Hat Making and Millinery

Essay

Hat making, among the earliest occupations in Philadelphia, grew to be one of the city’s major industries. It was especially robust in the late nineteenth through mid-twentieth century, when Philadelphia was home to dozens of hat factories, including the world’s largest hat manufacturer. Millinery, the making of women’s hats, did not reach the same level of mass production, but also became a longtime viable industry in the region. Hat making—for men, done by “hatters”—and millinery—for women, done by “milliners”—were, for the most part, different professions that used different materials and production techniques, although at times they overlapped. Millinery also sometimes encompassed making or selling women’s apparel accessories and fabrics.

In early America, hats were generally made of felted beaver fur, although wool, straw, and other animal skins were also used. The first hat makers on record in Philadelphia were John Colley and Anthony Sturgis, each listed as a “hatter and felter” in a 1690 description of businesses in Philadelphia. In 1698, the author of An Account of Pennsylvania and West Jersey noted that “Felt makers will have for their hats seven shillings apiece, such as may be bought in England for two shillings apiece.” Labor was in short supply in America as compared to England, resulting in higher prices for domestically made goods.

Dozens of hat makers worked in Philadelphia in the eighteenth century, as recorded in account books, tax records, and city directories. Early Pennsylvania statesman and scholar James Logan (1674-1751), heavily involved in the fur trade, supplied beaver pelts to a number of local hatters in the 1710s and 1720s, while cabinetmaker John Head (1688-1754) made hat blocks for several Philadelphia hatters in the 1740s, including his son John Head Jr. (1723-92) and two of his sons-in-law, Jeremiah Warder (1711-83) and Benjamin Hooton (1719-93). Around 1800 hatter Benjamin Cresson (1774-1827) advertised that he had “commenced business at the house formerly occupied by his grandfather, Benjamin Hooton, 14 North Second Street, four doors below [Christ] Church, where he has for sale an assortment of beaver, castor, roram, and wool hats.” Another hatter in this period, Isaac Parish (1735-1826), had his shop across the street from Cresson, at 17 N. Second Street.

In 1802, 102 hat-making workshops operated in Philadelphia. Most hatters in this period, like Cresson and Parish, were artisans who made hats by hand in shops in their residences. This began to change over the course of the nineteenth century, as industrialization brought large-scale, factory-based production to the hat-making industry. In 1823 John Fareira opened one of the earliest hat factories in Philadelphia at Front and Spruce Streets. Originally a small operation, with just Fareira and four workmen, the company grew and moved to a four-story building on Lombard Street west of Tenth Street, with a separate finishing shop and store at 25 N. Front Street. As in other industries, artisans continued to make hats by hand, but they increasingly competed with factories that produced hats in large quantities.

Millinery Evolution

Millinery developed more slowly than hat making and remained mostly a small-scale, artisan-based industry, practiced almost exclusively by women. In 1773 Lydia Whitehead was indentured to Mary Brown “to be taught the trade of bonnet, hat and cloakeing making.” In 1784 Frances Rugge announced in the newspaper that she was a milliner from London who recently opened a shop on Market Street below Water Street “near the wharf,” where she offered a variety of women’s apparel, including “hats, bonnets, etc. of the newest fashions.” In 1788 Jane Gee announced that she had recently moved her shop to the northeast corner of Second and Chestnut Streets, where she offered “a variety of Millinary [sic] ready made” as well as “a quantity of hat and bonnet wires, of the newest fashions.” City directories reveal significant growth of the profession in the early nineteenth century, listing only one milliner in 1800 (as compared to fifty-three male hatters that year), but thirty-nine in 1820 and more than 160 by 1850, almost all women. While some of these milliners may have been shop owners who just sold goods rather than producing them, and others may have focused more on apparel than hats, millinery was a viable profession for women in the nineteenth century.

Millinery was practiced by African American women as well. Grace Bustill (later Grace Bustill Douglas, 1782-1842), daughter of Cyrus Bustill (1732–1806), ran a Quaker millinery shop and, like her father, was a leader of Philadelphia’s African American community. Sarah Eddy, the daughter of noted pastor Richard Allen (1760-1831), founder of Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, also worked as a milliner and dressmaker. Seven free Black women worked as milliners in 1838 (as did four Black male hatters that year), while in 1856 forty-five Black women worked as milliners and dressmakers and three others combined millinery with other apparel making.

