Mummies

By S. J. Wolfe | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

Philadelphia’s fascination with Egyptian mummies began modestly, but by the end of the nineteenth century the city held some of the largest collections of mummies in the United States. Although some mummies had only a transient stay in Philadelphia or were lost to the ravages of time, many remained in museums to teach later generations about ancient cultures and religions.

The ancient Egyptians believed in sympathetic magic—the idea that a representation of an object could become the real object in the afterlife. Therefore, in order to experience the afterlife, the body, or a representation of the body, would have to survive so that the life essences would bring the body to life in the afterworld. Preparation for this consisted of removing soft internal organs and wrapping the dead person in layers of linen soaked in ointments and preservatives. Many mummies were buried in elaborate coffins bearing their names and titles as well as spells for resurrection in the afterlife. Accompanying the mummy would be objects of everyday life that would magically become real in the afterlife.

The fascination with these mummies began in England and France in the early eighteenth century, when travelers brought mummies back from Egypt. As curiosities, mummies were unwrapped as a matter of innate interest about the preserved bodies and searched for amulets or other jewelry placed between the bindings. About a half century later, mummy specimens began to arrive in Philadelphia and elsewhere in the American colonies. The artist Benjamin West (1738-1820) presented a delicate arm and hand to the Library Company of Philadelphia in 1767. Silversmith John Germon (1782-1825) was said to have imported some mummies in 1800, but they subsequently disappeared until 1832, when workmen discovered the dilapidated cache while digging in a cellar at Third and Arch Streets. Only one remained intact and was in the hands of a private family in Southwark until at least August 1848.

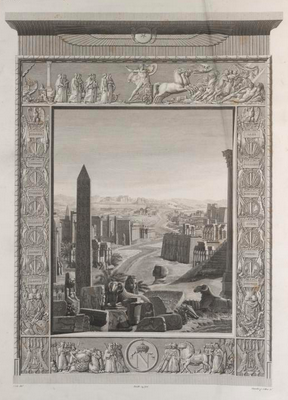

As objects of scientific interest as well as public curiosity, mummies attracted attention in Philadelphia throughout the first half of the nineteenth century, a time of increased interest in all things Egyptian following reports of the 1799 expeditions to Egypt by Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821). Physicians and medical schools added mummies to their collections of interesting anatomical specimens. In 1816, the Rev. Thomas Hall (1750-1825) gave an infant mummy and a woman’s hand to the Medical School of the College of Philadelphia. By 1821 Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) had a mummy head in his Philadelphia Museum, then located in the old Pennsylvania State House (Independence Hall).

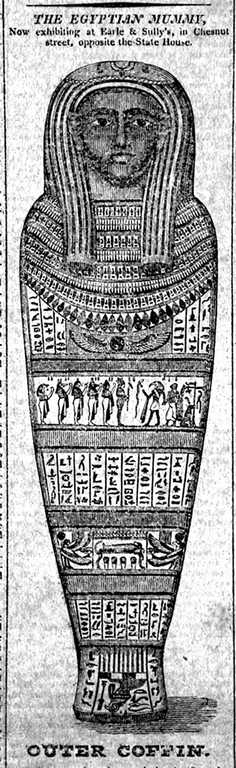

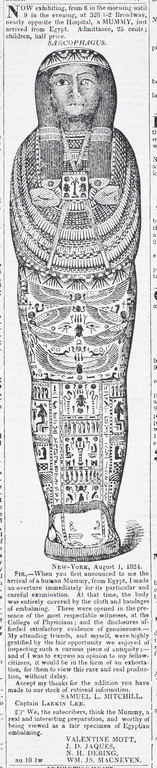

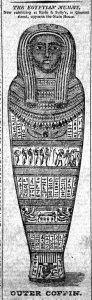

The first entire Egyptian mummy to arrive in the city was Padihershef, a mummy that had been presented to the Massachusetts General Hospital in 1823. The hospital exhibited the mummy up and down the East Coast as a fund-raiser for its dispensary, including an 1824 stop at the Chestnut Street gallery operated by artist Thomas Sully (1783-1872) and picture and frame dealer James S. Earle (1807-1879). Another Egyptian mummy, brought by sea captain Larkin Thorndike Lee (1780-1825) in 1824, made several appearances between 1825 and 1829 at the Washington and Philadelphia Museums owned by Jesse Sharples (1759-1832) at 48 and 274 Market Streets.

