Fashion

By Clare Sauro

Essay

Fashion played an important role in Philadelphia’s development as a center for retail and manufacturing. Philadelphians imported and promoted the latest European styles while producing garments and accessories of comparable style and quality. Area retailers played a pivotal part in fostering consumer culture in the nineteenth century and set industry standards for the nation. Despite these impressive achievements, Philadelphia was eclipsed by New York as the center of American fashion by the dawn of the twentieth century. As fashions changed and demographics shifted, the regional industry declined.

During the eighteenth century, a large population of Philadelphia merchants imported the latest luxury goods from Europe for an eager consumer market. The distinction between imported and domestically produced fashions often blurred. For example, mantua makers (dressmakers) and milliners (hat makers) imported the latest fashions and then reproduced and modified them for the domestic market. Fashionable garments had traditionally been available to only the wealthy few, but improved methods of production and distribution allowed people of all classes to participate in some way.

In the years just before and during the American War of Independence, wearing imported styles came to be seen by many as unpatriotic and frivolous. Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) strongly advocated domestic goods, for example eschewing powdered wigs for natural hair and imported silks for homespun wool as acts of symbolic and economic rebellion. Philadelphia artisans flourished during this period of non-importation, but Atlantic trade soon resumed. To compete with the allure of expensive imports, Philadelphia artisans developed a reputation for making high quality goods with sophisticated style.

Growth of Philadelphia Fashion

In the early years of the republic, Philadelphia’s Chestnut Street became recognized as one of the most fashionable retail streets in the world. Despite this reputation, the fashions worn by Philadelphians largely originated in Europe. Men’s styles derived from London’s Savile Row tailors, while women looked toward the many dressmakers and milliners of Paris. Although the silhouettes changed roughly every five years, fashionable dress for men and women settled into a system that endured well into the twentieth century. For day, a well-dressed man was expected to wear a dark suit with waistcoat (vest), crisp white shirt, polished shoes, hat, and gloves. Women were expected to wear a closely fitted floor-length dress over a corset and layers of petticoats. Like men, they accessorized their garments with a variety of collars and cuffs, shawls and mantles, gloves and a bonnet. These fashion essentials were readily available from Philadelphia artisans and manufacturers. Philadelphia tailors took an active role in improving and promoting their craft. Two notable examples were rival tailors Allen Ward (1786-1862) and Francis Mahan (c. 1790-1871), who both promoted their improved methods of pattern drafting and production through patents and publications. By the 1840s both tailors were publishing fashion plates promoting their designs.

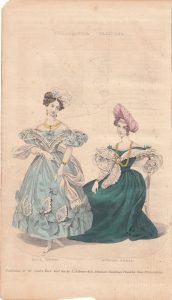

Philadelphia’s history as a center for publishing reinforced its reputation as the fashion authority of the United States. Godey’s Lady’s Book, which began publication in 1830, became famous for its hand-tinted fashion plates. These “Philadelphia Fashions” as Godey’s initially described them, often were redrawn from French originals and modified to make them suitably modest for the American audiences. Other women’s journals such as Graham’s Magazine and Peterson’s Magazine quickly followed the Godey’s formula. Philadelphia publishers also produced numerous etiquette manuals with instructions for correct behavior, including proper dress for all occasions.

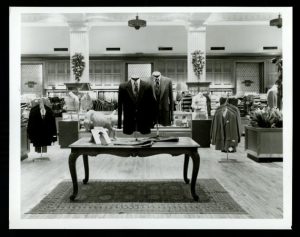

The mid-nineteenth century saw the rise of several large retail emporiums specializing in “fancy and staple dry goods,” a catchall phrase that encompassed a wide array of fashion-related items including textiles, trimming, ready-to-wear garments, and accessories. Many of these dry good “palaces,” such as Strawbridge & Clothier and John Wanamaker & Co., developed into the department stores of the later nineteenth century that sold goods ranging from fashions and home furnishings to more outrageous items such as exotic pets, fine art, and historic artifacts. John Wanamaker & Co., the best known among them, served as a national model with its innovative approach to marketing, novelty, and high style. Later in the century, these retail giants would be joined by others, most notably Gimbel Bros. and Lit Bros., who promised “hats trimmed free of charge.” Smaller cities and towns in the region had their own dressmakers, tailors, and retailers, but residents also could purchase ready-to-wear garments from the mail-order catalogues of retailers such as Strawbridge & Clothier.