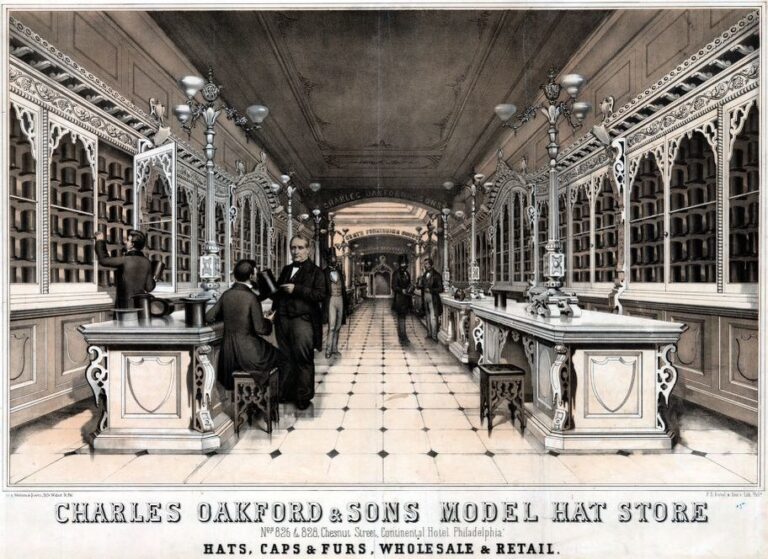

Large-scale hat manufacturing had taken hold in Philadelphia by this time. The factories of William Beard (d. 1861) at 822 N. Lawrence Street in Northern Liberties and P. Herst & Co. at 36 S. Fifth Street in Old City had 180 and 150 employees, respectively, in 1857. Herst, founded in the early 1840s, was an early manufacturer of silk hats, which in the mid-nineteenth century began to rival the fur hat in popularity among style-conscious men. Hat makers with facilities in the heart of Philadelphia’s commercial district that served as both factories and retail stores included C. H. Garden & Co., on Market Street above Sixth Street; the New Hat Company on the northeast corner of Sixth and Chestnut Streets; and Charles Oakford’s (1830-1906) Model Hat Store, on Chestnut above Sixth Street. Oakford’s was one of the city’s most fashionable stores.

Hat making in general had become rather specialized by the mid-nineteenth century, with certain factories focused on making hat bodies and others on the finishing work. “Outwork”—in which men shaped hat bodies at home and returned them to the factory for finishing—was part of the manufacturing process as well. (Outwork was a common practice in certain Philadelphia industries in the nineteenth century, particularly textiles and apparel.) Notably, the vast majority of pelts used in local hat making at this time were imported, as extensive fur trapping had seriously depleted the American beaver population. Straw hats were also made in quantity in Philadelphia, sold locally for wear in warmer weather and distributed for sale in the American South.

Hats of Fur and Felt

A series of industrial surveys of Philadelphia manufacturers in 1874 documented the city’s largest hat makers at the time, including the makeup of their workforces. E. Morris & Co. made both silk and felt hats at its large factory near Third and Spruce Streets, which employed two hundred workers: 130 men, fifty girls, and twenty boys. The Gibb & Walton Hat Factory on Lawrence Street near Brown Street in Northern Liberties, makers of fur hats and bodies, had 180 employees: 150 men, eighteen girls, and twelve boys. And P. Herst & Co., which had relocated to a complex of buildings in a courtyard near Second and Arch Streets and shifted its focus to felt hats, had 120 workers: eighty-three men, thirty-three girls, and four boys. John Fareira’s hat factory—which became Joseph Fareira & Sons after Joseph Fareira (b. 1811), son of the company founder, took over the business in 1832—focused on felt hats, with eighty workers in 1875, including women who did specialized finishing work.

Philadelphia’s hat-making sector underwent significant geographic expansion at this time. The small artisan shops of the eighteenth century and early hat factories of the first half of the nineteenth century operated mostly in and around the downtown area. While some factories remained in this section, most large-scale hat manufacturing in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries took place in the increasingly industrialized areas north of the city center, in neighborhoods such as Callowhill, Northern Liberties, North Philadelphia, and Kensington.

The 1870s saw the rise of the company that became the world’s largest hat maker and one of Philadelphia’s industrial giants: the John B. Stetson Company. John B. Stetson (1830-1906) was born into a family of hat makers in Orange, New Jersey, one of the nation’s early hat-making centers. He learned the trade and then as a young man traveled in the American West, where he noted that most men’s hats were of poor quality and ill-suited to the rugged climate. After returning home, in 1865 Stetson rented a room at Seventh and Callowhill Streets in Philadelphia and started a small hat-making operation, eventually focusing on making fine quality felt hats for the western market. The business prospered, and in 1874 Stetson moved to a new factory at Fourth Street and Montgomery Avenue in Lower Kensington, which grew over time into a sprawling twenty-five building complex. At its height in the early twentieth century, Stetson employed some 5,400 workers.

Stetson made many kinds of hats—felt, straw boaters, derbies, military headwear, high-fashion millinery—but was best known for the “Boss of the Plains,” the iconic ten-gallon cowboy hat that John Stetson himself invented. Introduced in the early 1870s, the wide-brimmed, felt hat with a high crown proved immensely popular; it was worn throughout the American West, seen in countless cowboy movies, and used by the United States and other nations’ militaries.

Stetson’s Production Depth

Stetson was unique among Philadelphia hat manufacturers in that it was a “vertically integrated” operation: all hat-making functions were performed within the company—from processing animal pelts to making ribbons to manufacturing the signature boxes in which its hats were packaged. Whereas most hat makers relied on specialty companies for many of these functions, Stetson did them all in house. John Stetson also became known for his benevolent, paternalistic approach to his workers. He established a school, hospital, building and loan association, and other support services for his employees and the Kensington community. While charitable, these acts were likely also part of Stetson’s effort to prevent unionization of his company.

