Main Line of Public Works

Essay

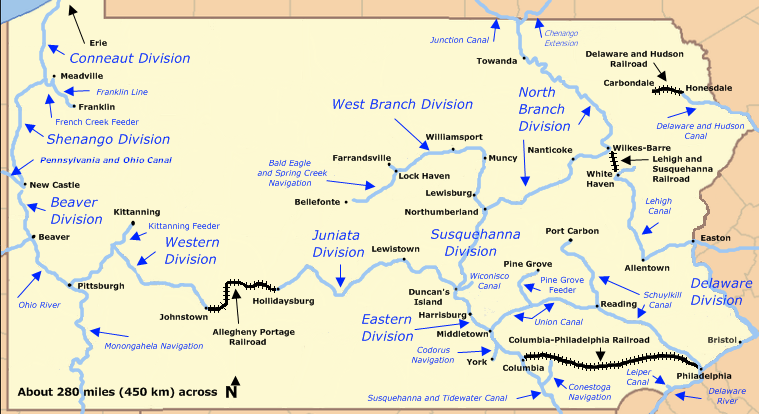

During the 1820s, seeking to compete with New York and Baltimore in tapping western markets, business and political leaders in Philadelphia pushed for a state-funded canal to link Philadelphia with Pittsburgh. The result, an innovative yet peculiar patchwork of canals and railways known as the Main Line of Public Works, succeeded in moving freight and passengers across the mountainous middle of Pennsylvania. The 395-mile system reduced travel time and spurred growth of towns and market activity along the line, but it proved costly to operate and plunged the state into debt. Within three decades, more powerful locomotives rendered the Main Line of Public Works obsolete.

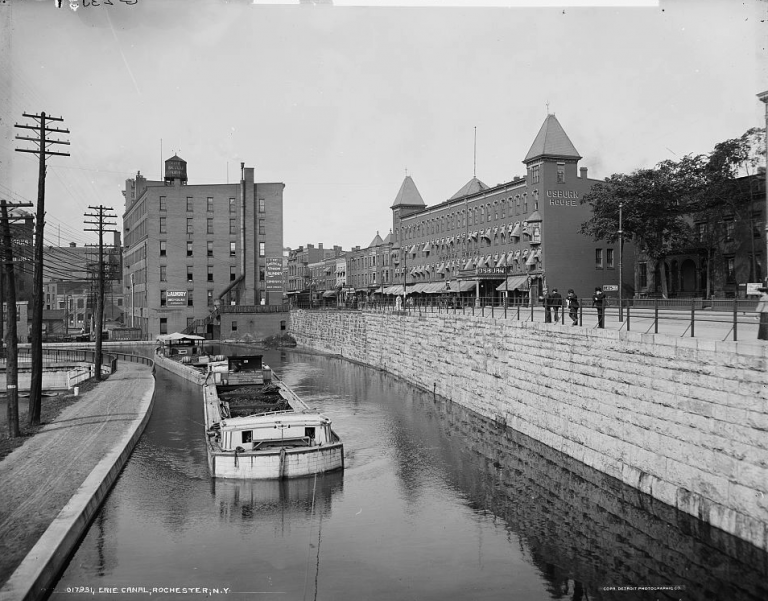

The impetus for the Pennsylvania canal scheme came largely from the looming threat of New York’s state-funded Erie Canal, which began construction in 1817. When completed in 1825, the canal linked the Hudson River to the Great Lakes, thus extending New York City’s orbit of trade to all the western interior and vastly increasing its competitive edge over Philadelphia. Additional threats to Philadelphia’s economic standing lay to the south, where Baltimore benefited from the movement of agricultural products down the Susquehanna River from Pennsylvania’s interior. The National Road, a federal east-west road project begun in 1811, also siphoned travel and trade from the southwestern corner of Pennsylvania into Maryland, where it connected with the Baltimore Turnpike.

Facing the loss of economic standing and recognizing the potential for trade as Americans moved west, Philadelphia business and political leaders campaigned for an improved transportation system to span across Pennsylvania. Since the colonial era, Philadelphia had looked west as far as Lancaster—about sixty-five miles away—for trade and travel enabled by the Philadelphia-Lancaster Road (a paved toll road after 1795). They also looked northwest to Reading, established in 1748 along the Schuylkill River. A canal between Reading and the Susquehanna Rivers, discussed since the 1790s, did not come to fruition until 1821. Meanwhile, developments in the early nineteenth century added to Philadelphians’ imagination of an economic region reaching farther into the interior of Pennsylvania and beyond: the state capital moved from Philadelphia to Lancaster in 1799 and then to Harrisburg in 1812; Pittsburgh grew from the site of a fort into a city; and new western states came into the union (Ohio in 1803, Indiana in 1816, and Illinois in 1818). Whetting appetites for new fortunes, opportunities in the West were growing as steamboats began to ply the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, reaching the expanding territory of cotton agriculture in the deep South. What could Philadelphians do to claim a share of the riches to come from the interior? How could they compete with New York and Baltimore, which seemed to be pulling ahead in the race to reach the West?

