Korean War

By Levi Fox

Essay

Although active hostilities during the Korean War lasted for little more than three years (1950-53), the conflict had a lasting impact on the Philadelphia area. The war provided a boost for the shipbuilding industry on both sides of the Delaware River, and military bases played a major role in preparing soldiers and supplies for deployment. The sizable human toll in southeastern Pennsylvania, South Jersey, and Delaware, however, helped to encourage an anti-war movement in Philadelphia and attempts by students to circumvent the draft. In the aftermath, fatalities also motivated monuments to local citizens who served in the Korean War.

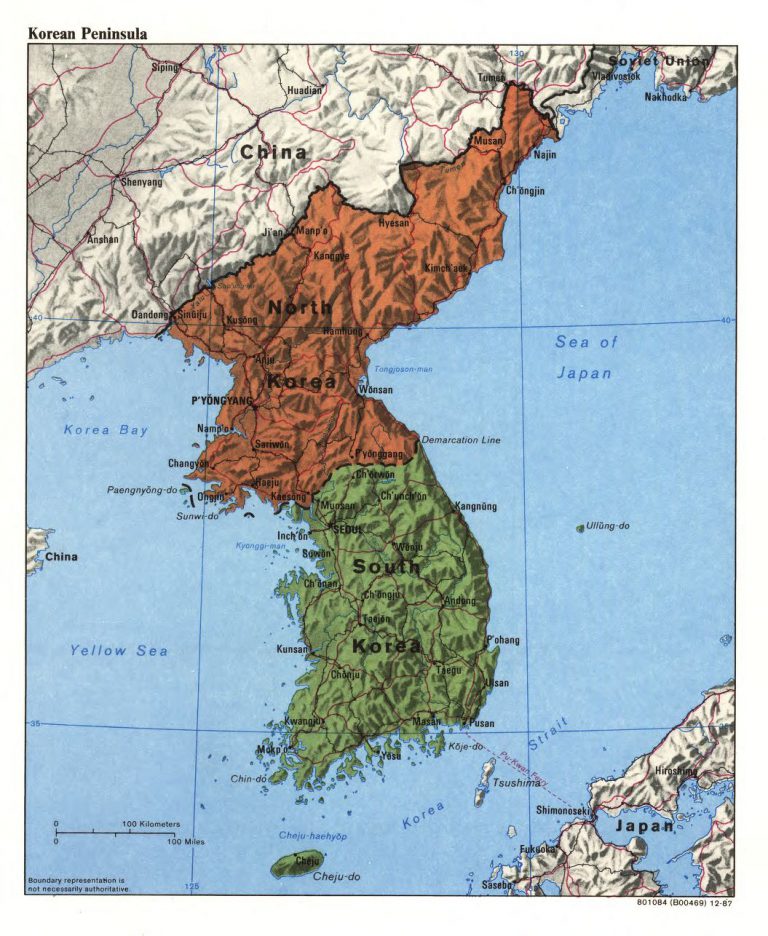

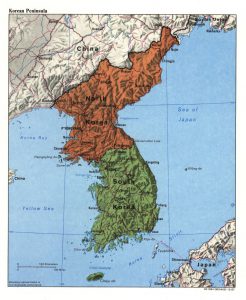

The Korean War resulted from conflict that followed the division of the Korean Peninsula after World War II into two political units, north (supported by communist Soviet Union and China) and south (backed by the United States). During the late 1940s, at the same time that similar ideological conflicts led to the “Iron Curtain” dividing Europe, these divisions as well as the Chinese Civil War fostered the advent of the Cold War in East Asia. The Korean War began on June 25, 1950, when the North Korean military invaded South Korea, and the internal conflict became international in the fall of 1950 after the United States persuaded the United Nations to send troops to stop the spread of communism by defending the South. While American public opinion supported the Korean War during the early months of the conflict, by January 1951 as the Chinese and North Koreans captured the southern capital, Seoul, for the second time, nearly half of those polled opposed American involvement, and support never fully rebounded.

For Philadelphia and the surrounding region, the onset of the Korean War brought about a spike in local employment. The Philadelphia Navy Yard experienced a temporary upsurge of 3,700 new jobs by the end of 1951, which led to a total workforce of more than 12,500 people. Primarily preparing United Nations ships for service in the Pacific Ocean, Navy Yard workers also modified seaplanes and submarines from World War II with modern technologies. The return of vessels from the front kept Navy Yard workers employed through the mid-1950s. The New York Shipbuilding Corporation in Camden experienced a similar surge in employment for constructing new ships and converting existing vessels.

