Lafayette’s Tour

Essay

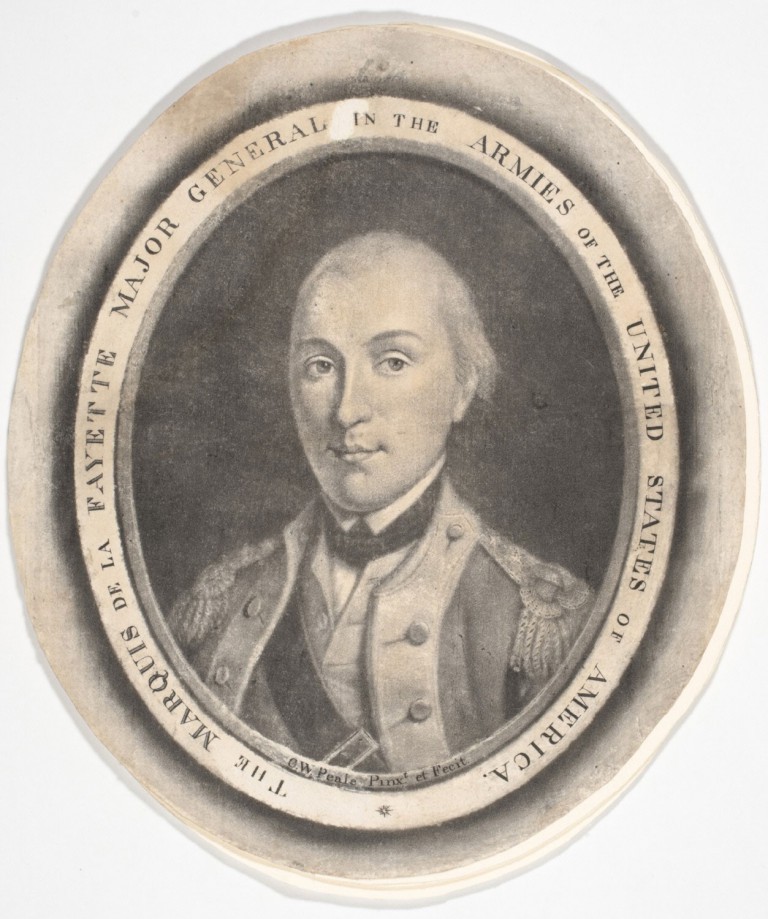

When the Marquis de Lafayette (1757-1834), a French hero of the American Revolution, returned to the United States in 1824-25, Philadelphians joined in a wave of nationwide affection for the nobleman who had volunteered for service in the Continental Army at the age of 19. Lafayette’s return to the region stirred increasing regard for preserving relics of the Revolution, especially the old Pennsylvania State House, which began to acquire a new name: Independence Hall.