Stetson’s dominance notwithstanding, many other hat makers were active in late-nineteenth and early twentieth-century Philadelphia. Sixty-six makers of men’s and boy’s hats operated in the city in 1883, employing a total of 1,793 workers: 1,007 men, 465 women, and 321 boys and girls. In addition, 125 companies specialized in specific aspects of the industry, either in making other types of hats, such as bonnets or straw hats, or in related functions such as trimming hats or making hat bodies or frames. Among the larger traditional Philadelphia hat makers at the turn of the twentieth century—all dwarfed by Stetson—were Frank Schobel & Company in North Philadelphia; Eli Keen’s Sons in Old City; Price, Sherman, & Co. in South Philadelphia; Henry H, Roelofs & Co. in the Poplar neighborhood of North Philadelphia; and Joseph F. Wittman, which in 1919 merged with a New York City firm to form Wittman-Moriarity, with manufacturing facilities in Kensington. Two hat factories opened in the Callowhill neighborhood in the 1920s: S & S Hats at Twelfth and Wood Streets in 1923 and Frank P. Heid & Co. at Thirteenth and Callowhill Streets in 1927.

The local millinery profession continued through the twentieth century, still on a mostly small scale. African American women in particular were known for their millinery shops. The Philadelphia Colored Directory of 1907 listed two milliners—Mrs. F. B. Curtis on N. Perry Street in North Philadelphia and Mrs. J. H. Morris on S. Nineteenth Street in South Philadelphia—although there were likely many others. The city’s most famous twentieth-century African American milliner, Mae Reeves (1912-2016), moved to Philadelphia from her native Georgia in 1934, found work in a clothing store on South Street, and eventually opened her own hat shop at 1630 South Street in 1942, before moving in 1953 to 41 N. Sixtieth Street in West Philadelphia. Reeves made hats for local customers as well as socialites and celebrities—Black and white—for fifty-five years, until her retirement in 1997. Her shop was later recreated in the permanent Mae’s Millinery Shop Exhibit at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Decline of Men’s Hat-Wearing

The Philadelphia hat making industry declined dramatically in the post-World War II period, part of a broader deindustrialization of the region brought on by a number of factors: cheaper labor and energy costs in other parts of the nation and world, competition with cheaper goods made elsewhere, and conflicts between labor and management. A key factor in the decline in hat making specifically was that men stopped wearing hats for the most part. Whereas a hat had long been an essential part of male attire, this began to change in the mid-twentieth century. Fashion experts point to the fact that President John F. Kennedy (1917-63) did not wear a hat for his inauguration speech in January 1961—the first U.S. president in memory not to do so—as a signal moment in this development. The combination of changing fashions and broader economic forces spelled the end of hat making as a major Philadelphia industry.

Almost all of the city’s large hat manufacturers moved or went out of business in the late twentieth century. Stetson, after 106 years in the city, closed its Kensington factory in 1971 and moved its operations elsewhere, eventually settling in Texas, where it still made hats in the early 2020s. The loss of such a major employer, together with the closing of dozens of other factories in the area, had a devastating impact on Kensington, one of the neighborhoods that bore the brunt of Philadelphia’s late-twentieth century deindustrialization. While virtually all of the buildings in the massive Stetson complex were later demolished or destroyed by fire, the hospital building survived on North Fourth Street, occupied in the early 2020s by a vocational and human services organization.

Small millinery shops continued to operate in the region in the early twenty-first century, while one longtime Philadelphia factory that made women’s headwear had a bit of a resurgence: S & S Hats, which had been in business since 1923 and had moved from Callowhill to a factory on Fraley Street in Bridesburg, was on the verge of closing when the Reverend Georgiette Morgan-Thomas (b. circa 1949), of Harlem, New York City, purchased the company in 2015. Morgan-Thomas renamed the business American Hats LLC and continued its focus on making stylish women’s hats. With about twelve employees in 2019, American Hats was tiny in comparison to the huge hat manufacturers of Philadelphia’s industrial heyday, but it represented a continuation of the city’s rich tradition of hat making, especially African American millinery.

Jack McCarthy is an archivist and historian who specializes in three areas of Philadelphia history: music, business and industry, and Northeast Philadelphia. He regularly writes, lectures, and gives tours on these subjects. His book In the Cradle of Industry and Liberty: A History of Manufacturing in Philadelphia was published in 2016, and he curated the 2017–18 exhibit Risk & Reward: Entrepreneurship and the Making of Philadelphia for the Abraham Lincoln Foundation of the Union League of Philadelphia. He serves as consulting archivist for the Philadelphia Orchestra and Mann Music Center and directed the 2018-2019 project Documenting & Interpreting the Philly Jazz Legacy, funded by the Pew Center for Arts & Heritage. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2022, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Stetson: Made in America for 150 Years (2015, Youtube)

- Stetson Hats: The Western Icon Made Here (PhillyHistory Blog)

- Mae Reeves Millinery Shop (Youtube)

- Stetson Hat Company Site (PhilaPlace)

- Millinery Shops in 18th-Century Philadelphia (Southwark History)

- Hats Off to Mae Reeves! (National Museum of African American History and Culture)