Artisans

Essay

As skilled laborers who hand-crafted their goods on a per-customer basis, artisans played a central role in the formation of Philadelphia’s prerevolutionary economy: producing essential goods and services and providing social stability within households composed not just of immediate family but also of journeymen and apprentices. American independence brought artisans new economic opportunities as the city expanded and new markets emerged. With the maturing of a market economy, however, artisans, and journeymen in particular, faced the loss of both social and economic status as the economy that supported such work became more volatile and contentious.

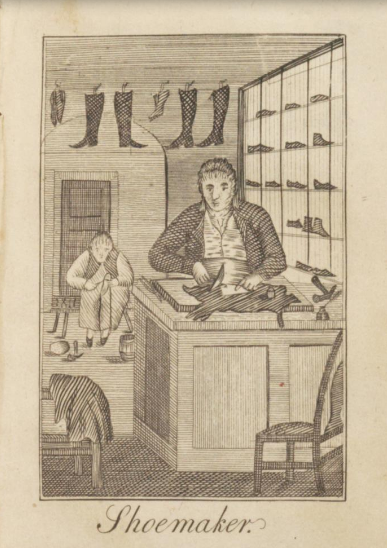

During the early colonial period, up until the mid-1760s, the town economy of Philadelphia built on the contributions of artisans and entrepreneurs. Artisan shops produced shoes, soap, wagons, clothes and food for the town, while also laying bricks and constructing buildings. By 1745, master artisans made up 48 percent of the total population of Philadelphia, highlighting their significance to the burgeoning town. For artisans of this period, the home and workshop were very often in the same building or at the least in close proximity. In some cases, master artisans labored alone to complete specific orders for their customers, but in many cases they relied on the work of indentured servants, slaves, and a few skilled journeymen to assist in the completion of their tasks. Master artisans were respected throughout the city, due in large part to the vital goods they provided the community, but also for the independence of their craft.

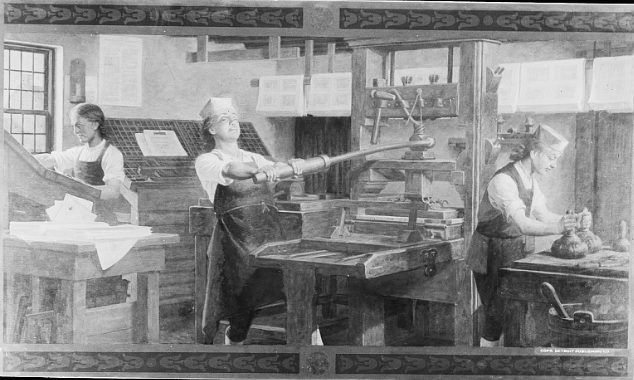

By the end of the Seven Years’ War (1754-63) the labor market had changed dramatically to favor free laborers over indentured servants, whose availability had declined. Typically, then, master artisans owned the shop, ordered supplies, supervised the workers, and continued to work alongside his employees, including apprentices and journeymen. Apprentices were traditionally teenagers who spent three to seven years learning their craft under their masters, from whom they could expect room, board, and education. Between the ages of eighteen and twenty-one they would be promoted to journeymen status, given a set of tools, a suit, and a wage. Journeymen were skilled workers who performed their work with little interference from the master and received pay by the day or by piece. Tradesmen viewed this system of labor as a type of fluid hierarchy in which apprentices would someday climb the artisanal ladder, from journeymen to master and proprietor of their own shops.

Masters, Journeymen, Apprentices

The relationship between master artisans, journeyman, and apprentices was initially built on mutual respect, and master artisans took a paternal role over their laborers. Work was performed at a casual pace and on a per customer basis. Workers wore leather aprons, shared workbenches, and worked with hand tools to construct their goods. The workday was long, traditionally twelve to fourteen hours, but consisted of morning breaks for coffee and beer, a lunch break in the early afternoon, and a late afternoon break for a snack. Overall, artisans within Philadelphia strove for “competence,” the ability to provide enough money to support their families and save a little for the future, but few master artisans were actually able to reach this level of economic comfort.