Fashion Propelled Growth

Fashion played a crucial part in the growth of department stores, stimulating consumer desires for the new and novel and encouraging abandonment of items that were still functional but outmoded. To attract an elite clientele, many department stores and dry goods emporiums also offered in-house custom dressmaking and tailoring departments to lure customers away from traditional establishments. Department stores deliberately sought the patronage of female consumers and provided a safe, semi-public space for them to visit. Shopping provided an outlet for personal expression, an escape from the reality of everyday life, and an opportunity to see and be seen.

The increased availability of ready-made goods also fueled department store growth. Philadelphia and its Manufactures, first published in 1859, outlined the array of goods produced at midcentury, singling out the exceptional quality of woolen hosiery and leather shoes. Accessories and unfitted garments such as shoes, hosiery, shirts, umbrellas, parasols, collars, corsets, hats, mantles, and cloaks were all mass-produced and increasingly acceptable to discriminating consumers. Menswear, specifically cotton shirts and the newly fashionable “sack” suit, was especially well-suited to mass-production. Despite this rapid development, truly fashionable dress of the mid-nineteenth century required an impeccable fit that could only be achieved by a skilled tailor or dress-maker. Chestnut Street and neighboring Walnut Street had an abundance of dressmakers, tailors, and milliners who provided custom-made wardrobes for their clientele.

Declining Influence

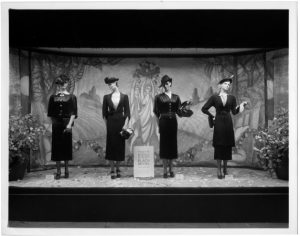

The conventions of fashionable dress remained remarkably unchanged in the early years of the twentieth century for both men and women. Suits and long dresses worn with hats and gloves remained de rigueur until the First World War instituted changes that set the tone for the next fifty years. While the silhouette varied by decade, both sexes abandoned rigid formality in favor of less-structured garments. For men, starched detachable collars were replaced by soft button-down shirts, and the top hat gave way to a variety of less formal hats such as the fedora or homburg. Active sportswear influenced the styles worn by younger men, who embraced soft caps and sweaters. Women’s clothing underwent a radical transformation; rigid corsets were abandoned, skirts shortened to around the knee, and elaborate millinery and outerwear were replaced by soft unstructured garments. Shorter skirts placed greater importance on stylish shoes and hosiery, two industries Philadelphia had long dominated.

By early years of the twentieth century, however, New York eclipsed Philadelphia as the apparel style and production leader of the United States. This had begun in the previous century after the Erie Canal, connecting the Atlantic Ocean to the midwestern regions via the Great Lakes, turned New York City into the gateway of the United States. This change in trade patterns produced a period of monumental growth for New York, earning it the nickname “The Great Emporium.” Consumers seeking the latest styles would find them in New York first, while Philadelphia became increasingly known for old money and conservative good taste. While this was not an entirely accurate assessment, plays like The Philadelphia Story (1939), with its Main Line socialite protagonist, reinforced this popular view.

By the turn of the twentieth century large department stores and specialty shops tempted consumers with a wide variety of ready-made goods and gained acceptance with the fashionable elite. Consumers were more fashion-conscious due to the emergence of fashion shows held at department stores, hotels, and private social clubs. In 1924, Rodman Wanamaker (1863-1928), the artistically inclined son of the store’s founder, purchased the Tribout Shop, a genuine Parisian store, and imported it in its entirety. For the next fifty years, the Tribout Shop specialized in exclusive European imports as well as the very best from American designers.

Stetson and Other Notable Names

Many notable names in American fashion made their homes in Philadelphia during the early years of the twentieth century. The nation’s largest manufacturer of men’s hats, John B. Stetson, occupied an impressive factory in Kensington, stretching across nine acres and producing nearly two million hats annually by 1906. Peter Thomson dominated the market for ubiquitous middy blouses and sailor dresses that were worn as school uniforms throughout the country. Jacob Reed’s Sons, a menswear manufacturer in business since 1824, flourished in this transitional fashion period and provided casual sportswear-influenced separates for generations. Philadelphia shoes retained their elite status with the designs of Laird, Schober and Company, which won numerous industry accolades and sold at retailers throughout the United States.

