Edge Cities

By Stephen Nepa

Essay

Edge cities, as they came to be called, emerged on the peripheries of older urban centers in the last part of the twentieth century. As defined by journalist Joel Garreau (b. 1948), they contained at least five million square feet of leasable office space, 600,000 (or more) square feet of leasable retail space, “more jobs than bedrooms,” and a wide offering of occupational and recreational opportunities. Whether a singular municipality or a group of intermingling towns (at times spanning more than one state), they appeared nationwide, including several within Greater Philadelphia. By the 2010s, however, many undeveloped areas between the region’s older and edge cities themselves also clustered residents, jobs, and places for leisure, thereby challenging Garreau’s widely cited definition.

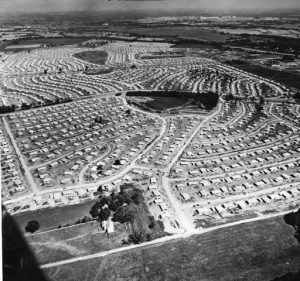

Garreau popularized the term “edge city” in his 1991 book Edge City: Life on the New Frontier. He argued that the phenomenon grew out of postwar suburbanization, the building of interstate highways, and “new towns” conceived by planners including Ray Watson (1926-2012) and Robert E. Simon (1914-2015). Their proliferation accelerated urban decentralization while at the same time reflecting the shift from manufacturing to service- and information-based economies. In some cases, they developed in rural areas or near existing transportation infrastructure (rail lines and secondary highways) while others resulted from new roadways, shopping malls, and the embrace of “car culture.”

Following World War II, population and job losses severely damaged Philadelphia and Chester, Pennsylvania; Camden and Trenton, New Jersey; and Wilmington, Delaware. At the same time, early postwar suburbs, such as Levittown and Springfield, Pennsylvania; Duncan Woods and Sherwood Park, Delaware; and Willingboro, New Jersey, accommodated a growing middle-class in communities that later included their own shopping centers, churches, and schools. Yet many residents still commuted to central cities for work and leisure activities. By the early 1960s, following the opening of new interstate highways, edge cities formed in rural portions of Burlington and Camden County, New Jersey; New Castle County, Delaware; and in Chester, Bucks, and Montgomery Counties to the north and west of Philadelphia. In the process, Greater Philadelphia’s older cities struggled to remain relevant.

Along with expressways, many edge cities owed their founding to the modern shopping mall. In 1961, the Cherry Hill Mall, then the nation’s largest enclosed shopping facility, opened in Delaware Township, Camden County. Designed by Victor Gruen (1903-80), it included dozens of stores, a food court, tropical atrium, art exhibits, a four-hundred-seat auditorium, and acres of free parking. Located four miles from the interchange of US Route 30, US Route 130, and New Jersey Route 38, the mall grew into one of South Jersey’s main commercial centers and over time drained economic activity from nearby Camden and Philadelphia’s aging department stores. The town of Cherry Hill, renamed from Delaware Township the same year, emerged as a prosperous edge city, luring pharmaceutical firms, auto dealerships, corporations such as Subaru of North America, and an NJ Transit rail stop. In 2003, demolition of its sixty-year-old horse track commenced to make way for Garden State Park, a mixed-use complex of condominiums, restaurants, and upscale stores totaling more than one million square feet. The building of the New Jersey Turnpike in the 1950s and the opening of the Moorestown Mall in 1963 boosted the Moorestown-Mt. Laurel area to the east in Burlington County. Bisected by I-295 and the New Jersey Turnpike, the affluent edge city attracted college campuses, waterparks, corporate tenants, and upscale restaurants.

Chester and Montgomery Counties

Upon completion of the Schuylkill Expressway (I-76), edge cities developed in Chester and Montgomery Counties. In 1963, the King of Prussia Mall opened near Valley Forge. Expanded over the years, the shopping complex located at the junction of I-76, the Pennsylvania Turnpike, and US Routes 202 and 422, ranked in 2017 as the nation’s second-largest mall. In addition King of Prussia hosted more than sixteen thousand jobs, in health care, utilities, and energy, among others. To suit convention traffic, the 240,000-square foot Greater Philadelphia Exposition Center opened in 2009. For entertainment and gaming, the Valley Forge Casino Resort opened in 2012 five miles away.