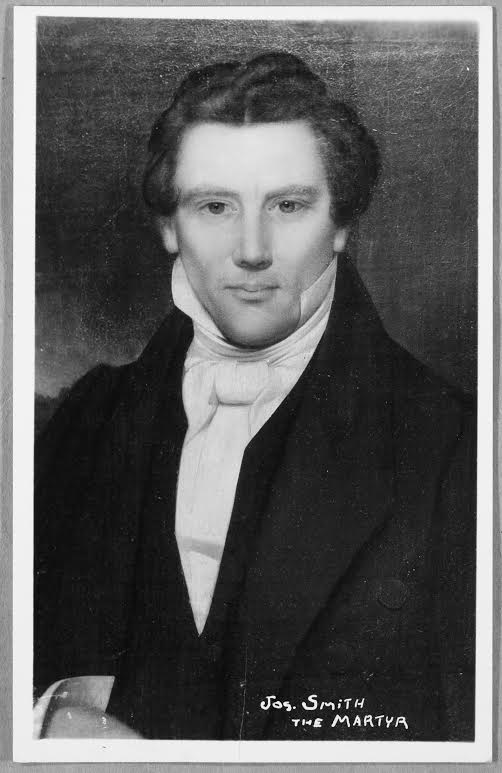

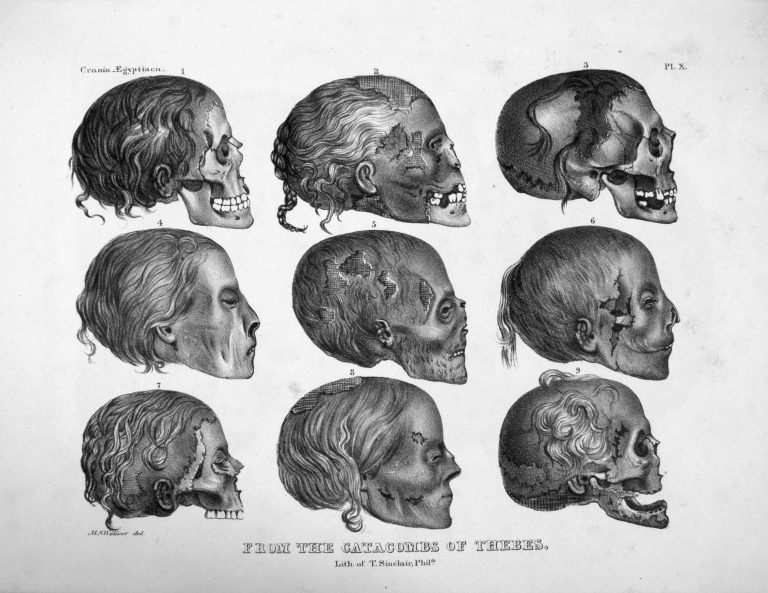

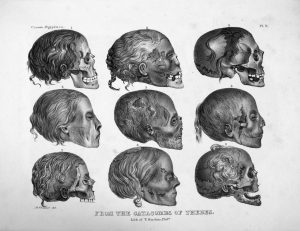

Although an 1835 decree by the ruler of Egypt, Muhammad Ali Pasha al-Mas’ud ibn Agha (1769-1849), effectively banned the export of Egyptian antiquities for the next fifty years, specimens continued to circulate. Perhaps the largest collection of mummy heads in Philadelphia was assembled by the physician and natural scientist Samuel George Morton (1799-1851), a founder of the American School of Ethnology, which promoted a theory that humans differed by species, with non-whites inferior to whites (later termed scientific racism). By 1840 he had assembled a large collection of skulls in order to support his theory of polygenesis (more than one original ancestor). Many of the skulls were contributed by Egyptologist George Robbins Gliddon (1809-57). This collection later went to the Academy of Natural Sciences, and from there to the University of Pennsylvania.