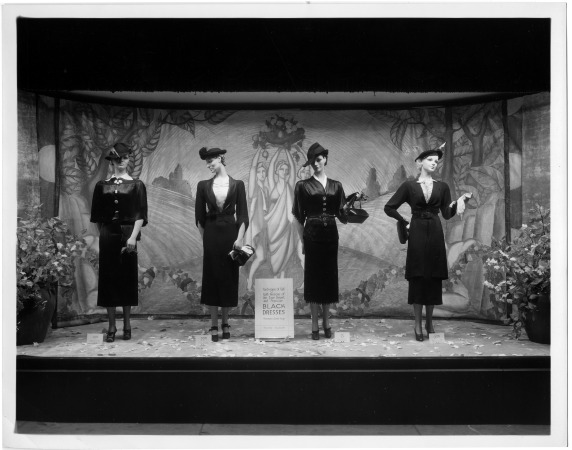

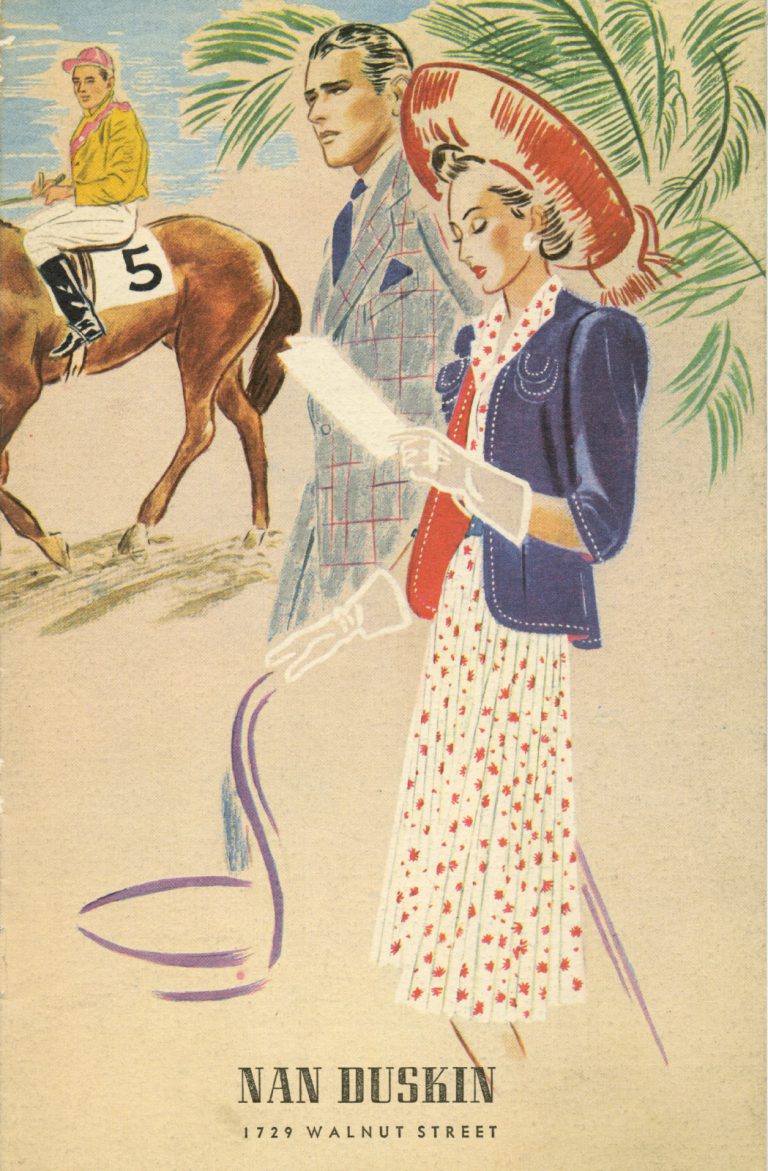

The economic collapse of 1929 had a lasting effect on American fashion, retail, and manufacturing. By 1931, French imports had dropped by 40 percent as department stores, specialty shops, and manufacturers turned to domestic talent to produce new styles. Many older stores were unable to keep afloat and were forced to close. Specialty stores like Nan Duskin and Sophy Curson, which had opened just prior to the stock market crash, defied the odds by surviving the Great Depression—a testament to the power of specialization and their knowledge of the consumer. Smaller and more focused than the larger department stores, these shops, named for their founders, could better navigate the mercurial world of high fashion. Another female entrepreneur of note, milliner Mae Reeves (1912-2016), became one of the first African American women to own her own business in downtown Philadelphia, a millinery shop opened in 1940 and remaining in business for more than fifty years.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, fashion reflected the desires of a larger suburban population and their offspring. The formality of city life was replaced whenever possible with more casual soft shirts worn without neckties and shirtwaist dresses made of new, easy-to-care-for synthetics like nylon, polyester, and acrylic. Film star Grace Kelly (1929-82) became the best ambassador of Philadelphia’s restrained style. Known as “the girl in the white gloves,” she broke the Hollywood extravagance mold with her cardigan sweaters, circle pins, and penny loafers. By the late 1960s, fashion was in even more of a state of upheaval as traditional rules of dress were jettisoned for mini-skirts, bell-bottoms, and longer, natural hair for both sexes. Even conservative dressers were forced to adapt, and fashion markets splintered into competing niche markets. Individuality triumphed over the conformity of the past, a trend that showed no sign of abating in the twenty-first century.

Retailers Follow the Fashion

As fashion changed in the 1950s and 1960s, so did Philadelphia area retailers. While the large department stores struggled in their Market Street locations and established branches in suburban shopping malls, smaller retailers such as Joan Shepp and Toby Lerner launched highly successful boutiques catering to consumers who favored easy-care sportswear and separates. During the 1980s, a series of mergers and acquisitions eventually led to the end of the many historically important stores. Gimbels closed first in 1987, followed shortly by Bonwit Teller (1990), Nan Duskin (1994), and John Wanamaker (1995). Strawbridge & Clothier held on the longest, until 2006 when it was absorbed by Macy’s.

