Nursing

Essay

The history of nursing in the Philadelphia area is one of long and storied traditions. Men and women have often nursed their sick families and friends at home, which for millennia represented the best, safest, and most comforting site for treatment and care. Bringing a stranger into that home to provide nursing care was a momentous decision. The idea of hired nurses—of paying for nursing—raised profound ambivalence: it could leave an individual at the mercy of one from a lower social class. Philadelphia’s nursing pioneers changed that idea as they and the institutions they served created new and respected opportunities for service to the sick.

Philadelphia’s earliest hired nurses tended to be older white women, pushed into the labor market by the poverty and destitution that accompanied widowhood or abandonment. But epidemics upended the traditional racial and gendered order. During the 1793 yellow fever epidemic, one of the deadliest in the country, white Philadelphians turned to the Free African Society for Black nurses because they believed in the commonplace idea of Black immunity to yellow fever. The society, founded in 1787 as a mutual aid society to care for poor Black widows, orphans, and the sick Black poor, oversaw the hiring of nurses from its community. At the same time, white men entered nursing. While most who had the means fled the city, Stephen Girard (1750-1831) and others stayed and nursed victims of the epidemic. Historians have argued that in the early Republic men, although not formally trained, provided nursing care when it required bravery and courage, but they relinquished the role when it involved the more tedious activities of nursing the sick.

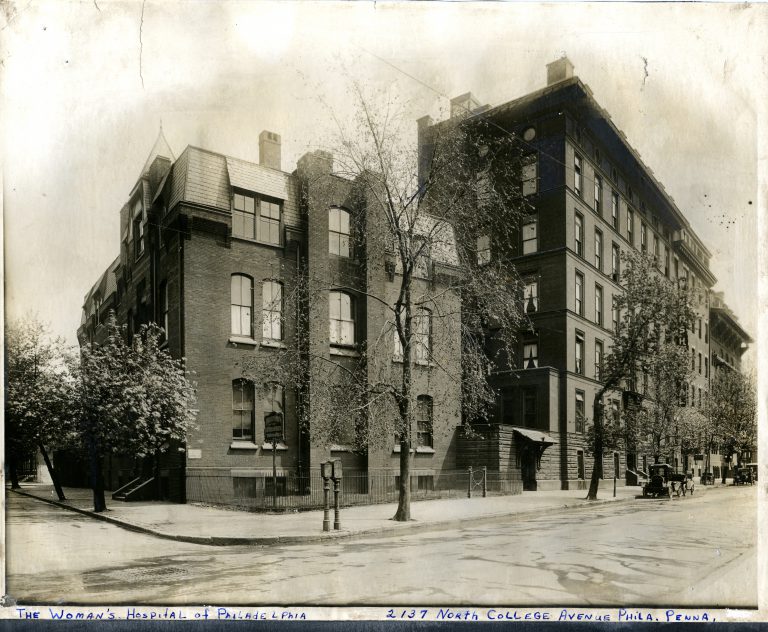

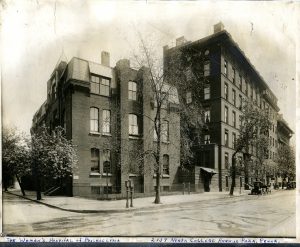

A small, more formally trained group of Philadelphia physicians long recognized the value of training women as their assistants. Efforts to provide formal training for women nurses began in the decades prior to the Civil War but attracted few students, perhaps because there was little about nursing that working-class women did not already know. In 1839 Joseph Warrington (1805-88), a respected Quaker physician, started the Nurse Society of Philadelphia to train white working-class women to assist him caring for mothers in childbirth in their own homes. Few women enrolled. In 1842, Joseph Longshore (1809-79), another Philadelphia physician, tried again. He published The Principles and Practice of Nursing, but sales were disappointing. In 1861 Ann Preston (1813-72), a student and later colleague of Warrington and Longshore, simultaneously opened the Woman’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the Woman’s Hospital Training School for Nurses. The formal training school failed as a recruitment strategy for women to nurse the hospital’s patients, but some historians argue for its place as the first formal training school for nurses in the United States. Its graduates provided examples of the skills of trained nursing to other area hospitals.