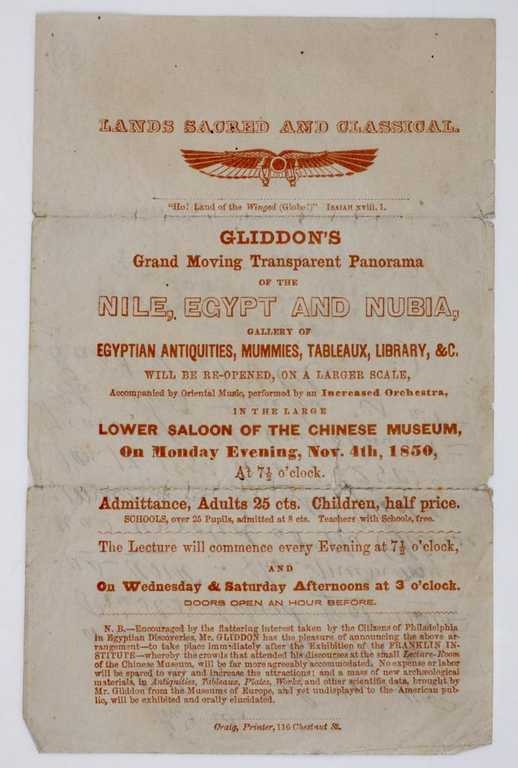

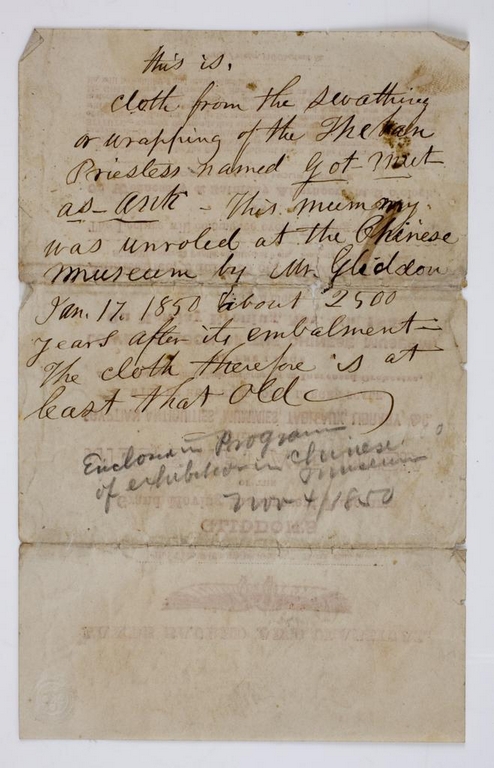

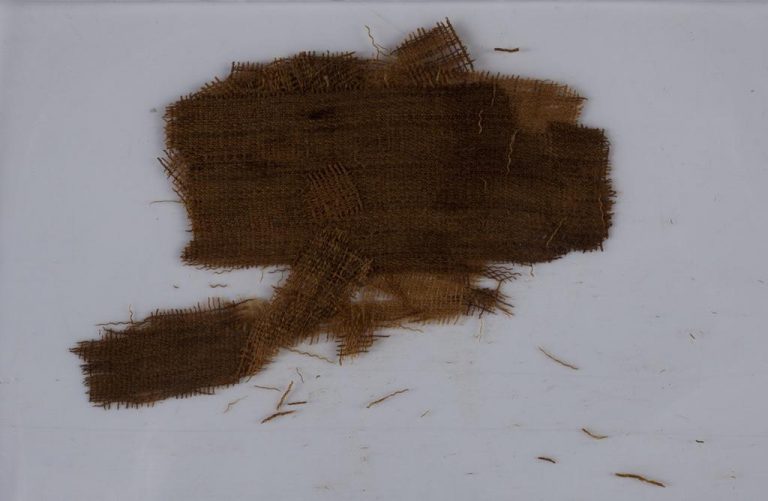

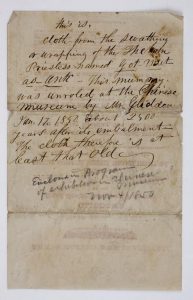

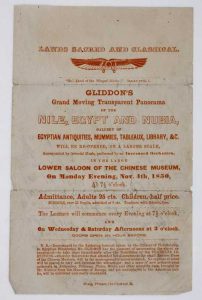

The most exciting exhibition of Egyptian mummies arrived in late 1851 when Gliddon brought his Panorama of the Nile rolling painting show and four mummies to the Chinese Museum at Ninth and Sansom Streets, after an infamous incident in Boston where he had misidentified the sex of a mummy he was unwrapping as part of the show. At Philadelphia’s Chinese Museum in 1852 he publicly unwrapped two mummies before a large audience. Bits and pieces of the mummy wrappings were preserved as souvenirs. During the exhibition, ventriloquist Signor Blitz (1810-77) caused one of the mummies to “speak” and afterwards used a mummy as a prop in his act.