Manufacturing in Philadelphia also mirrored changes taking place in the world of fashion. The most successful adapted to changing consumer preferences; for example, Ship’n Shore produced sportswear in easy-care fabrics, and The Villager turned out preppy styles that dominated the youth market of the early 1960s. Despite these success stories, garment manufacturing declined with prominent makers like Botany 500 declaring bankruptcy and Stetson relocating to Missouri. Swimming against this tide was Albert Nipon, a Philadelphia-based manufacturer who dominated the dress market during the 1970s and 1980s and built a $60 million-a-year fashion empire before declaring bankruptcy in 1988. Although no longer a global center of manufacturing, the Philadelphia region remained headquarters to several prominent fashion companies such as Lily Pulitzer, Destination Maternity, and Urban Outfitters.

Philadelphia has produced several historically significant fashion designers including Coty American Fashion Critics’ Award winners Tina Leser (1910-86), known for her globally-inspired sportswear; Gustave “Gus” Tassell (1926-2014), whose sleek designs were favored by Jackie Kennedy; James Galanos (1924-2016), most famous for his designs for Nancy Reagan; knitwear designer Adrienne Vittadini (b. 1945); and Willi Smith (1948-87), one of the most successful African American designers of the twentieth century. Others with strong Philadelphia ties have included Main Line-born Tory Burch (b. 1966 ), two-time Project Runway winner Dom Streater (b. 1988 ), and Ralph Rucci (b. 1957), the first American designer in over sixty years to be invited to show in Paris by the French Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture. Only two of these successful designers studied fashion at Philadelphia Schools: Adrienne Vittadini (Moore College of Art and Design) and Willi Smith (University of the Arts). The majority studied in New York, a reflection of the dominance of New York in the fashion industry.

Philadelphia has been associated with fashionable goods since the mid-eighteenth century, when artisans used style to compete with European imports. Manufacturers, publishers, and retailers continued to emphasize high style and set trends throughout the nineteenth century. However, in the twentieth century Philadelphia’s authority as a fashion center faded as trade and manufacturing moved to other regions.

Clare Sauro is Director and Chief Curator of the Robert and Penny Fox Historic Costume Collection at Drexel University. She holds an M.A. in Museum Studies: Costume and Textiles from the Fashion Institute of Technology. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- A banner day for fashion in Philly (WHYY, June 7, 2011)

- Philly and fashion go global (WHYY, August 1, 2012)

- Philadelphia University students debut end-of-year fashion collections (WHYY, April 29, 2014)

- To become a fashion hub, Philadelphia must retain its talent (WHYY, November 5, 2015)

- Philadelphia in Style: A Century of Fashion at the Michener (WHYY, March 15, 2016)

Links

- A More Balanced History of Rittenhouse Square (PhillyHistory Blog)

- Robert and Penny Fox Historic Costume Collection

- Fashion and Family Photographs (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Philly Fashion Week

- The Generations Collide On Fabric Row (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Stetson Hats: the western icon made here (Philly History Blog)