Zoning (Philadelphia)

Essay

From its inception, zoning became a fraught subject. By empowering neighborhood groups and local politicians with power over land use in their communities, zoning brought such groups in Philadelphia and elsewhere into contest with developers, industrial concerns, and sometimes with other people who wanted to move into their neighborhoods. The policy generated results both noble, like removing noxious industrial development from residential areas, and vicious, when it was used as a means to prevent African Americans and lower classes from moving into wealthier and whiter areas. In its multiple uses, zoning helped determine what jurisdictions were and what they could become.

Zoning emerged first in early twentieth century New York, although West Coast cities began experimenting with the concept a few years earlier. The purpose of the new policy was to allow local governments to control land use, a marriage of Progressive Era good government ideals and a conservative effort to protect the interests of the upper classes and business owners. Zoning proponents did not want “incompatible” uses (industrial or cheap housing) or certain people (of lower classes and non-white races) in close proximity to their homes and businesses.

By the early 1920s residents in the neighborhoods to the west of the University of Pennsylvania were gathering for meetings about the application of zoning in West Philadelphia in response to high-rise development. At the same time, many of Philadelphia’s inner-ring suburbs—from Lower Merion Township in Montgomery County to Springfield Township in Delaware County—began to consider zoning for fear of increased density and the possibility of new working class—and possibly non-white—neighbors. (These areas of early suburban development were of a density unusual to later suburban developments and confronted many of the same dynamics as the city itself, albeit on a smaller scale.)

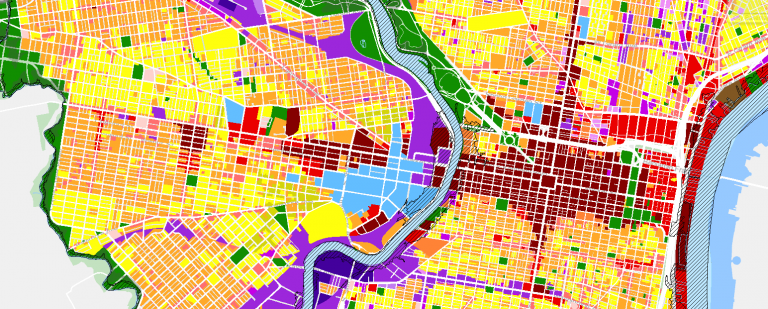

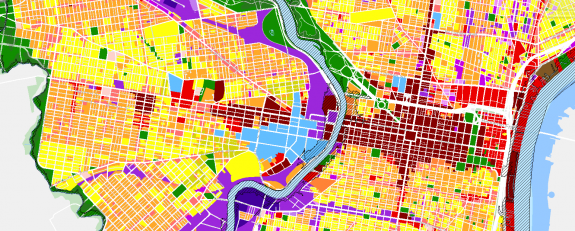

Block-by-Block Zoning Maps

Philadelphia’s original zoning code created a series of residential, commercial, and industrial classifications that largely accorded with the existing built environment. In the beginning, there were twenty different zoning districts, including nine residential, four commercial, and a variety of other uses, including shopping centers and park land. Block-by-block zoning maps were established along with the ordinance. Because the types of residential zoning were relatively few—today there are over twenty—multifamily housing was not often entirely zoned out of neighborhoods as it was in the suburbs. But these building types had to conform to the typology of the surrounding buildings and meet requirements for air and light—which often prevented the construction, for example, of, large apartment buildings in rowhouse neighborhoods.