The Academy of Natural Sciences, then located at Broad and Sansom Streets, soon followed with its own more sedate exhibit, displaying four human mummies: three Peruvian and one Egyptian in its original sarcophagus, which had been presented to the museum in 1846 by Philadelphia merchant James L. Hodge. The long-term exhibit, which began in 1852, also included a mummified calf, two hawks, six ibis, and thirty-two serpent mummies, all gifts from Gliddon. A mummified child from Thebes, the gift of physician John Hamilton Slack (1834-1874), was added sometime before 1858.

Additional mummies reached Philadelphia in the decades after the Civil War. During the 1870s, mummies became part of the Mutter Museum of anatomical specimens, then at Thirteenth and Locust Streets, which in 1874 received the skull collection of Viennese anatomist Joseph Hyrtl (1810-94), who was trying to disprove the popular theories of phrenology. Among the skulls were the remains of two Egyptian mummies. During the Centennial Exhibition in 1876, professor, soldier, member of the United States House of Representatives, and foreign minister Dr. Jabez Lamar Monroe Curry (1805-1923) lent a mummy to Cook, Son & Jenkins’s Work’s Ticket Office in Fairmount Park. The mummy, which Curry had obtained while on a “Cook’s tour” of Egypt, enticed visitors to book tours through Cook’s agency. In 1890, pharmacist August Hohl (1805-1908) kept a mummy in the window of his pharmacy at Front and Race Streets. (For hundreds of years powdered mummy had been prescribed for ailments, including those of the stomach, and continued to be considered to be an efficacious medicine until well into the 1900s.) Also in 1890, the Great European Museum, a “dime museum” or collection of oddities at 708 Chestnut Street, exhibited several mummies, including a hydrocephalic child.

While public fascination continued, a new era of exploration by archaeologists in the 1880s uncovered new mummies and new knowledge about them. One of the largest Egyptological collections in the United States began to take shape during the late nineteenth at the University of Pennsylvania, which formed a Department of Archaeology and Anthropology in 1887 and built a museum (the Free Museum of Science and Art, later the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology) between 1890 and 1899. At first the museum supported expeditions by the Egypt Exploration Fund (later Egypt Exploration Society) and in particular the work of British archaeologist Sir William Flinders Petrie (1853-1942). In 1902 Petrie gave the museum a mummified priest named Hapi-Men from Abydos dating to the Ptolemaic Period (30th Dynasty). He had been buried with his dog, which became affectionately known as Hapi-Puppy. Among other mummies from a variety of eras, the museum’s collections also included “Ginger,” a predynastic mummy named for the coloration that resulted from being naturally preserved in dry sand. From these beginnings and continuing into the twenty-first century, more than three hundred excavations in cemeteries, palaces, temples, towns, sanctuaries, and settlements were added to the collection.

In addition to exhibitions, the continuing study of mummies at the Penn Museum in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries used X-rays and CAT scans to reveal the bodies without disturbing the wrappings. These examinations disclosed information about sex and age as well as any evidence of illness, disease, or bone trauma. Anthropologists used these findings to better understand the lives and cultures of Ancient Egypt. Meanwhile, cleaning and restoration of mummies and their coffins preserved them as subjects of interest for the future.

S.J. Wolfe is senior cataloguer and serials specialist at the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, Massachusetts, where she has worked since 1982. She has studied Egyptian religion and culture for over sixty years, turning her research specifically on the historical aspects of the mummies as artifacts in American museums. She is the author of many articles and lectures, as well as the definitive study Mummies in Nineteenth Century America: Ancient Egyptians as Artifacts, and is the Director of the EMINA (Egyptian Mummies in North America) project and online database and the curator of the online exhibition of Mummymania in America (mummymania.omeka.net). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- Mummymania

- EMINA (Egyptian Mummies In North America)

- The Great Gliddon Mummy Unwrappings of 1850 (American Antiquarian Society Blog)

- Egypt (Mummies) Exhibit (University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology)

- Special Visitor in the Artifacts Lab (University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology)