 46 students in its first class and graduating 16 of those students in 1901. Night school enabled working class Irish, Italians, Jews, Black people, and women to attend classes while they were also holding down day jobs. Lawyers educated at Penn looked down on Temple’s evening law school graduates as being less well educated and holding less prestigious degrees, and Temple was seen as being “the Jewish law school.” It was thus nearly impossible for Temple graduates to break into the large old-family firms.

The legal profession in Philadelphia, as in other cities, became a distinctly two-tiered system with the upper-class Protestant “governing class” lawyers operating quietly from plush offices to serve their political and corporate clients, while night school graduates became single practitioners or formed small partnerships, operating from storefront offices, representing the working class, minorities, and immigrants. Philadelphia’s first Legal Aid Society office opened in 1901 to serve the poor. By 1932, in the depths of the Great Depression, it was averaging 15,000 cases a year. Starting around 1900 courts throughout the country also started to set up public defenders offices or adopted a system of appointing lawyers from private firms to represent indigent criminal suspects.

In 1908, the American Bar Association published the first Canon of Professional Ethics for practicing attorneys. One of those canons was a requirement that wealthy law firms provide a significant amount of work pro bono publico, or for the public good, representing poor clients, a requirement still in effect. In addition, area law schools also have provided pro bono programs to both serve the poor or specific causes and to provide practice for students.

After World War II, the G.I. Bill of Rights provided veterans with stipends and tuition to go to college, making college education available to millions. Penn and Temple law schools had no available space and had long waiting lists, but other area law schools, Rutgers University Law School in Camden, New Jersey, Villanova University Law School in Montgomery County, and Widener School of Law in Delaware helped take up the overflow.

The Civil Rights Movement

Many Black Philadelphia attorneys, long on the forefront of the fight for social justice, became involved in the 1960s civil rights movement. As counsel for the NAACP, Raymond Pace Alexander led legal battles to desegregate Pennsylvania schools as early as the 1930s. World War II Marine veteran Cecil B. Moore (1915-1979), a Temple graduate admitted to the bar in 1953, took the fight to integrate Girard College, a school established in the previous century for orphaned white boys, to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1965 and won. Even as late as the 1960s, women and Black individuals still struggled for equality in the Philadelphia legal community. There were few (or no) Blacks or women on the bench, in big firms, or in executive positions in large corporations. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 made minorities and women a protected group in education and employment, and by the 1970s, women accounted for nearly 50 percent of area law students, while Black male enrollment increased but remains low in proportion to Black representation in the general population. Also by the 1970s, the Philadelphia area’s major industries— locomotive- and shipbuilding, auto making, steel production, pharmaceuticals, and textile manufacturing— began to decline or relocate to other parts of the country, taking with them many legal jobs. When the Pennsylvania Railroad went bankrupt in 1970, it was the largest bankruptcy in American history and several hundred attorneys worked on its dissolution for years.

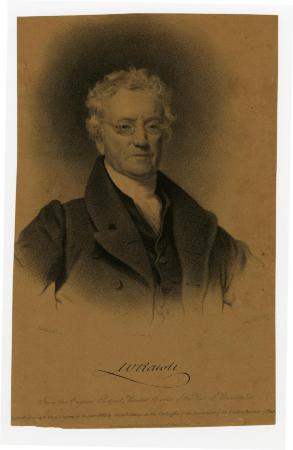

In the last half of the twentieth century, many law firms grew to include hundreds of lawyers and multiple offices. Inevitably such growth included expansion to other cities and countries, either through mergers or the creation of branch offices. Tracing its origins back to 1875, Philadelphia’s Dechert, Price & Rhodes, as it came to be known in 1962, opened offices in London and Brussels, among other global cities, even as it established offices in Washington and New York before opening other offices in the region: in Harrisburg (1969) and Princeton (1987). Another venerable Philadelphia firm, Ballard Spahr, dating to 1885, opened its first branch office, in Washington, D.C., in 1978, later expanding services to New Jersey in 1999 and Delaware in 2002. Because most U.S. corporations incorporate in Delaware and the state’s chancery court has dictated corporate governance for companies throughout the country, Ballard was but one of dozens of large firms that located in Wilmington. One prominent Philadelphia firm, Pepper Hamilton, relocated to Berwyn in Philadelphia’s western suburbs. A few firms first established on the other side of the Delaware, in Camden, left their urban locations as well. These included both Archer and Greiner and Brown Connery, both founded in Camden in 1928. Well after they established their presence in the South Jersey suburbs in the 1970s, both firms opened offices in Philadelphia, affirming the continuing importance of a location central to the region. While some old established firms became less relevant and downsized, merged, or faded away, the nation’s oldest continuously functioning law office, Rawle & Henderson, founded in Philadelphia by William Rawle in 1783, was still flourishing in 2015 with offices in five states.

By the end of the twentieth century, technological innovations continued to change the practice of law and business in general. Copy machines, faxes, computers, email, and the Internet all revolutionized the practice of law, greatly improving the productivity of courts, law firms, and business. The legal documents once produced by quill pens in candle-lit front parlors 300 years ago are now filed and shared electronically with the stroke of a key.

Jodine Mayberry is a retired journalist. She was a legal writer and editor for West Publications, a division of Thomson Reuters, for 18 years. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Big Philadelphia law firm sends financial "SWAT Team" to Reading (NewsWorks, August 18, 2011)

- A sign of change for Philadelphia: the first female chair at the Morgan Lewis law firm! (WHYY, October 2, 2013)

- Trial Lawyer Hall of Fame now in order on Temple campus (WHYY, September 10, 2014)

- Nelson Diaz talks surfing in Puerto Rico, attending Temple Law School, and why education matters (NewsWorks, May 1, 2015)

- Influential law representing children approaches milestone anniversary (WHYY, September 4, 2015)

- Philly DA Seth Williams pleads guilty, resigns (WHYY, June 29, 2017)