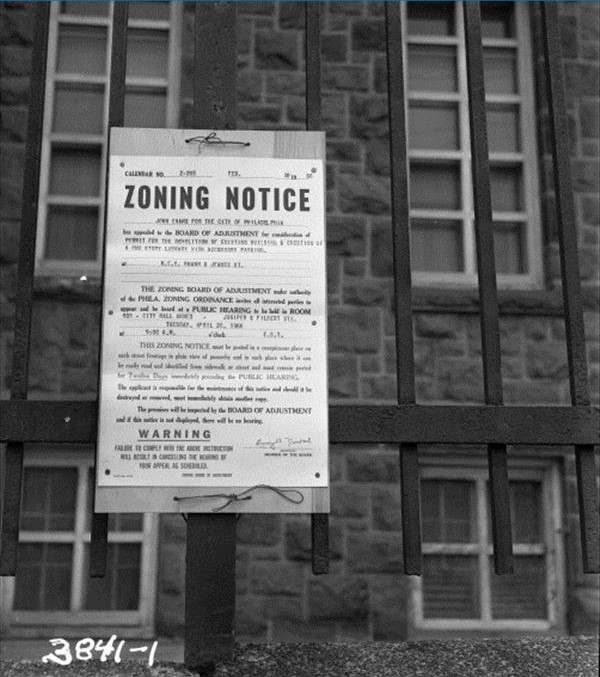

Under the code, any new building constructed in the city, or any substantial alterations to old buildings, first required the developer to obtain a zoning permit. If the project accorded with the zoning map, then the permit was granted and allowed to proceed. If the request for a permit was denied because it did not accord with the specifications of the ordinance, the applicant could appeal to the Zoning Board of Adjustment (ZBA).

The ZBA was comprised of five members, appointed by the mayor. Philadelphia’s ZBA was meant to consider appeals to the code. These were only to be granted if “a literal enforcement of the provisions of the ordinance will result in unnecessary hardship.” (Such bodies were a common aspect of zoning codes because they allowed such ordinances to avoid a full-on clash between the police powers of the state and the rights of property owners.)

Because the zoning code became a site of contest from the beginning, Pennsylvania courts were forced to make a series of rulings to clarify the ordinance. These rulings established (among other things) that variances could only apply to an area limited to a parcel.

By the mid-1950s, less than three decades after the creation of the code, the ZBA was swamped by requests for variances. With only two inspectors employed to enforce the code in a city of over two million, many cases simply resulted from inadequate code enforcement. Often property owners who had been unaware that they were violating the code applied for variances once they found out.

Lawyers in Zoning

Zoning lawyers became increasingly important in the process starting in at least the 1950s. It became clear that applicants could use the legal assistance because “a large number of applicants have no conception of what the term unnecessary hardship implies,” a University of Pennsylvania Law Review analysis reported.

Mayor Richardson Dilworth (1898-1974) and master planner Edmund Bacon (1910-2005) were proponents of a zoning overhaul, and in 1962 they helped effect a major overhaul at the tail end of a seismic era of change in the city’s government and its planning apparatus. Those changes, which no doubt stemmed in part from the staggering number of variances, drew more broadly from the work of Democratic reformers who overthrew the moribund Republican political machine and installed a suite of reforms that included a new city charter and a civil service regimen for much of the bureaucracy. The utility of the zoning code reform of 1962 was rapidly sapped, however, as the political-economy of the city changed radically in the subsequent 20 years, making it the last meaningful revision until the code was overhauled under Mayor Michael Nutter (b. 1957) in 2012.

In many ways, postindustrial Philadelphia turned out to be a dramatically different place than anyone had predicted in the early 1960s. Many of the row-house neighborhoods were originally zoned to allow multifamily housing because it was believed the city would continue growing beyond its 2.1 million people. Instead, that turned out to be the peak of Philadelphia’s population, and developers proposed few multifamily housing projects as more housing demand shifted to the suburbs. Industries were fleeing the city too, leaving much of Philadelphia’s residential and industrial zoning out of sync with shifting construction demand.

Over one thousand changes were made on an intermittent basis, expanding the zoning code from a relatively slim volume into a vast tome. New tweaks included the creation of new residential districts for uses like trailer parks and more accommodating parking in commercial and residential zones as cars became more common. The only major alteration after 1962 was a major 1988 plan to overhaul the zoning for Center City alone, which perhaps helped account for the rapid redevelopment and rebirth of downtown in the 1990s and 2000s.

The stultifying nature of the rest of the code acted to repress development in the city. Much of the language was archaic, complex, and highly specific. (There was, for example, a provision that allowed the construction of a factory that made rigatoni, ravioli, and spaghetti but not angel hair pasta.) As the code became more complex, and its content was not altered to fit a changing world, developers had to turn to the ZBA more frequently to get their projects done. By the 1990s and 2000s, anywhere from 40 to 60 percent of development projects required a variance and a trip to the ZBA.

When Council Intervenes

More rarely, developers with political influence turned to City Council for spot zoning bills, which would legislatively change the zoning of a parcel to fit the developer’s needs—sparing them a trip to the ZBA. This kind of narrowly cast legislative remapping thus long proved controversial because it was by nature a small-scale and imprecise action to change zoning reactively to accommodate a particular project and not proactively as part of a larger public-minded vision for the future. Although it was technically illegal, adroit politicians could usually get around that by remapping some surrounding parcels as well. This approach contrasted with legislative remapping supported by the Planning Commission, which was often crafted with input of the community, local politicians, and other interests over a months-long open and democratic process.

