Food Processing

Essay

The food industry has always held a special place in Philadelphia and its surrounding region, though it never became a center of a massive industry like meatpacking in Chicago. Still, the methods of processing food at different periods and the people who did the work tell much about the state of Philadelphia’s economy and its residents. From colonial times, when most Americans processed their own foods, through the rapid changes in food manufacture introduced by the industrial revolution, to the consolidation and globalization of the food industry in the late twentieth century, the ways agricultural produce has been transformed into food and consumed at Philadelphians’ dinner tables has defined both the changing economic structure of the region and its level of integration within the larger world.

The indigenous and early colonial residents of the Delaware Valley were largely self-sufficient. The minimal processing needed to make bread or to preserve meat was done mostly at home or on the farm. Yet the inklings of the future food industry were visible in the trades marching in the Philadelphia Grand Federal Procession in 1788 celebrating the new Constitution: bakers, butchers, sugar refiners, and brewers joined their fellow predecessors of the coming Industrial Revolution in the line of march. And even in this early period, food processing brought the region into the global economy. Hogs driven to Philadelphia for slaughter and grain transported to the city for milling ended up not only in market stalls on High Street (later Market Street) but also as provisions traded for Caribbean sugar destined for the city’s refiners.

Philadelphia’s propitious location in the midst of the rich agricultural lands of southeastern Pennsylvania and southern New Jersey made it the natural location for the artisans and merchants who would establish a wide array of food-processing businesses. Yet until the mid-nineteenth century only flour milling, brewing, and sugar refining had established enterprises beyond the size of small artisanal shops. Philadelphia, in fact, became the center of the new country’s largest food industry, dominating flour milling in the late eighteenth century through the first third of the following century and exporting some 400,000 barrels of flour (and a smaller quantity of corn meal) per year. The city also housed many sugar refineries from the late eighteenth to the late twentieth century.

Although leadership in flour milling fell first to Baltimore and then the Midwest, Philadelphia, Camden, and nearby towns soon saw phenomenal growth in an amazing range of food-related industries: canning, the baking of bread, biscuits, and soft pretzels, candy-making, meat processing, the production of ice cream, mustard, and vinegar, and much more. Most new companies were of the type Philadelphia was best known for: small- to medium-sized and family-owned, often operating in the production of specialty items. But some of them grew to become national or world leaders in the mass production of food products and obtained financing from sources of capital beyond the wealth of their founding families.

Food Processing Outpaces Manufacturing

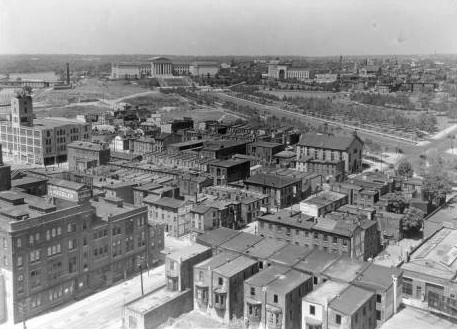

Spurred by the demands of war and growing urban populations, food industry expansion nationally outpaced manufacturing as a whole in the late nineteenth century, and, in Philadelphia, food processing become the city’s second largest industry (after textiles) by 1910. Canning, invented to feed Napoleon’s armies, became essential in the Civil War and remained so in America’s twentieth-century conflicts and in ordinary consumption.

Urbanization separated more and more people from the farms that produced their food, and the new advertising industry, as well as the promise of lightened housework, helped convince Philadelphia housewives (and others) that they needed factory-made canned soup and mass-produced sliced bread. Fears of contamination that led to governmental regulation also provided advertisers with arguments for why consumers should buy brand-name (and government-inspected) ice cream and cellophane-wrapped chocolates. Philadelphia’s many ethnic groups expanded the range of food processing methods and markets even further. Meat processing, for example, took the form of a first-floor Kosher butcher shop in West Philadelphia, an Italian basement butchery in South Philadelphia, and a Polish smokehouse in Port Richmond.

