Coffeehouses

Essay

Philadelphia’s first coffeehouse opened in 1703, and by mid-century half a dozen operated within the city limits. Their purpose, however, changed in important ways as the eighteenth century progressed. Early coffeehouses primarily served the needs of traders and mariners, acting as crucial centers of commerce. In the decades following the American Revolution, however, some coffeehouse functions—such as banking and maritime insurance—had developed into separate industries. As a result, proprietors reached out to new clientele, competing with taverns, inns, and hotels by offering elaborate menus as well as social and intellectual entertainments. Philadelphia’s coffeehouse scene transformed yet again in the twentieth century with the arrival of regional and national franchises. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, coffeehouses remained an integral part of the social fabric, with hundreds operating in the city’s center and scores more in surrounding neighborhoods and suburbs.

Early American coffeehouses were often modest ventures. A land deed for Philadelphia’s first coffeehouse, opened by Samuel Carpenter (1649–1714) in 1703 on Front Street just north of Walnut Street, described a “tenement” measuring just twenty-four feet wide by thirty feet deep. Later coffeehouses grew in size and often set aside rooms for special groups or functions. The coffeehouse opened in 1720 by a Captain Roberts, also on Front Street, had enough space to host board meetings of the Library Company, North America’s first circulating library. His wife, the “Widow Roberts,” continued to manage the business after his death until 1754. She was one of three women known to operate coffeehouses in Philadelphia by the 1750s.

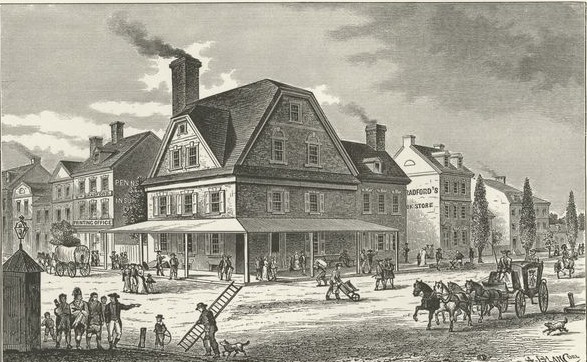

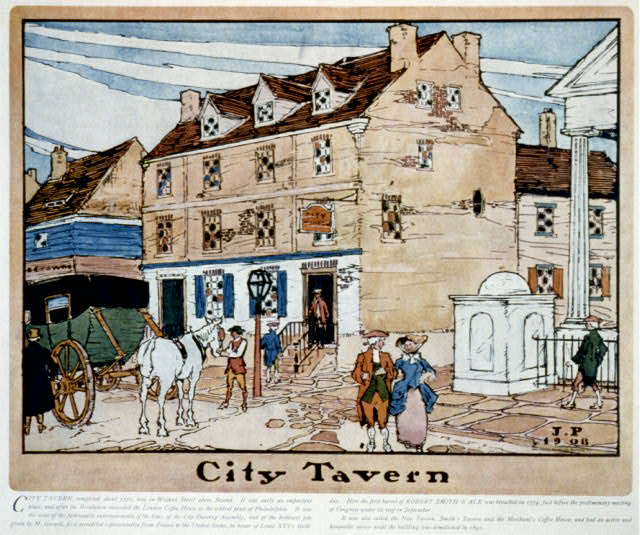

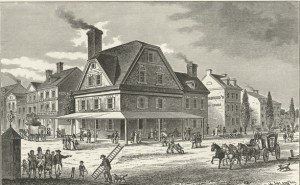

In some ways colonial coffeehouses functioned like taverns or inns. They offered food and drink, and both served coffee and alcohol. But there were also important differences. Coffeehouses were centers of commercial activity, particularly during exchange hours, when traders compared currency prices and bought or sold bills and coins. Period prints and paintings usually depict these first-floor spaces as large public halls, with communal tables dominating their centers and booths arrayed along the walls where more private business could be conducted. Even the front porches and walls of coffeehouses were put to commercial use. The space in front of the Old London Coffee House at Front and Market Streets was one of Philadelphia’s most popular auction blocks and was used to sell everything from imported bags of coffee and barrels of rum to indentured servants and enslaved Africans. The city sheriff even used the Old London four times a year to auction goods and property confiscated for nonpayment of debts.

Newspaper Subscriptions

Because of their business orientation, eighteenth-century coffeehouses subscribed to a variety of newspapers. In 1796, the Merchant’s Coffee House and Exchange boasted both local Philadelphia newspapers as well as periodicals from New York, Boston, Baltimore, and Europe, a subscription series costing a hefty £500 or more annually. Such publications were invaluable to savvy traders who needed to be kept abreast of the latest news, such as where hurricanes or foreign privateers were wreaking havoc, which goods were selling most quickly, and what styles and fashions had come into demand.

By the 1760s, the Old London was Philadelphia’s leading coffeehouse, owned by printer William Bradford (1719–91). Centrally located in the business district and adjacent to the waterfront, it was a well-known landmark. It was thus the ideal meeting place for merchants and storekeepers when they began formulating their responses to new, and largely unwanted, British commercial legislation and voicing their discontent. When several Philadelphia merchants and store owners assembled at the Old London to discuss their response to the Stamp Act in September 1765, political discourse quickly escalated into threats against John Hughes (1711–72), Philadelphia’s tax collector, that left him so terrified he would later recall how he had fortified himself “with Fire-Arms” and resolved “to stand a Siege” while several of his friends patrolled the neighborhood “between my house and the Coffee House.”