Political tampering with the zoning code led to further pressure for change. Many good-government advocates and urban experts argued that spot zoning undermined the spirit of the larger zoning code, empowered the politically connected, and incentivized corruption (or at least its appearance). In 2007, the head of the University of Pennsylvania’s Penn Praxis, Harris Steinberg, argued that zoning reform was needed to cut down on this kind of legislative remapping, arguing, “It keeps the development world in a constant state of guessing, encourages backroom deals, and keeps community groups on the defensive to protect their little piece of earth.”

As frustration with the code grew in the first part of the twenty-first century, reformers sought to align the code with “smart growth” best practices, including incentives to create density around transit hubs and other central locations, while also simplifying it so that fewer variances or legislative work-arounds would be required. Councilman Frank DiCicco (b. 1946) proved an influential backer of zoning reform, introducing legislation to establish a Zoning Code Commission and convincing Mayor John Street (b. 1943) to sign it despite his skepticism. DiCicco’s support was the result of his stewardship of a district that included swaths of Center City, the southern river wards, and South Philadelphia east of Broad Street—where much of nascent development pressure was concentrated—so he was able to witness just how obtrusive the zoning code had become.

Zoning Revision Begins, 2007

In 2007 Michael Nutter, a City Council member running as a reform candidate for mayor, bested many other better-established political figures in the race. That same year voters approved the creation of DiCicco’s Zoning Code Commission to study potential reforms to the code. The process of revision took years, involving an intricate series of public meetings and behind-the-scenes negotiations. But despite the political machinations involved, the scale of public input was impressive and impossible to imagine at any point in the twentieth century.

It took four years, but the new code was crafted with the intent of making the language much more simple and general. The reformers tried to avoid the highly specific and quickly outdated alterations that cluttered up the old code. This was partly accomplished by codifying more of the language in charts, which were easier to read and more condensed. The end result reduced the code from seven hundred to four hundred pages.

In 2011, City Council passed the new zoning code and Mayor Nutter signed it into law. (There was a built-in delayed start of nine months, so it went into full effect in August 2012.) The reformers succeeded in making it easier for new development in the city to be denser and less vehicle-focused. Parking requirements for residential projects were lessened and, in some districts, done away with entirely. The square footage of the minimum allowable lot sizes for new row houses dropped dramatically to allow smaller and, therefore, more affordable housing. It was also made easier to build new, smaller units in existing buildings. Garages that fronted on sidewalks were made more difficult to obtain as well, safeguarding the pedestrian environment, while a new process called Civic Design Review was implemented to guide better building practices. With that change, major projects could trigger Civic Design Review, bringing developers before a board of experts for advice, although the process had no binding power.

In advance of the new code, the Philadelphia City Planning Commission crafted a new comprehensive plan for the city dubbed Phila2035. They then began drafting new district plans, which were also shaped by public meetings and civic engagement, for every area of the city. These offered recommendations for redoing zoning maps, which could then be taken up in City Council. Because these efforts depended on the assent of individual council members, some areas did not adopt new maps when members failed to act.

Although reform efforts were also meant to reduce the number of cases that come before the ZBA, the body still handled dozens of cases a week, and applicants for variances almost always won them. According to a 2014 City Paper report, in one month eighty-five cases were considered and only ten denials were issued, while between 2008 and 2013 90 percent of 6,946 variance appeals were granted.

The new code also remained heavily contested after its adoption. Many members of City Council attempted, with some success, to increase parking requirements and reduce density incentives in response to constituent complaints about parking, traffic, and the need to preserve their neighborhoods in their current state—much the same concerns that animated their predecessors a hundred years earlier .

This messy reality mirrored the original intention of those who crafted zoning policy a century earlier. Although the players were different, zoning remained a tool used to prevent massive neighborhood change and to protect the interests of those who already lived, or owned, in a community. For those who wished to see zoning utilized as an instrument of rational good government, the state of the policy was immensely frustrating, for zoning, remained, as it had from its origins, a creature of municipal realpolitik.

Jake Blumgart is a reporter for WHYY’s PlanPhilly. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History