Public Markets

Essay

Public markets in Philadelphia belong to an ancient tradition of urban food provisioning in which the governing authority designated specific places for the exchange of life’s necessities. A formal and organized system of exchange was intended to attract local and regional producers to the city in order to ensure citizens an adequate supply of healthful food at fair prices. Public markets were critical to the survival of the town, because without them unbridled competition and unfair dealings in the sale of perishable food could jeopardize the public welfare.

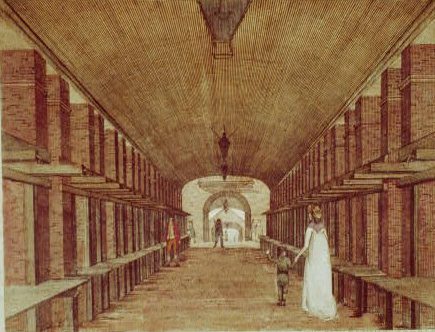

Market spaces served as hubs for convenience, commerce, and community. Following standard principles of town planning, William Penn (1644-1718) anticipated the need for extra-wide streets to accommodate farmers bringing produce into the city. High Street (later renamed Market Street), the principal east-west arterial extending from the Delaware River to the Schuylkill, was used for marketing from the time of the city’s founding. The market began at the waterfront, where an ornate headhouse and shed were reserved exclusively for New Jersey farmers, and additional sheds extended westerly with the growth of the city. By 1859 a continuous series of sheds extended from the Delaware River to Eighth Street and again from Fifteenth to Seventeenth Streets, with breaks only at the intersections.

The High Street Market was grouped by the type of produce for sale, such as meat, fish, dairy products, fruit, and vegetables. Household goods were also for sale and included pottery, ironware, baskets, shoes, and firewood. The market clerk—a mayoral appointee—assigned the stalls, collected rent and fines, inspected food for quality and proper weight and measure, and policed and swept the market. High Street Market’s impressive length, coupled with its notable quantity and variety of agricultural produce and manufactured goods, made it a model and the envy of rival cities such as New York and Baltimore. Local residents as well as travelers to Philadelphia consistently described it as one of the finest public markets in the country—famous not only for its graceful arcades, order and cleanliness, and merchandise, but also for its social and economic diversity. Shoppers attracted to its wide range of offerings came from all walks of life; and vendors ranged from the ubiquitous female hawkers of coffee, doughnuts, and pepperpot soup to the established dealers who sold fine meats, game, and fancy produce from permanent stalls year round.

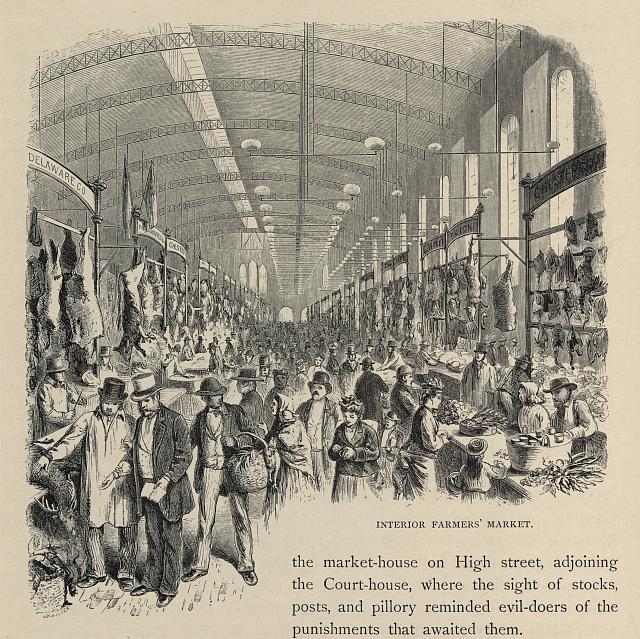

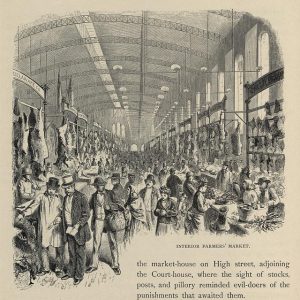

After the consolidation of Philadelphia city and county in 1854, Philadelphia began planning the removal of the market sheds from High Street in order to develop it as a modern commercial corridor lined with new buildings and unencumbered by market wagons, live animals, refuse, and other nuisances associated with outdoor marketing. High Street was renamed Market Street by a municipal ordinance of 1858, and the city demolished the sheds in 1859. In the wake of the demolition, seventeen market companies were incorporated in Philadelphia—chartered by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania to build fully enclosed, off-street market houses for the displaced vendors. Examples included Eastern Market (southwest corner of Fifth and Merchant Streets), Farmers’ Market (northeast corner of Market and Twelfth Streets), and Western Market (northeast corner of Sixteenth and Market Streets).