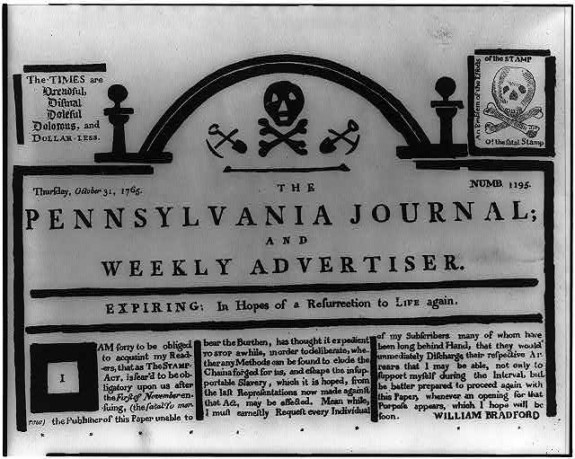

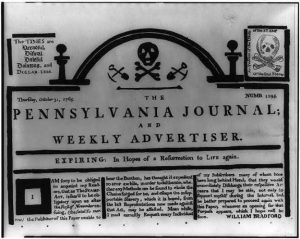

The end of the Seven Years’ War also brought implementation of imperial acts by Britain on the colonies. These acts served as a blessing for many struggling Philadelphia artisans because many of them did not tax home-produced goods. As Philadelphians used the policies of nonimportation, or the boycotting of British goods, in the years leading up to the American Revolution, the purchase of home-produced goods brought increased business to Philadelphia artisans. Nonimportation pitted artisans against merchants who benefited from Atlantic trade with Britain, but these differences were largely cast aside once war broke out. During the War for Independence, Philadelphia artisans enjoyed a period of production with little competition. This did not last long, for when the war ended and Atlantic trading resumed, artisans found themselves once again competing against foreign goods. During the postrevolutionary years, they joined merchants in seeking a stronger central government that would protect the nation’s domestic industries.

Dramatic Shifts After the Revolution

The postrevolutionary years also brought dramatic shifts to the relationship between master artisans, journeymen, and apprentices. By the 1780s masters no longer signed contracts with apprentices promising tools, clothes, or an education, but instead replaced these items with monetary compensation. Masters refrained from teaching apprentices the art of the craft and instead tended to rely on them as simple wage laborers. The increased presence of under-trained workers within their craft angered many journeymen, as did other changes within their labor environment. As work customs changed to meet new market obligations, such as fewer breaks, more oversight, less autonomy at work, and decreased wages, journeymen perceived their interests diverging from that of their masters, and they began to doubt their ability to climb the artisanal ladder. Such changes strained the relationship between masters and journeymen. Perceiving master artisans as no longer producing for a community, fulfilling their paternal obligations, or striving to reach “competence,” journeymen came to view their master’s intentions as a threat to the social and economic order of society and at odds with the true and moral intentions of labor.

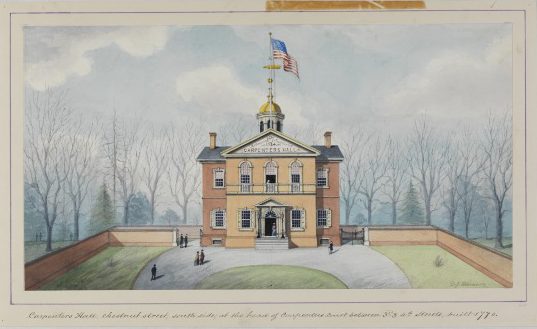

The first sign of dissension emerged in 1786 during one of the nation’s first strikes—the first recorded strike in Philadelphia’s history—as journeymen printers went on strike against employers refusing to pay a weekly rate of six dollars. Further divisions became apparent during the 1788 Federal Procession, which honored the ratification of the U.S. Constitution, when at least two trades marched in separate companies, one of master artisans and one of journeymen. By the 1790s early labor disputes between these two groups sprung up in a number of crafts, including carpenters in 1791 and cabinetmakers in 1795. Tensions between these two groups continued after the turn of the century as revolutions in transportation, communication, and industrialization greatly expanded the market economy well beyond Philadelphia, giving priority, in the eyes of journeymen, to the market over the moral intentions of craft labor.

While artisans played a significant role in crafting Philadelphia’s colonial and pre-Revolutionary economic and social history, divisiveness within artisanal ranks also played a large role in shaping Philadelphia’s post-Revolutionary history. As markets continued to expand throughout the first half of the nineteenth century, the divide between master artisans and journeymen grew. Many master artisans left the workshop and became simply business owners, merchants, and entrepreneurs. Journeymen continued to toil in the workplace, but it was as wage laborers, and work was most likely performed at a machine and no longer at a workbench. As friction between these two developed into the 1820s journeymen laborers responded with the formation of trades unions and political parties to fight their cause, which set up a nearly thirty-year period of labor and class unrest within Philadelphia.

Patrick Grubbs is a Ph.D. candidate at Lehigh University who is writing his dissertation entitled “The Duty of the State: Policing the State of Pennsylvania from the Coal and Iron Police to the Establishment of the Pennsylvania State Police Force, 1866 – 1905.” He has been employed at Northampton Community College in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, since 2009 and has taught Pennsylvania history there since 2011. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- Disruption of the Artisan System of Labor (Digital History, University of Houston)

- Labor's Struggle to Organize (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Address to the Journeymen Cordwainers, by John McIlvaine. Philadelphia, PA, 1850. (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Benjamin Franklin and Apprenticeship in the 18th Century (PDF, Historical Society of Pennsylvania)