Even the well-known adventures of Florence Nightingale (1820-1910) in the Crimea and her widely popular Notes on Nursing: What it is and What it is Not, serialized in Philadelphia’s newspapers when the American version appeared in 1860, represented little new knowledge. Her brilliance lay in codifying widely diffuse principles of good sanitary practices so that they could be applied in homes, which were then the sites of the best health and illness care. Her book covered such topics as how to supply fresh air to sickrooms, how to provide a nutritious diet, how to ensure proper cleanliness, and how to maintain the quiet and order that was necessary for recuperation. Its audience was white middle-class mothers. Nightingale published a lesser known book, Notes on Nursing for the Laboring Classes, in 1861, aimed at the white working-class women who actually did the work of nursing.

The Civil War marked a watershed moment. Samuel Gross (1805-84), an eminent Civil War surgeon and professor at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia, noticed that patients in well-organized and well-nursed Northern war hospitals staved off the deadly infections that came with amputations and other kinds of complicated surgeries. By the 1870s a growing chorus of voices supported the idea that the advance of American medicine depended upon well-trained women learning to nurse in hospitals. And now these women agreed. They agreed to trade first two, later three, years of work nursing hospital patients in exchange for explicitly medical knowledge that would differentiate their care from those of mothers. Growth started slowly. By 1890 the United States had fewer than 500 trained nurses, but then the numbers exploded to 3,500 by 1900 and more than 8,000 by 1910.

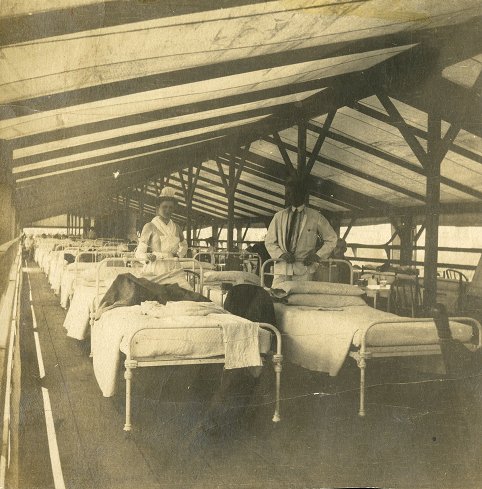

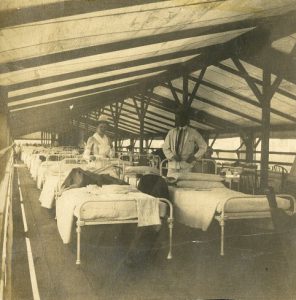

The origins of the Philadelphia General Hospital (PGH) Training School for Nurses reflected many of these themes. Initially, in 1876, the hospital contracted with the Woman’s Hospital Training School for students to nurse its women patients. But soon afterward, a major scandal involving inadequate nursing staff at this municipal hospital forced a reorganization and a recommitment to patient care. As the cornerstone of this project, the hospital opened a new training school for nurses led by a nurse who had been trained by Florence Nightingale. In 1885, Alice Fisher (1839-88) opened the training school with fifteen students. By 1916, twenty-eight trained nurses supervised the care of 145 patients across ninety-six wards with two thousand patients.

The Growth of Professional Nursing

By 1932, Philadelphia had 44 hospitals, almost all with their own training schools for nurses. Like the American healthcare system, training for nurses in Philadelphia was segregated—by race, ethnicity, religion, geography, and gender. Douglass Hospital, which opened its training school in 1895, and Mercy Hospital, which followed in 1907, trained Black women to nurse. The Hospital of the Protestant Episcopal Church, which started its training school in 1888, Methodist Episcopal (1892), Jewish (1892), and Presbyterian (1895) Hospitals trained women of their own faith traditions. St. Agnes, which began its school in 1894, trained Catholic women in South Philadelphia, and Miseracordia, which followed in 1918, trained those in the rapidly growing neighborhoods of West Philadelphia. St. Joseph Hospital, building on a long history of training those who would nurse in their religious lives, opened its formal nurse training school in 1894; it opened one for men who would nurse as brothers or monks in 1909. This pattern repeated throughout the region. It was not possible to provide nursing care to any hospitalized patient without a training school for nurses. Until the early 1920s, nursing students provided almost all of the care within the hospital’s walls. They left the hospital when they graduated, and a new round of students replaced them.

Psychiatric institutions across the country also formed training schools for men. In Philadelphia, the venerable Pennsylvania Hospital, which had opened its training school for women in 1883, added training for men in 1914 at its highly regarded department for mental and nervous diseases at its West Philadelphia campus. Much to the disappointment of these men, they were banned from serving as nurses during both World War I and World War II because of their gender seemed inappropriate for the task. Men could not serve as nurses in the military until 1955. Black nurses were excluded until 1941, and historians have argued that is was easier to imagine a woman, irrespective of race, providing the intimate tasks of nursing care than it was a man.

