Roman Catholic Education

(Elementary and Secondary)

Essay

Parochial schools in the Philadelphia region share a common Catholic mission and similar patterns of growth and development. For more than three centuries they have responded to the changing characteristics of the region’s Catholic population. Several of these developments, such as schools for specific ethnic groups, occurred in Philadelphia, Camden, N.J., and Wilmington, Del., within years of each other. However, the Roman Catholic Church served a larger, more diverse, and faster growing population in Philadelphia than in Camden or Wilmington, and consequently Philadelphia’s parochial schools became more organized.

The Philadelphia parochial school system began in 1852 under the leadership of John Nepomucene Neumann (1811-60), the fourth bishop of Philadelphia. The roots of Catholic education, however, extend back to the colonial period and throughout the Mid-Atlantic region. The earliest recorded Catholic school in the region, and arguably the oldest Catholic school in the English-speaking colonies, was St. Mary’s, founded by the Jesuits about 1640 in Newtown, now in the state of Maryland. By 1743 a Jesuit also opened one of the first Catholic schools in Pennsylvania, St. Aloysius Academy, in Berks County. This one-room school focused on reading, writing, and spelling, and was open to both Catholic and non-Catholic children.

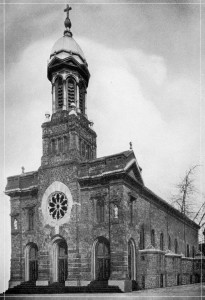

Perhaps the first Catholic school in Philadelphia appeared in 1692. The first Catholic “school mistress” may have been Ann Bryald, who opened a school sometime before 1771 for Acadian children who came in 1756. It is certain, however, that St. Mary’s parish school, for which a new building was constructed in 1782, was among the first, if not the first, full-fledged Catholic school in Philadelphia. It had a paid faculty, a specified curriculum, and methods of pupil assessment. Funding came from charity sermons, bequests from parishioners, and, for a time, investment income from shares in the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike. By 1805, the school offered evening classes for older children and adults. Philadelphia also gained an ethnic Catholic school in 1787, when the German Catholic Society opened a school (near Sixth and Spruce Streets) run jointly with the German parish of the Holy Trinity.

From the late eighteenth through the nineteenth century, the governance of the Catholic Church reshaped the region for parochial education. The Diocese of Baltimore, the first in the nation (1789), was divided in 1808 to create the Diocese of Philadelphia that served the needs of Catholics in Pennsylvania, Delaware, and western and southern New Jersey. A further realignment in 1853 made Camden part of the newly-formed Diocese of Newark, New Jersey.

The Early Schools

By the first decades of the nineteenth century, Catholic schools operated in each of the region’s major cities. In the 1840s, Philadelphia children attended Catholic schools at St. Mary’s (104 S. Fifth Street), St. Patrick’s in the “Village” (the area around Rittenhouse Square), St. Joseph’s (near 321 Willings Alley), St. Augustine’s (Fourth and New Streets), possibly at St. John’s (Thirteenth Street below Market Street), and at St. Joseph’s Orphan Asylum (near Seventh and Spruce Streets), which previously taught children orphaned by the 1793 yellow fever epidemic. Sunday Schools, which taught religion as well as secular subjects, appeared in many parishes. Open to all age groups and taught largely by lay volunteers, many of these schools met just for two hours a week.