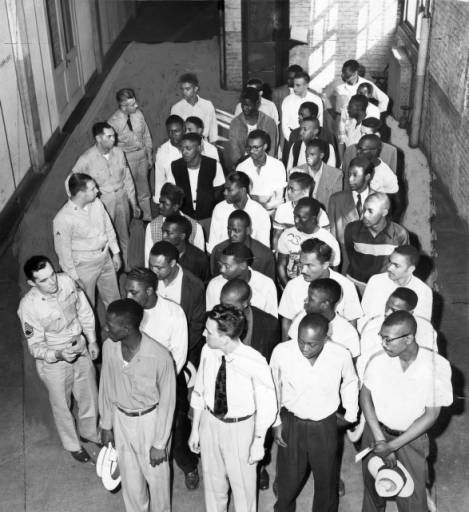

Military bases in New Jersey, Delaware, and eastern Pennsylvania also played a major role in the Korean War. Soldiers from across the northeastern United States reported to Fort Dix in New Jersey for basic training. During the first two years of the Korean War, jet fighter squadrons trained for combat at Delaware’s Dover Air Force Base, which also became the location for Air Mobility Command support services and strategic aerial defense of Washington, D.C. North of Philadelphia, the United States Naval Air Station at Willow Grove was home to the 111th Attack Wing of the Air National Guard, which trained on bombers such as the B-29 Superfortress before being assigned to the Strategic Air Command and deployed to Korea. The Philadelphia region also felt the human toll of the war. More than six hundred deaths in the war, over one-fourth the total for Pennsylvania, came from Bucks, Chester, Delaware, Montgomery, and Philadelphia Counties. In addition, forty-three Delawareans and nearly eight hundred New Jerseyans died in Korea.

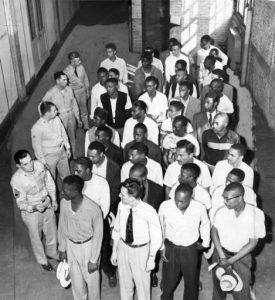

The region’s sizable local sacrifice, along with the presence of a socialist community that had supported Progressive Party candidate Henry Wallace (1888-1965) for president in 1948, helps to explain why Philadelphia became one of the centers of organized protest against the Korean War. The protest movement also drew strength from the longstanding local influence of Quakers and other pacifist denominations, such as the Mennonites, as well as from the large number of universities in the area. Throughout the Korean War the Philadelphia-based Central Committee for Conscientious Objectors (CCCO) counseled young people about their religious rights under the Selective Service System to avoid active combat, a protection not available for politically motivated pacifism. In order to be able to choose their branch of service, such as the Navy or Air Force rather than the Army, many Philadelphia-area college students volunteered to serve in the Korean War rather than wait to be drafted.

Doylestown native James Michener (1907-1997), who covered the war for The Saturday Evening Post, was one of the first people to use the term “Forgotten War” because he believed that by the latter half of the conflict the American public was wholly ignoring Korea. Although armistice negotiations to end the Korean conflict began in mid-1951, they took two years to conclude in part due to disagreements over the repatriation of prisoners of war who claimed that they did not wish to return to the Chinese or North Korean militaries. The war formally ceased on July 27, 1953, with the signing of an armistice ending active hostilities, but no permanent peace treaty was ever negotiated.

Local monuments dedicated to the deceased soldiers of the Korean War dot the landscape of southeastern Pennsylvania, southern New Jersey, and northern Delaware. The names of all Delawareans and New Jerseyans who died fighting in Korea are engraved on a wall in New Castle, Delaware, at the Delaware Memorial Bridge Park, dedicated in 1956. Monuments in Coatesville, Doylestown, and Philadelphia all remind residents and visitors of the sacrifices made during the Korean War. The Philadelphia Korean War Memorial at Penn’s Landing, dedicated in 2002, included four pillars containing the names of the war dead from the counties surrounding Philadelphia listed by year and two side walls with images including children, grandparents, nurses, and ministers as well as scenes of combat. Local memorials in southern New Jersey, the New Jersey State Korean War Veterans Memorial in Atlantic City, and museums at the Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst in New Jersey and Dover Air Force Base in Delaware similarly provided platforms for remembering the lasting impacts of the Korean War on Greater Philadelphia.

Levi Fox is a Ph.D. Candidate in Public History at Temple University and a former Allan F. Davis fellow at the Philadelphia History Museum at the Atwater Kent. Fox is also a blogger for the Mid-Atlantic Regional Center for the Humanities (MARCH) and teaches courses at Temple, Rutgers, and Stockton Universities. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University