As numbers grew, so did work opportunities. Most nurses from training schools entered what became known as the private duty labor market: they went into a family’s home to nurse a sick individual. A very small number worked as educators or administrators in hospitals. But as the late nineteenth century gave way to the twentieth, a new generation of both physicians and nurses found opportunities in the new science of public health. Laboratories had identified the microbes that caused such deadly diseases as tuberculosis, diphtheria, and typhoid; scientists had discovered the means by which they spread through communities; and a new field of public health nursing emerged to bring information about disease prevention and health promotion to poor, immigrant individuals, families, and communities most at risk. A new field of public health nursing coalesced around the idea of nursing the sick poor and teaching them the behaviors that would keep them well.

Philadelphia’s Visiting Nurse Society, one of the earlier of such public health nursing organizations, began in 1886 when a small group of philanthropic women decided to hire a nurse to provide care to the sick poor in their homes. The service quickly grew not only in Philadelphia but in other large urban areas across the country. It capitalized on a steady stream of income from insurance companies, which quickly realized that a visiting nurse made it less likely that an insurance policy would have to pay death benefits. The Visiting Nurse Society also began sending nurses into schools to check for such infectious childhood diseases as ringworm, conjunctivitis, and rickets. Most importantly, its nurses went home to home teaching families individually or in community events about the prevention of diseases and about the importance of prenatal care. Mortality and morbidity rates from infectious diseases had already begun their descent, but the work of public health nurses accelerated the decline.

Almost simultaneously, and in keeping with the norms of segregation, the Philadelphia Starr Centre Association, a mutual aid and self-help society, began providing social service assistance to the Black families of South Philadelphia. By 1905, it added a health clinic at 729 Lombard Street staffed by a physician and, in 1906, by a nurse from the VNS. White philanthropists provided initial funding and the Centre was able to soon hire a Black nurse to work with the neighborhood families. By 1907, the Starr Centre nurse cared for over three hundred individuals and families.

As is true in all military conflicts, World War I severely taxed the ability of nurses to meet the demands of the military abroad and hospitals and public health agencies at home. But after the Armistice, another pressing problem arose. Private duty nurses would care for the wealthy, and public health nurses would care for the poor. But who would care for the vast middle class who also needed care when ill? The 1920s saw intriguing experiments with the organization of nursing services in the growing health care system. These included insurance that would pay for sick nursing in the home, plans to charge for nursing by the hour rather than by the day, and nurse-managed health clinics. But the Great Depression hit nurses hard. Declining family fortunes dramatically reduced the calls for private duty nursing, and declining tax and philanthropic revenues dramatically reduced the numbers of public health nurses. Unemployment among nurses remained so severe that the Works Progress Administration of President Franklin Roosevelt (1882-1945) created a special program for nurses. By 1936, six thousand nurses worked in seventeen projects across the United States in both urban and rural areas of the country.

The pendulum swung again as the United States prepared to enter World War II. Would there be enough nurses? There were not. In 1943, congressional action created the Cadet Nurse Corps. Any woman who wanted to attend an approved nurses’ training school would have her tuition, room, and board covered by the federal government if she promised to serve “for the duration.” Nurses training schools expanded rapidly as the Cadet Nurse Corps also included monies for facilities, instructional costs, and faculty salaries. Almost every training school in the Philadelphia area, including those for Black students, received Cadet Nurse Corps monies and expanded their training schools. When the war ended in 1945 and the military no longer needed the cadet nurses, a new question arose: What would happen when a flood of new graduates hit the health care labor market?

Both returning military and cadet nurses faced a changing health care landscape in the immediate aftermath of World War II. Partly because of the new availability of penicillin, partly because of more aggressive surgical interventions, and partly because of an increasing sense among patients and their families that even the gravest patients needed more aggressive care, the hospital became the epicenter of the country’s health care system. The 1946 Hospital Survey and Construction Act, more commonly known as Hill-Burton, committed federal dollars to help states achieve a ratio of 4.5 beds per 1,000 Americans. Hill-Burton helped established hospitals in the Philadelphia region expand their numbers of beds and it helped suburban communities establish what became known as the “community hospital system.” The organization of hospitals themselves were changing. New spaces—such as recovery rooms, coronary care units, and critical care units—needed new nurses with new kinds of more specialized knowledge. And nursing was changing. In 1946, the boards of both the American Nurses Association and the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses endorsed the principle of one integrated professional association. It was the first healthcare profession to do so. Philadelphia’s Fellowship Commission, one of the country’s oldest human rights organizations, was instrumental in this process.