Hughes’s fears were well founded. During the American Revolution, local leaders used Philadelphia’s coffeehouses to stage ritual destruction of hated pieces of legislation, as well as to post the nonimportation agreements that they circulated and signed. Coffeehouses also hosted meetings of the city’s Committee of Correspondence, which sought to strengthen communication about protest between colonies, and the Committee of Compliance, which enforced the embargoes designed to compel Parliament to reconsider its approach to governing trade. The “deliberations of Congress are impenetrable secrets,” John Adams (1735–1826) mused from Philadelphia in 1775, “but the conversations of the city, and the chat of the coffee house, are free, and open.”

Coffeehouses Reinvent Themselves

By the 1790s and early 1800s, many of the commercial functions formally associated with coffeehouses had become professional industries in their own right, such as banks, insurance companies, post offices, and auction houses. As a result, coffeehouses had to remake themselves. Some relocated to the outskirts of town, such as Manayunk and Passyunk, or near suburban parks. Abraham Streaper (1747–92), for example, opened his coffeehouse on the banks of “that beautiful and airy situation on the west of the Schuylkill River” two miles from the city where he advertised a relaxing atmosphere, fresh fish in season, and the best liquors. With such amenities as gardens, summer houses, and country air for the genteel, they bore little resemblance to the mercantile coffeehouses of a generation before. Other coffeehouses expanded their services in the city. Some offered menus that changed by time of day and season of the year, competing with taverns and restaurants. Some entrepreneurs featured special shows, including lecturers on topics from philosophy to politics, scientific experiments, and traveling music or theater productions. Concert tickets for a chamber music performance were sold by the Merchants Coffee House and Exchange in 1783, and the following year Bradford’s coffeehouse featured the work of an itinerant scientist presenting “A Lecture on Heads.” The American Coffee House, which operated between 1831 and 1834 on the second block of Chestnut Street, was really more of a creative restaurant, replete with pools filled with turtles, fish and crabs cooked to order, and roaming black bear cubs, until the animals outgrew the venue.

These trends continued during the nineteenth century, as coffeehouses became less associated with the world of business and more with entertainment, culture, and the culinary arts. By the turn of the century, patrons of the region’s coffeehouses saw them as places to chat about the shows they had just attended, or as purveyors of artisanal breads and pies. In these respects, the coffeehouses of the late nineteenth century were much more like what would emerge in the years to come than the busy, noisy haunts of the eighteenth-century merchant.

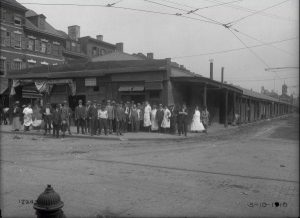

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the number of coffeehouses had declined in most urban settings. Too many kinds of businesses competed for the same diners, and the functions that had differentiated coffeehouses in earlier years had waned. In the 1920s, however, coffee shops slowly made a comeback. Like the first American coffeehouses, modeled after English antecedents, this latest iteration was a European import, although this time the inspiration came from Italy. A small coffeehouse in New York’s Greenwich Village, which installed an Italian espresso machine in 1927, claims to be the first Cappuccino bar, but Philadelphia was not far behind. Several coffee shops clustered around Ninth and Christian Streets, in what became known as the Italian Market.

Most of these venues initially served a very local clientele, recreating experiences that migrants had left behind. But the association of coffeehouses with alternative authors and songwriters, particularly the Beat Generation of the 1950s, revitalized the institution. The Gilded Cage, a coffeehouse opened by Esther (c. 1930–2009) and Edward Halpern (c. 1928–2006) at Twenty-First Street and Rittenhouse Square in 1956, exemplified this era. It became a popular venue for folk musicians, including Peter, Paul & Mary, Pete Seeger, Arlo Guthrie, and Simon and Garfunkel, until closing its doors in 1969.

The 1990s witnessed a new iteration of the coffeehouse, as what became known as the Starbucks generation emerged. The first Starbucks opened in Seattle in 1971, and the company went public in 1992. By 1995, Starbucks had come to Philadelphia. By 2015, almost two dozen Starbucks coffee shops operate in the city, alongside other franchises such as Dunkin’ Donuts, regional chains such as Philadelphia-based La Colombe, and scores of independent operators. The end result was a profusion of choices for the modern coffee drinker, catering to a wide range of different tastes and price points, but all reinforcing the centrality of coffee in modern American life.

Michelle Craig McDonald is an Associate Professor of History at Stockton University, where she teaches courses on early American and Atlantic world history, as well as museum studies. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Quest for the best cup of joe in Philadelphia (WHYY, November 25, 2010)

- East Falls cafe blends art with coffee and community (WHYY, October 10, 2011)

- Camden coffee shop prepares taxes along with breakfast — and that's just the start (WHYY, April 16, 2012)

- Germantown church's coffeehouse event promotes unity through the arts (WHYY, February 13, 2013)

- Philly coffee shop named top in the nation (WHYY, April 4, 2013)

- Philly cafe offers a cup of coffee, some cake, and frank conversations about death (WHYY, September 30, 2013)

- Protesters demand firing of Philadelphia Starbucks manager following arrests of two black men (WHYY, April 15, 2018)

- NAACP says Starbucks incident part of a national trend of discrimination (WHYY, April 17, 2018)

Links

- London Coffee House (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- High Street Hope (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- The First and Only to One of Many: How a Coffee Shop Helped Transform Spruce Hill (The PhillyHistory Blog)

- PhilaPlace: The City Tavern Restaurant — A Taste of Philadelphia History (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)