The Canal Campaign

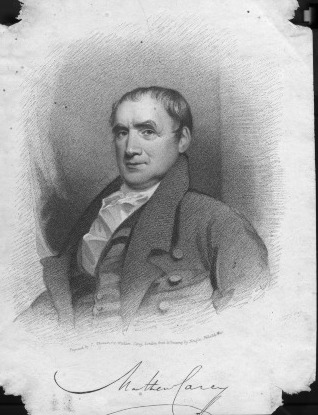

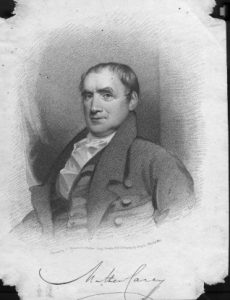

Matthew Carey (1760-1839), newspaper editor and political economist, launched a vigorous campaign for a state-funded canal between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. Together with such prominent citizens as Congressman John Sergeant (1779-1852) and Nicholas Biddle (1786-1844), then president of the Second Bank of the United States, Carey formed the Pennsylvania Society for Promotion of Internal Improvements. With dues collected from fifty-five members, the society dispatched the architect and engineer William Strickland (1788-1854) to England to study the latest in transportation technology. Although Strickland returned with data that included the newest technology, railroads, Carey pushed aggressively for the more time-tested alternative of canals. Petitions, pamphlets, newspaper editorials, and mass meetings added momentum, despite opposition from southern Pennsylvania counties that traded with Baltimore and northeastern counties with economic ties to New York. In 1825, an Internal Improvement Convention in Harrisburg endorsed Carey’s preference for a canal, and the next year the Pennsylvania legislature authorized construction of a state-funded Pennsylvania Canal between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. Adding a note of patriotic nationalism, construction began on the nation’s fiftieth birthday, July 4, 1826.

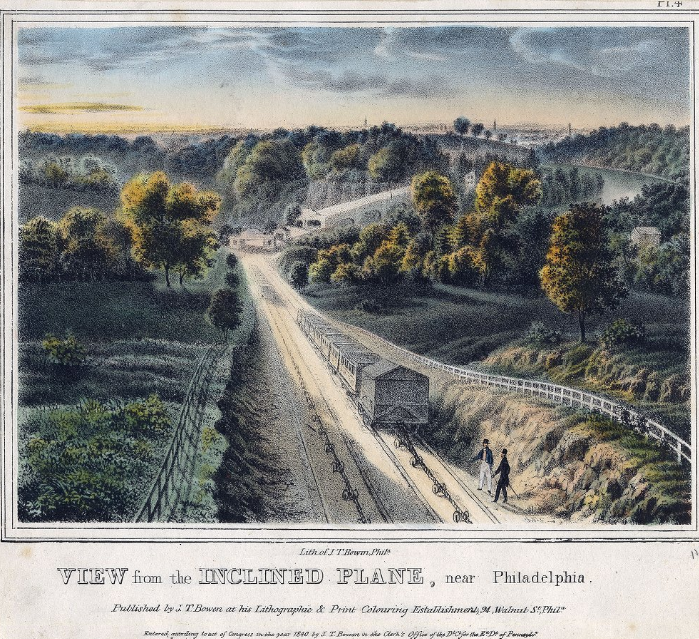

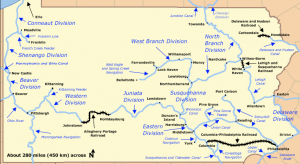

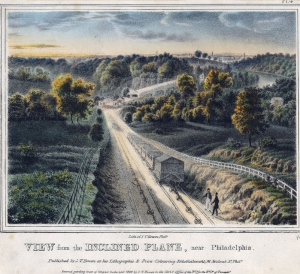

Canal fever faced unavoidable hurdles of geography. Across the breadth of Pennsylvania, the state’s major rivers offered good settings for canals, but not continuously and not in a straight line between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. And how could a canal possibly climb over the Allegheny Mountains? Such barriers did not stop the Main Line of Public Works. After nine years of construction, the system offered a journey that started in Philadelphia by rail—but the new Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad first moved by horsepower from a terminal near Broad and Vine Streets (then the northern city limits) across the Schuylkill via a newly built Columbia Viaduct Bridge. Then, a stationary steam engine pulled the cars by cable up an inclined plane to the top of Belmont Plateau in the area later incorporated into Fairmount Park. Thus positioned, cars could be joined to a steam locomotive to ride the rails west via Lancaster and down another inclined plane to Columbia on the Susquehanna River.