Conshohocken, a former factory city eight miles east, by the late 1990s had attracted chain hotels, apartments and restaurants, and the headquarters of design firms and security companies. Combined with nearby Norristown (the Montgomery County seat) the three cities formed a metropolitan area in its own right, with links to central Philadelphia by trains, bus lines, and several roads. In nearby Malvern, Pennsylvania, the Great Valley Corporate Center opened in 1974. Touted by then-president Ronald Reagan (1911-2004) in 1985 as the “workplace of the future,” the expanded complex employed more than twenty thousand and was home to biotech, financial, and medical firms. In 2015, plans unfolded to redesign the area into a walkable, mixed-use community with over one million square feet of stores, offices, and condominiums. Located just north of US Route 202 and US Route 30 and serviced by SEPTA regional rail, the Malvern area also included Paoli and Exton. Elsewhere in southeastern Pennsylvania, the Warminster-Willow Grove and the Bensalem-Levittown-Langhorne areas experienced edge city-style growth.

Adjacent to I-95 between Wilmington and Newark, Delaware, the Christiana Mall opened in 1978. Beginning in the 1980s, after much of Wilmington’s industry disappeared, the unincorporated Christiana-Churchman’s Crossing area attracted firms such as Astra-Zeneca, Christiana Hospital, shopping centers University Plaza and Centre Point Plaza, hotels catering to business travelers, and a SEPTA regional rail station. North of downtown Wilmington, the Concord Mall opened in 1965 along US Route 202; by 2016, the US 202-US 1 axis, extending north into Talleyville, Delaware, and Chadds Ford and Concordville, Pennsylvania, contained office parks, shopping centers, and thousands of single-family homes. Reflecting the area’s commercial importance, in 2014 Chester County officials proposed a feasibility study for resuming rail service to central Philadelphia, which had been eliminated in the mid-1980s.

In the nearly three decades following Edge City’s publication, Garreau’s definition faced criticism. Edge cities had grown significantly, ultimately blurring the lines between them and older cities. Philadelphia experienced an economic resurgence in the 1990s and early 2000s that attracted “millennials” and “empty nesters,” while older towns such as Haddonfield, New Jersey; Ardmore, Pennsylvania; and Newark, Delaware, saw revitalization of their downtown areas. In 2016 Camden, long beleaguered by job loss and high crime, heralded a $1 billion waterfront development proposal by Liberty Property Trust. Urban planner Robert Lang (b.1959), charting the amount of office space in the region, reasoned in 2006 that while King of Prussia and Paoli, Pennsylvania, still retained edge city characteristics, other towns, including Christiana, Warminster, and Cherry Hill also witnessed high rates of occupational dispersal and outward growth. Along the I-295 corridor in South Jersey, the US 202-US 1 corridor in Chester County, Pennsylvania, and US Route13 in New Castle County, Delaware, clusters of office parks, retail stores, and housing appeared to form large conurbations, or what Lang termed “edgeless cities.” They not only competed with Greater Philadelphia’s traditional urban centers for population and revenue but refuted Garreau’s contention that edge cities were bound to outpace other suburban concentrations, even to the point of rendering them obsolete.

Stephen Nepa teaches history at Temple University, Moore College of Art and Design, and the Pennsylvania State University-Abington. A contributor to numerous books, journals, and documentary films, he is currently working on a project about urban ruins. He received his M.A. from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and his Ph.D. from Temple University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Del. River waterfront efforts advance (WHYY, January 28, 2012)

- Can the Moorestown Mall make a comeback? (WHYY, September 23, 2013)

- Retail expansion projects on track at Delaware's Christina Mall (WHYY, April 4, 2013)

- Chester city government battles 'epidemic' violence (WHYY, July 11, 2014)

- Reinventing the American mall: Can the Burlington Center Mall be revived? (WHYY, September 15, 2014)

- Explainer: How transit villages help NJ combat sprawl, car culture (WHYY, September 3, 2015)

- Two skyscrapers on Camden waterfront? Philly developer eyes 2018 opening (WHYY, September 24, 2015)

- Allentown mixed-use waterfront development breaks ground (WHYY, October 22, 2015)

- How the King of Prussia mall keeps expanding (WHYY, August 18, 2016)