Market companies, with their legal authority to issue stock, raised capital for property and buildings, including the latest innovations in refrigeration, lighting, ventilation, and construction. Private market houses were characterized by their off-street locations, elaborate brick facades with architectural embellishments, and cavernous interiors with high ceilings that provided diffused light and ventilation. Interior stalls numbering in the hundreds were laid out in a grid and divided by broad aisles and narrow cross aisles. Patrons could make purchases from several different vendors in a comfortable atmosphere that was removed from the hazards of vehicular traffic and inclement weather. As such, the private markets were promoted for their high standards of service, modern facilities, and atmosphere of civility. The market house company movement that began in Philadelphia in 1859 spread throughout the commonwealth, particularly during the 1870s and 1880s, when other cities and towns, including Reading, Harrisburg, and York, tore down their municipal market sheds and encouraged private companies to assume the task of urban provisioning.

More than twenty-five new market houses were built in Philadelphia in the last quarter of the nineteenth century to meet the demand in rapidly growing neighborhoods, including the Norris, at Third and Norris Streets; the Centennial, at Twenty-Second and South Streets; and the Federal, at Seventeenth and Federal Streets. Among the more commanding and enduring market houses from this period was the Ridge Avenue Farmers’ Market, built in 1875 on the southwest corner of Ridge Avenue and Ginnodo Street in North Philadelphia. Davis E. Supplee (1864-1935), a Philadelphia architect, designed the market house in the High Victorian Gothic style, whose steeply pitched slate roof, long shed dormers, and tripartite window in the façade gave it a commanding presence. Complementing the Ridge Avenue Farmers’ Market were the open-air street markets still owned and operated by the city, on Bainbridge, Spring Garden, Callowhill, Girard, Wharton, and North Second Streets.

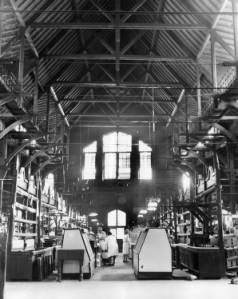

Reading Terminal Market officially opened in 1893 and ushered in a new era for urban food marketing and distribution in Philadelphia and the region. The Reading Railroad established the market after reaching a settlement with dealers from the vendor-owned Twelfth Street Market Company, whose market house was scheduled for demolition as the new railroad terminal was under construction. The Reading designed a market with eight hundred stalls underneath the elevated tracks of its mammoth terminal, and the market quickly developed a reputation for being one of the finest in the country. Reading Terminal Market was known for its innovative basement cold storage, where a ceiling-mounted roller system allowed goods to be moved easily on hangers through the corridors and into the cold rooms. A pump system sent chilled brine to refrigerated counters in the stalls above, and an on-site ice-making plant facilitated the provision of ice to dealers who required it for the preservation of perishables. Besides these innovations, business at Reading Terminal Market also benefited from a steady stream of commuter passengers.

(Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries)

Reading Terminal Market faced uncertain times during the 1970s and 1980s, when the Reading Railroad emerged from bankruptcy and sold its terminal buildings and grounds to the Pennsylvania Convention Center Authority (PCCA). Following a major campaign of the Merchants Association to save the market, the PCCA purchased Reading Terminal Market in 1990 and incorporated it into the new convention center. The market celebrated its centennial in 1992 and has maintained its reputation as one of the great public markets in the United States—serving a local customer base, while catering to thousands of conventioneers and tourists who frequent the market at lunchtime. Although it has responded to an increased demand for ready-made foods, it has preserved its historic character and maintained its policy of operating primarily as a provisions market—catering to buyers of premium-quality fresh produce and providing an important market for the Amish and Mennonite farmers in the region. Its customers benefit from the rich experience and longevity of the vendors, many of whom maintain decades-old relationships with their patrons and suppliers.

Coinciding with developments in retail markets were developments in the wholesale trade in Philadelphia, especially after the Civil War when growers in the southern states found it lucrative to ship produce to points north in order to meet a growing demand for year-round fresh produce. Refrigerated rail service facilitated the receipt of domestic and imported produce to Philadelphia’s freight terminals and rail yards, where bulk merchandise was redistributed to local, regional, and international markets. This expansion of the trade required intermediaries to handle the receipt, storage, packaging, and distribution of perishable food on a large scale, and wholesale markets handling massive tonnage developed in several key locations along the Delaware River waterfront, such as the Callowhill Street Market and the Dock Street Market. Dock Street was connected by rail spur to the produce terminals of the Baltimore and Ohio and the Pennsylvania railroads located farther south along the river.

During the Progressive Era Philadelphia joined other cities in considering construction of a new kind of market—the wholesale terminal market, where produce would be handled at a single location for reasons both practical and economic. The idea of a municipal terminal market for Philadelphia was suspended during World War I and not revived until the New Deal, when the Bureau of Agricultural Economics (BAE) of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) identified Philadelphia as one of forty cities that would benefit from a unified wholesale market designed along modern principles of food handling and open to all rail carriers, grower associations, independent farmers, chain store warehouses, packers, truckers, and wholesale food suppliers. A unified wholesale market would be the hub of a food distribution that not only served the city but also the region. According to a USDA study in 1936, the area of distribution from the Philadelphia markets included South Jersey (Atlantic City, Trenton, Camden, Asbury Park, and Cape May); a part of Delaware, including Wilmington; and the eastern part of Pennsylvania, west to Harrisburg and northward to Williamsport, Wilkes-Barre, and Scranton.

A consolidated wholesale market became a reality in 1949 during the term of Edmund Bacon (1910-2005) as executive director of the Philadelphia City Planning Commission—a post he held until 1970. Among other projects, the influential urban planner secured the removal of Dock Street Market from its historic location in order to clear the site for the redevelopment of Society Hill. This decision prompted construction of a replacement market in 1958—the Philadelphia Regional Produce Terminal located on South Galloway Street and Pattison Avenue. The complex accommodated not only the displaced Dock Street produce merchants but also Philadelphia’s meat and dairy product wholesalers, fruit auction houses, food packers and processors, packagers, and allied industries. The Philadelphia Regional Produce Terminal supplied the city’s retail food markets, which in 1958 included not only public and private market houses but also grocery stores, delicatessens, supermarket chains, specialty food shops, and retail cooperatives.

While the dealers in fish and other produce remained at the terminal on Pattison Avenue, the wholesale fruit and vegetable dealers relocated to the Philadelphia Wholesale Produce Market (PWPM)— a new facility that opened on June 5, 2011, at 6700 Essington Avenue. The Wholesale Produce Market became the world’s largest fully enclosed, fully refrigerated wholesale produce terminal, with the main building extending one-quarter of a mile and encompassing 686,000 square feet. Open to the public, the market established a nominal fee for anyone to enter and purchase produce by the carton from the twenty-four independent produce distributors operating as a cooperative. In 2016, the Wholesale Produce Market was receiving and selling hundreds of truckloads of fresh produce on a weekly basis. Customers ranged from Florida to Canada, though most came from within a 150-mile radius of Philadelphia.

Philadelphia’s well-developed market system continued in the early twenty-first century, despite the loss of some of its historic market houses. After decades of physical neglect, the Ridge Avenue Farmers’ Market–designated on the National Register of Historic Places in 1984— was demolished in March 1997 after its roof collapsed in a storm. Other neighborhood market houses, such as New Market on South Second Street between Pine and South, were revived by seasonal farmers’ markets—a nationwide movement that grew significantly in the late twentieth century as part of a negative public reaction to a globalized food industry. Contributing to the revival and survival of farmers’ markets in Philadelphia, USDA programs such as Women, Infants and Children (WIC), Farmers Market Nutrition Program (FMNP), and Senior Farmers Market Nutrition Program (SFMNP) provided recipients and eligible seniors with the resources to purchase fresh, unprepared, locally grown fruits and vegetables. Reading Terminal Market became the largest single site of SNAP (food stamps) redemption in Pennsylvania. Nonprofit organizations such as The Food Trust also managed farmers’ markets in communities lacking access to affordable produce.

Complementing a network of farmers’ markets, neighborhood markets such as the Italian Market, also known as the South Ninth Street Curb Market, in South Philadelphia continued to offer produce and ready-made foods associated with particular ethnic groups. The Italian Market’s many grocery stores, cafes, restaurants, bakeries, cheese shops, and butcher shops sustained a tradition of providing fresh produce and specialty foods in contiguous shops with colorful awnings over the sidewalks. Little Saigon, a large Vietnamese neighborhood located in South Philadelphia, converted low-rise strip malls into Asian grocery stores, restaurants, and other business during the wave of Vietnamese immigration in the 1990s. These markets, while not formally operating as such, supported independent food businesses concentrated at a single place for the benefit of the neighborhood or community while also creating a public space and a destination point for visitors.

Philadelphia’s public markets were once characterized by a formal network of neighborhood market buildings and open spaces restricted to bona fide farmers who sold produce direct to the household buyer. They evolved to include large wholesale market terminals whose dealers handled fresh produce, processed foods, and domestic and imported goods for sale to local, regional, and international buyers. Regardless of their type and scale of trade, they shared common traits with public markets worldwide—public goals and public spaces— that distinguished them from roadside stands, grocery stores, supermarkets, and other independent food retailing establishments.

Helen Tangires is the administrator of the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts at the National Gallery of Art. Her scholarly interests focus on the role of government in the regulation and construction of urban marketplaces for perishable food. She is author of Public Markets and Civic Culture in Nineteenth-Century America (Johns Hopkins University Press) and Public Markets (Norton/Library of Congress). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- Italian Market of Philadelphia

- Reading Terminal Market (Visit Philadelphia)

- Philadelphia Wholesale Produce Market

- Reading Terminal and Market Historical Marker (Explore PA History)

- Italian market, Philadelphia, PA, August, 2010 (Explore PA History)

- Headhouse Farmers Market

- A Bit Of History Lost As Ridge Ave. Farmers Market Collapses The Victorian Gothic Building In N. Phila. Will Be Razed. A Developer Says Officials Thwarted Plans For It. (Philly.com)