Canning, more than any other food-processing sector, brought the industrial revolution to the cities, towns, and hamlets of the Delaware Valley in the second half of the nineteenth century. In virtually every town in the lush agricultural region surrounding Philadelphia, tinsmiths built canneries, partnered with farmers and merchants, and sold their products not only in the city, but along the trade routes stretching west along the railways. When the steamboat Bertrand sank in the Missouri River in 1865, it carried to the bottom peaches and cranberry sauce from canneries in Philadelphia and southern New Jersey (as well as rival Baltimore). Canning also spurred development of allied industries. Southern New Jersey’s glass manufacturers provided the first containers for the industry, and several can makers followed (like the Continental Can Company located next door to Campbell Soup in Camden), while Bridgeton’s Ferracute Machine Company built canning machinery used throughout the region. This growth of related industries and synergies among producers of raw materials, intermediate outputs, and final consumer goods was seen most clearly in the case of canning, but it was a phenomenon that characterized all branches of the food industry in the Delaware Valley.

Most canneries remained fairly small, but several grew into sizable establishments, employing hundreds or even thousands of workers, typically doubling in size during harvest season. Philip J. Ritter first tried his hand at confectionery, but had more success when he began selling his wife’s preserves in 1854. When operations outgrew the family’s Kensington home twenty years later, he opened a factory on Dauphin Street. By 1894 his cannery employed 150 workers year-round and 300 at peak season. To get even closer to its raw materials, especially tomatoes for its award-winning Ritter Catsup, the company opened a plant across the river in Bridgeton, New Jersey. An even more famous product, Campbell’s Soup, rolled off the lines of that company’s mammoth plant in Camden.

New Eating Habits

Eating new items like canned soup was something Philadelphians were learning to do, but bread and other baked goods had been part of their diet from colonial days. Yet even with the onset of the industrial revolution, most people in the city and surrounding towns continued baking bread at home or purchasing it from the hundreds of small neighborhood bakeries. The first attempt at building a large mechanized bread bakery at Broad and Vine Streets in 1857 ended in failure three years later. But by the end of the nineteenth century a number of local bakeries and branches of national bread makers had implemented modern production and distribution methods, and brands like Freihofer‘s and Stroehmann’s became household names.

One of the main obstacles to commercial production of bread was overcome by Charles Fleishmann’s (1835-1897) invention of consistent packaged yeast in 1868 in Cincinnati. His “Vienna Model Bakery” became one of the highlights of the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in 1876. The Model Bakery moved to 253 North Broad Street after the Exposition (managed by Fleischmann’s brother-in-law) and the company expanded from there to Manhattan and elsewhere. Other bakers quickly adopted the use of commercial yeast, and store-bought brand-name bread spread rapidly. Philadelphia baker Charles Freihofer (1860-1942) continued the Vienna theme when he teamed with his brother to open the Freihofer Vienna Baking Company in Camden in 1899 and a similarly named company at 24th and Master Streets in North Philadelphia a year later. Rapid growth in the business led to a move to 20th and Indiana Streets in 1913 and expansion to several other cities. Freihofer’s and competitors’ home-delivery vans, originally horse-drawn, became a fixture in Philadelphia’s neighborhoods as many smaller bakeries closed their doors.

Entrepreneurs Philip Bauer and Herbert Morris conceived the idea of mass-producing and marketing small “sanitary-wrapped” cakes and opened a plant on Sedgley Avenue in 1914. Their Tasty Baking Company was so successful that “Tasty Kakes” became a Philadelphia icon. By 1922 they moved to a much larger facility on Hunting Park Avenue. Other Philadelphia traditions remained the province of smaller establishments. Small soft pretzel bakeries were found in almost every neighborhood, though some, such as Federal Pretzel Baking Company in South Philadelphia, introduced limited mass-production techniques to increase their output. Similarly, the rolls used for Philadelphia’s cheesesteak sandwiches and hoagies came from a variety of bakers. But the Amoroso family enterprise, originally just another small bakery in Camden in 1904, repeatedly outgrew its facilities until it was able to produce enough rolls to meet region-wide demand in a large plant on South 55th Street in Southwest Philadelphia.

Although large-scale production of breads and cakes got off to a slow start in Philadelphia, the manufacture of biscuits and crackers was well established by the Civil War, when “hard-tack,” a hard, usually saltless biscuit, was widely used for military rations. Godfrey Keebler (1822-93) had worked in a number of bakeries by the onset of the war, and in 1862 opened a bakery in South Philadelphia. His success from supplying the Union Army as well as the Philadelphia market led to expansion to a mechanized facility at 258-264 N. Twenty-Second Street and later, after a merger that formed the Keebler-Weyl Baking Company, to a large plant at G Street and East Hunting Park Avenue. The National Biscuit Company conglomerate (formed in 1898) also opened operations in Philadelphia at Broad Street and Glenwood Avenue, and later near the Roosevelt Boulevard in the Far Northeast section of the city.

Confectionary Leader

Philadelphia has also long been a leader in the confectionery industry. Stephen F. Whitman (1823-88) opened a confectionery shop on the waterfront in 1842 and introduced prepackaged candy in 1854. His company pioneered the use of cellophane in its famous Whitman’s Sampler (1912) and moved several times, eventually to Fourth and Race Streets. It relocated once again, in 1960, to a new industrial park in the Far Northeast, where it employed 1,650 workers. (Another Philadelphia candy shop, opened in 1873 by the young Milton Hershey [1857-1945], failed after a few years; he moved about a hundred miles west where he founded the Hershey Chocolate Company in 1894.) Among other well-known Philadelphia candy makers were Richardson’s Mints (1893), C. A. Asher (1892, moved to Germantown in 1899), and David Goldenberg (who started his candy store on Kensington Avenue in 1890 and created Goldenberg’s Peanut Chews as a World War I ration in 1917).

A related industry, the manufacture of ice cream, was also important in Philadelphia. Among other ice-cream makers in the city, William A. Breyer (1828-82) began making ice cream in 1866 and opened a retail store on Frankford Avenue in 1882. The business was continued by his wife and sons after his death. The company trumpeted the pure ingredients of its ice cream, and growing sales led to several moves, eventually to a large plant at Forty-Third Street and Woodland Avenue that employed 500 workers by 1931.

Meat, poultry, and seafood processing have been small but continual parts of Philadelphia’s food industry from the beginning from the beginning. Excellent transportation to the West enabled meat processors to supply the needs of the large regional market. A few small-to-medium-sized slaughterhouses were found in the area, such as Cross Brothers in Kensington and Triolo’s in Burlington County, New Jersey. Dietz and Watson started making delicatessen meats in 1939 and expanded to other cities while maintaining a large plant in the Tacony section of the city. The nineteenth-century shad fisheries and markets of Shackamaxon even resulted in the change of that neighborhood’s name to Fishtown.

Local Consumers Were Producers, Too

Philadelphians were not only consumers of the products of the companies founded by the area’s food industry entrepreneurs; residents of working-class neighborhoods throughout the region were also the ones who did the work that turned agricultural raw or semi-processed materials into finished products. And that work was often long, hard, and low-paying, especially before employees joined together in unions to press for better pay and working conditions. Among the first recorded activities of united Philadelphia food workers was a strike for higher wages by the Journeymen Bakers in 1835. Journeymen Biscuit Makers were mentioned in the press a year later. Some crafts in the industry were unionized over the next century, but it was only after the organizing drives of the Congress of Industrial Organizations in the 1930s that most of the areas food workers became union members–even the 1,500 confectionary workers who organized Candy Workers Local 350. Union contracts improved the lives of food workers but often only after strikes and other industrial actions. One example among many was the strike of 1,900 bakers in 1946 against eight major bakery firms including Freihofer and Fleischmann in Philadelphia and Stroehmann Brothers in Norristown. Working-class support for unions and picket lines was impressive. A sense of the strong traditions against crossing picket lines can be garnered from an arbitrator’s report about what happened at Cross Brothers Meat Packing Company when employees who had struck a different unit of the company crossed the street to an unrelated division of the firm:

On July 1, 1971, [Cross Brothers] expected approximately 65 slaughterhouse and 18 boning employees to report for work. None reported, since they refused to cross the Local 195 picket line. The office and clerical employees and the delivery employees, represented by Teamsters’ locals 161 and 500 respectively, similarly did not report for work. . . . Employees of an independent contractor building an addition to Packers’ building, as well as those of a garbage removal contractor, also refused to cross the picket line in order to perform their job duties.

Several of the most intense clashes between workers and management in the food-processing industry occurred in South Jersey, especially at Campbell Soup in Camden and Seabrook Farms in Cumberland County. The workers at Seabrook, mostly African Americans and Italian immigrants, who were paid 12-15 cents per hour, initially won a big increase in their wages when they struck in 1934, but their union was destroyed a few months later after concerted attacks by company, police, and vigilantes.

By the early twenty-first century much of Philadelphia’s food processing industry had disappeared or been absorbed into global food mega-corporations, though, just as in earlier centuries, small establishments continued to compete in various niches. There were many reasons for the decline. The rich agricultural hinterlands of the city that had supplied canneries and other food processors were no longer the source of raw materials. Although local farms still produced a smaller amount of food for the fresh market, food processors preferred cheaper mass-produced intermediate inputs like tomato paste from California and China. Beyond reasons specific to the food industry, Philadelphia’s food workers suffered along with others from the increasingly aggressive cost-cutting strategies of global capitalism that ramped up in the 1970s. The lure of highly automated factories with fewer workers, remaining workers who would accept lower pay and not join unions, states and countries offering corporate tax breaks and little regulation, and repeated bouts of merger-and-acquisition mania all took their toll on Philadelphia’s industries, including its food processors.

Recent Consolidation

Freihofer’s and Stroehmann’s breads (along with Arnold’s, Entenmann’s, and others) had been absorbed into the largest bakery corporation in the United States, Bimbo Bakeries, a unit of Mexico’s Grupo Bimbo. Area residents might have taken some comfort from the fact that Bimbo’s American headquarters located in Horsham in Montgomery County. Tasty Baking Company closed its Nicetown plant and moved to a new taxpayer-subsidized facility at the former Navy Yard in 2010. Because the new plant was highly automated, hundreds of employees were laid off. Yet the company avoided bankruptcy only by becoming part of Georgia-based Flowers Foods (a Bimbo competitor). After Whitman’s Chocolates’ much-heralded move to the new Philadelphia Industrial Park in 1960, it was sold to Pet, Inc. When Pet later sold the brand to Russell Stover Candies in 1993, it closed the Philadelphia plant. Breyer’s Ice Cream went through several corporate owners; it became part of the Anglo-Dutch multinational Unilever in 1993 where it made mostly “frozen dairy desserts” rather than ice cream. It laid off the 240 workers at its Philadelphia plant in the mid-1990s and demolished the building. One of the city’s oldest industries–sugar refining–ended with the closing of the National Sugar refinery (Jack Frost sugar) in Fishtown in 1981 and the Amstar (formerly Franklin) refinery (Domino sugar) in South Philadelphia a year later.

Still, food processing companies large and small remained in the area in the twenty-first century. Cross Brothers was gone, but 400 workers at Dietz and Watson continued curing meat in Tacony, and the Czerw family still smoked kielbasa in its Port Richmond smokehouse. Keebler’s factory in Juniata was closed long ago (and the company itself had been absorbed into Kellogg’s), but 700 workers still made cookies and crackers at the Nabisco plant in Northeast Philadelphia, though it had changed ownership by then to Kraft Foods. Federal Soft Pretzel Bakery was sold to snack food giant J&J Snack Foods Corporation across the river in Pennsauken in 2000, but Philadelphia Soft Pretzels continued hand-twisting pretzels at its Feltonville bakery, though by then it was competing with dozens of new franchised pretzel makers.

The Philadelphia food-processing industry had fallen far from its important position of the early twentieth century. Most large mass-production facilities had taken the same route as the region’s other large manufacturers and moved to newer and cheaper locations in the globalized food economy. Some foods that had short shelf life or were difficult to transport were still made in plants in or near large cities, including Philadelphia. For example, while Bimbo managed all of its U.S. holdings from Horsham, it still relied on local bakeries (such as Stroehmann’s) for most of its bread production (and it continued using old local brand names). A few independent companies with strong local ties (like Dietz and Watson) still employed hundreds in the area, and the growing ranks of “foodies” and newer immigrant groups provided opportunities for numerous niche producers of specialty and ethnic foods. These, along with a handful of national and global corporate headquarters of food companies like Campbell and Bimbo, marked the latest stage in the history of food processing in Philadelphia.

Daniel Sidorick has taught history at Temple and Rutgers Universities and the College of New Jersey. His book Condensed Capitalism: Campbell Soup and the Pursuit of Cheap Production in the Twentieth Century (Cornell University Press) was awarded the Richard P. McCormick Prize by the New Jersey Historical Commission. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History