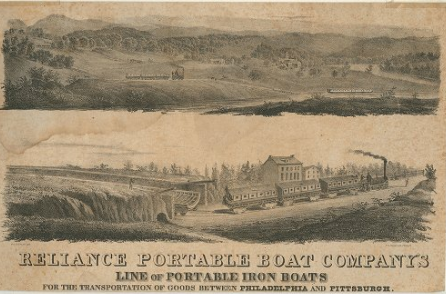

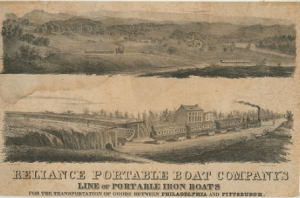

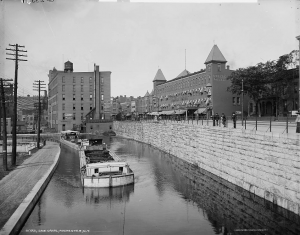

From Columbia, the journey continued northwest by canal alongside the Susquehanna and Juniata Rivers until the densely forested Allegheny Mountains blocked the way. At this juncture, at the town of Hollidaysburg, the trip required changing from water travel to another system of inclined planes, this one far more extensive than the beginning incline in Philadelphia. The Allegheny Portage Railroad involved hauling cars along a thirty-six-mile sequence of ten inclines and through a tunnel—the nation’s first for a railroad—to conquer a 1,400-foot change in elevation. After the trip over the mountains, the Main Line continued by canal from Johnstown to its ultimate destination in Pittsburgh. By the 1840s, the burdens of transferring people and cargo between canals and railways diminished with the introduction of canal boats that could be separated into sections to ride on rail cars when necessary and then reattached to return to the water.

Human Toll of the Route

Built at a cost of more than $12 million, the Main Line also extracted human costs as laborers, many of them Irish immigrants, constructed the system’s railroads, canals, 174 locks, forty-nine aqueducts, and three tunnels. At a spot in Chester County known as Duffy’s Cut, fifty-seven Irish laborers for a contractor building the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad died during a cholera outbreak during the summer of 1832. Later archaeological investigation revealed blunt-force trauma to some workers and one with a bullet wound.

The Main Line of Public Works succeeded to the extent that it cut travel time between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh from twenty-three days to about four, and it moved both freight and people between Philadelphia and the West. However, it did not restore Philadelphia to its earlier primacy in American trade because it could not compete successfully with the lower costs and easier transit available on the straight-line Erie Canal. Nevertheless, the Main Line brought products such as wheat, flour, whiskey, and lumber into the port of Philadelphia, and it carried manufactured goods from the city to the interior. Along the line, Columbia, Hollidaysburg, and Johnstown became bustling towns. The Main Line’s passengers included the English novelist Charles Dickens (1812-70), the “Swedish Nightingale” singer Jenny Lind (1820-87), and Jarena Lee (1783-64), the African American circuit preacher. The system also played a role in the Underground Railroad, as abolitionists including the lumber partners William Whipper (1804-76) and Stephen Smith (1795-1873) used their own boats and rail cars to move freedom seekers surreptitiously along the line.

By the 1850s, however, more powerful locomotives made railroads a more feasible option through mountainous terrain as well as a faster alternative to canals. In 1857 the state, deeply in debt from construction of the Main Line and other canals, sold the line to the Pennsylvania Railroad Company. Engineering of the Horseshoe Curve in central Pennsylvania ended the need for the Portage Railroad, which faded, abandoned, into the landscape. The “Main Line” ceased to exist in its original form, but the name nevertheless survived for the subsequent line of the Pennsylvania Railroad and especially in reference to the elite suburbs that developed along the line west of Philadelphia. Remnants of the system through central Pennsylvania became recreational trails and parks, and tourists could visit the Allegheny Portage Railroad National Historic Site managed by the National Park Service.

Although short-lived, the Main Line of Public Works helped to link the eastern seaboard to the expanding interior of the United States. At a time when national politicians debated whether the federal government should play a role in “internal improvements,” the Main Line tapped state funds for the system sought by boosters of Philadelphia. In the end, though, New York’s Erie Canal proved to be more effective—even some merchants in Philadelphia shipped goods to the West via New York rather than bear the cost of multiple transfers of the Main Line.

Charlene Mires is Professor of History at Rutgers-Camden and Editor-in-Chief of The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2020, Rutgers University