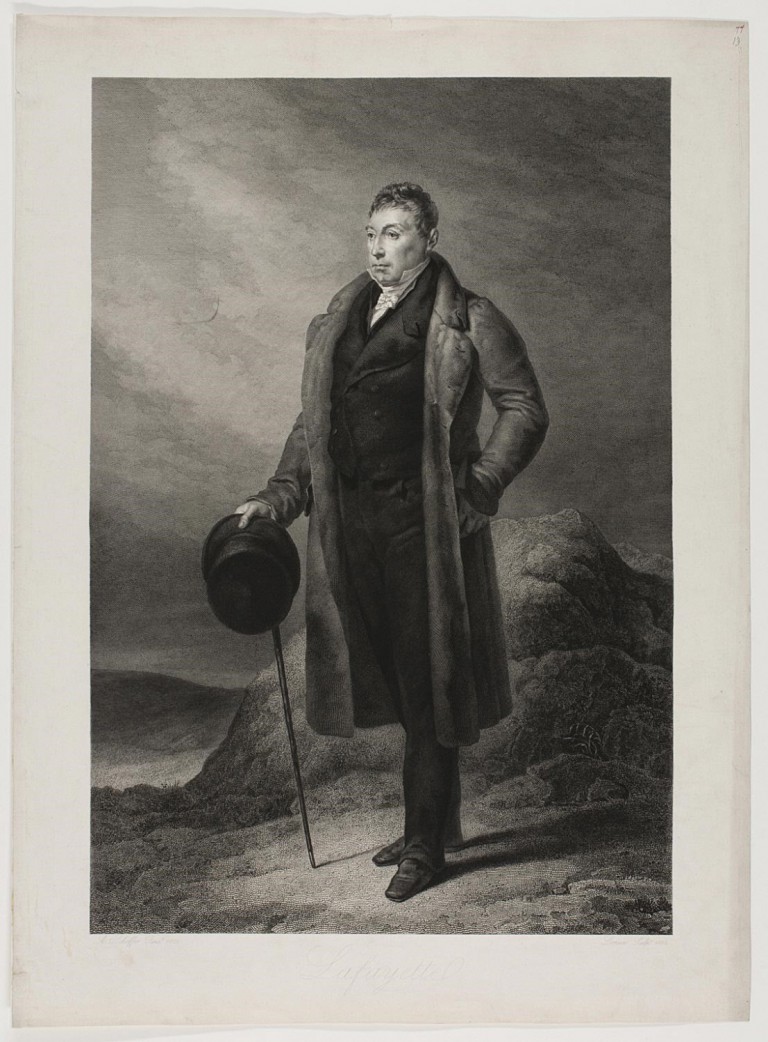

Lafayette (Marie Joseph Paul Yyves Roch Gilbert de Motier, Marquis de Lafayette) returned to the United States as the “nation’s guest” by invitation of his longtime friend President James Monroe (1758-1831). With the Declaration of Independence nearly fifty years in the past, Lafayette represented a generation of heroes soon to pass from living history into memory. Throughout the United States, his presence touched off elaborate preparations, pageantry, and a lively market for Lafayette keepsakes. The tour, originally intended to last four months, triggered such intense public enthusiasm that Lafayette stayed for thirteen months and traveled to all twenty-four states in the nation. He visited Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) at Monticello and the Mount Vernon tomb of his general and friend George Washington (1732-99).

Lafayette came to the Philadelphia region twice, near the beginning and end of his tour. In September 1824, after arriving in New York from France, he journeyed through northern New Jersey to Trenton, where he crossed the covered bridge over the Delaware River to Morrisville, Pennsylvania. Entertained at an evening ball at Holmesburg and then lodged overnight at the Frankford Arsenal, the next day Lafayette entered Philadelphia in a carriage pulled by six cream-colored horses and accompanied by a three-mile-long procession of citizens on horseback, public officials from Pennsylvania and New Jersey, military units, veterans of the Revolution, tradesmen, and farmers from the countryside. The parade followed a route carefully planned to pass impressive neighborhoods and landmarks and cheering throngs of onlookers on the way to the old State House. Temporary triumphal arches along the route ushered the marchers and riders through Northern Liberties into the city.

For nearly two months, Philadelphians had planned for the moment of Lafayette’s arrival. For his reception, an arrangements committee commissioned architect William Strickland (1788-1854) to refurbish the room in the old State House where independence had been declared. By that time in a state of neglect, the east room on the building’s first floor attracted renewed attention as it became transformed for the occasion. As Philadelphians acquired new mahogany chairs and sofas, draperies, and carpets to create a suitably lavish reception, they also coined a name for the room: the “Hall of Independence” or “Independence Hall.” Originally applied only to the first-floor room where independence had been declared, over subsequent decades the name became applied to the building as a whole.

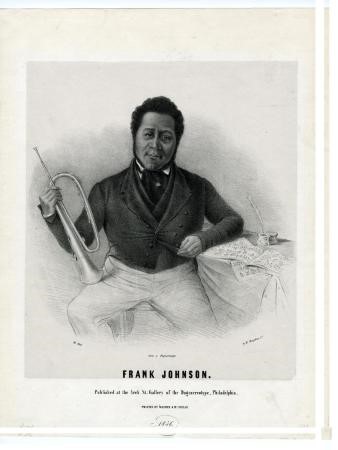

Lafayette’s reception in the Hall of Independence, during which he and Philadelphia’s mayor exchanged greetings and reflected on the historic events that transpired where they stood, established a precedent for other nineteenth-century guests, from dignitaries to visiting fire companies. Lafayette’s eight-day visit also created new attachments to the memory of the American Revolution for thousands of schoolchildren who assembled in the State House Yard to be in his presence, for residents who attended a celebratory civic ball at the Chestnut Street Theatre, and for those who adorned themselves and their homes with mass-produced souvenirs. “Everything is Lafayette, whether it be on our heads or under our feet,” the Saturday Evening Post commented in the aftermath. “We wrap our bodies in Lafayette coats during the day, and repose between Lafayette blankets at night.”

Departing Philadelphia, Lafayette traveled by steamboat on the Delaware River to Chester, Pennsylvania, which celebrated him with a parade and banquet, and from there to Wilmington, Delaware. When he returned to the region for a somewhat longer, but quieter, stay near the end of his tour in July 1825, his itinerary included visits to Germantown, Mount Airy, and Chestnut Hill. On the way south for departure from Washington, he stopped in West Chester (where an estimated ten thousand people gathered to witness his procession) and joined military units and aged veterans in a tour of the area of the Battle of Brandywine, where he had been wounded during the Philadelphia campaign.

Lafayette’s tour left lasting effects around the United States in the form of towns, counties, colleges, and streets bearing his name, projects to create monuments, and new regard for material relics of the American Revolution. In Philadelphia, historically-minded citizens formed the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in 1824. Some who served on the arrangements committee for Lafayette’s visit mobilized again 1828 to replace the steeple on Independence Hall, which had lacked this distinctive feature since the original rotted away more than four decades before. The new steeple served contemporary needs for a clock and bell, but the Philadelphia City Councils insisted that it must resemble as closely as possible the building as it stood at the time of the American Revolution.

Charlene Mires is Professor of History at Rutgers-Camden and Editor-in-Chief of The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Lafayette: Citizen of Two Worlds (Cornell University)

- Lafayette in America, 1824-1825 (Friends of Lafayette via YouTube)

- Lafayette Returns to Philadelphia (Independence Hall in American Memory Companion Site)

- August Levasseur, Lafayette in America in 1824 and 1825 (Google e-book)

- Biography of Marquis de Lafayette (National Park Service)