New spaces for a changing discipline created the need for new knowledge. The collegiate education in nursing had started in a few places earlier in the twentieth century. But these programs grew rapidly after World War II. Some universities, like Yale, had freestanding schools of nursing. Most others, like that at the University of Pennsylvania, had begun as bachelor’s degrees in nursing education in schools of education. Penn began that program in 1935. By 1950, Penn had a free standing School of Nursing that awarded a baccalaureate degree to those with two years of liberal arts education followed by three years of clinical training, a first for the state. But the shortages of nurses during World War II spurred experiments in shortening the length of time it took to become a fully trained nurse. Community colleges in the Philadelphia region and across the country embraced the idea of granting the associate degree in nursing following two years of focused training. Under state-mandated registration laws, three pathways could lead to the title of “registered nurse”: the traditional training school, collegiate programs, and associate degree programs.

The many federal programs inspired by the Great Society agenda of President Lyndon B. Johnson (1908-73) looked to solve these problems. In 1964 alone, the Nurse Training Act sent nurses to school and the Nurse Scientist Graduate Training Program sent nursing faculty to doctoral programs to prepare to teach and research nursing questions in the collegiate programs that were increasingly important in nursing’s educational landscape. With more broad-based, employer-sponsored private insurance programs and the introduction of Medicare and Medicaid, increased demand produced acute shortages of primary care and pediatric physicians. This shortage prompted grassroots collaborations between like-minded physicians and nurses that resulted in nurses with more knowledge, autonomy, and skills in these practice areas. As time passed these collaborations became codified in, first, certificate programs, and then graduate programs in nursing producing skilled nurse practitioners that quickly expanded beyond primary care and pediatrics into acute care hospitals and health systems.

Philadelphia also gained a center for scholarship on the history of nursing after Joan Lynaugh (b. 1935), one of the co-founders of the nurse practitioner movement with her physician colleague Barbara Bates (1928-2003) while at the University of Rochester, came to the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing in 1980. Although hired to run its new primary care nurse practitioner program, she also came to establish a Center for the Study of the History of Nursing. The center, opened in 1985 and later named the Barbara Bates Center for the Study of the History of Nursing, became the preeminent center for historical scholarship and archival holdings.

The Philadelphia region’s nurses and nursing programs played a significant role in producing the health care system of the early twenty-first century. In 1960, the United States had 279 registered nurses per 100,000 people; that increased to 560 in 1980 and 1,000 in 2014. Nurse practitioners numbered 58 per 100,000 in population and work in a broad range of clinical specialties, including geriatrics, anesthesia, midwifery, and mental health. Nurses formed the backbone of the American health care system, and Philadelphia was the birthplace of much of that success.

Patricia D’Antonio is the Carol E. Ware Professor in Mental Health Nursing, Director of the Barbara Bates Center for the Study of the History of Nursing, and Chair of the Department of Family and Community Health at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing. She is also a senior fellow at the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics and core faculty in Gender, Sexuality and Gender Studies at the University. She is the author of American Nursing: A History of Knowledge, Power and the Meaning of Work (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010) and, most recently, Nursing with a Message: Public Health Demonstration Project in New York City (Rutgers University Press, 2017). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Nurses enivision a growing role in tackling healthcare challenges (WHYY, October 7, 2011)

- Focus on patients convinces doctors, nurses to wash hands (WHYY, September 5, 2011)

- Union criticizes holiday pink slips for Philadelphia school nurses (WHYY, December 9, 2011)

- South Jersey hospital-nurse standoff stuck in legal limbo (WHYY, March 28, 2013)

- School nurses are an essential part of a student's life (WHYY, June 7, 2013)

- Pa. bill would allow nurse practitioners to work independent from doctors (WHYY, March 23, 2015)

- Nurses push dueling fixes for understaffed Pa. hospitals (WHYY, May 11, 2015)

- Pa. nurse practitioners and doctors wage turf war (WHYY, October 16, 2015)

- Nurses At The Top (WHYY, January 19, 2016)

Links

- Philadelphia General Hospital Photo Collection

- Nursing Through Time (Penn Nursing School)

- PhilaPlace: Philadelphia General Hospital (Old Blockley): Philadelphians "Ain't Goin' to no Bellevue" (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Black Nurses and the 1793 Philadelphia Yellow Fever Epidemic (WorkingNurse.Com)

- Philadelphia, Nurses, and the Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918 (Naval History and Heritage Command)

- Keeping the Children Well (PhillyHistory Blog)