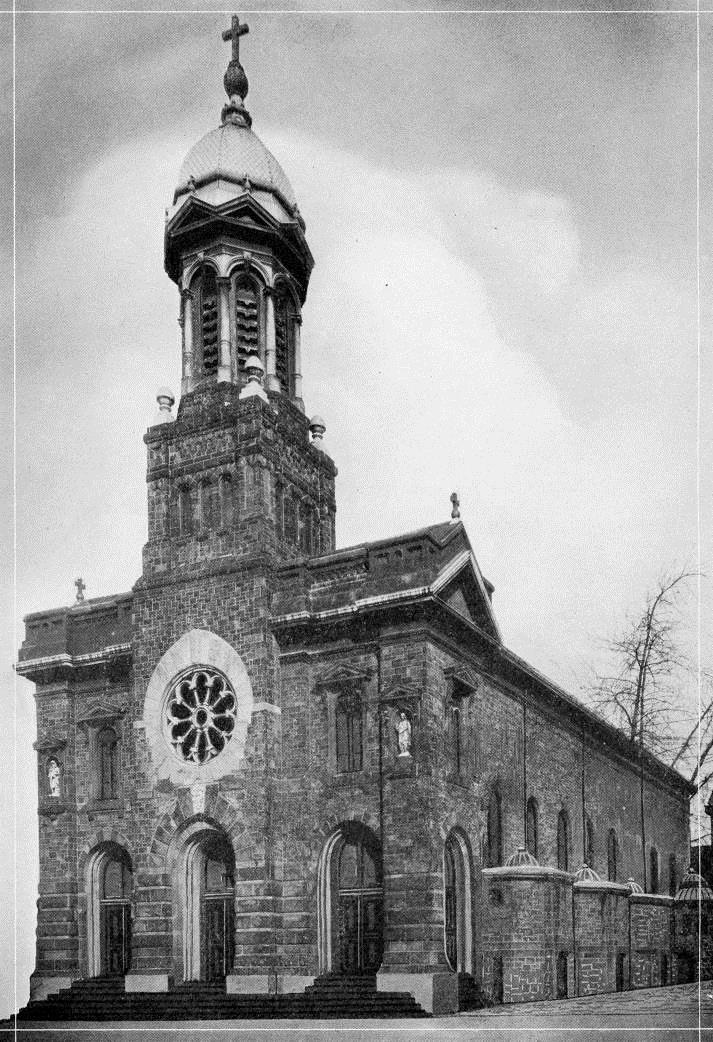

In Wilmington, St. Peter Cathedral School (at 310 W. Sixth Street) opened in 1830 to educate the orphans of workers killed in accidents at the DuPont gunpowder works. The children were taught by three Sisters of Charity from Elizabeth Ann Seton’s religious community in Emmitsburg, Maryland. The school became a boarding school and eventually a diocesan elementary school.

The first parochial school in Camden, St. Mary’s, opened in 1859 when Sarah Fields held classes in her home at Fifth and Arch Streets. In 1862, the school relocated to the second floor of a newly completed church (at Fifth Street and Taylor Avenue). The same year, another St. Mary’s, this one in Gloucester City, also opened a school in the parish rectory (near Cumberland and Sussex Streets) with twenty students who were taught by a lay teacher, a seminarian, and a priest. Although not part of a system, parish schools in New Jersey continued to grow, and after 1865 every church with a resident priest operated a parochial school.

Parochial education expanded as the region’s increasing population of Irish Catholics encountered hostility from native-born Americans. In 1836 the Pennsylvania legislature gave the Philadelphia Board of Education a monopoly of public education money, and its pauper schools, dating from 1818, were opened to all children. Many Catholic parents enrolled their children in these common schools, but it was not long before Catholic leaders began to have doubts about them. For instance, they used the King James Bible, the “Protestant” version. In 1842 a Catholic teacher was dismissed for refusing to read from it. When Peter Parlay’s Common School History was adopted, the Catholic press complained about its anti-Catholic passages. In protest, Bishop Francis Kenrick (1796-1863) asked that Catholic children attending Philadelphia public schools be granted the freedom to read from the Catholic version of the Bible.

By 1854, 34 Parochial Schools

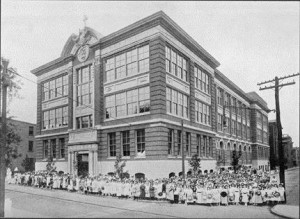

After Philadelphia’s nativist riots of 1844, Kenrick, appalled by the destruction and bloodshed, gave up trying to make the public schools suitable for Catholic children and pushed for parochial schools instead. By 1850, nearly every parish in Philadelphia had a free school, and by 1854, the diocese had thirty-four parochial schools with an enrollment of almost 9,000. Under Bishop John Nepomucene Neumann, the schools became a Philadelphia parochial school system administered by a central school board. Its duties included making plans for funding school construction and recommending policies for hiring teachers, whose salaries were to be paid by each parish..

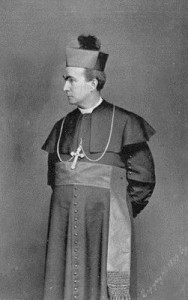

In 1875, the Diocese of Philadelphia became an archdiocese and Bishop James Frederick Wood (1813-1883), Neumann’s successor since 1860, became its first archbishop. Downsized from its previous boundaries, the archdiocese now covered Philadelphia, Berks, Bucks, Carbon, Chester, Delaware, Lehigh, Montgomery, Northampton, and Schuylkill counties. In 1894 Wood’s successor, Archbishop Patrick John Ryan (1831-1911), appointed the first superintendent of Catholic schools in the archdiocese, Father John W. Shanahan (1846-1916). He was followed in 1899 by Father Philip McDevitt (1858-1935) who systemized the supervision of each school. By expanding the School Board and refining school administration, Ryan established the system that exists today..

The curriculum in the Philadelphia parochial schools at the close of the nineteenth century was, except for religion classes, prayers and liturgies, almost indistinguishable from that of the Philadelphia public schools. Pastors and school board members worried about maintaining the faith of the students, but they also wanted a curriculum that was as structured and rigorous as that found in the city’s public schools, thereby assuring Catholic parents that they would not be short changing their children if they sent them to a parochial school.

The influx of Catholic immigrants from southern and eastern Europe at the end of the nineteenth century led to conflict among Roman Catholics because the new arrivals and even some of the Germans, who were by then well-established, felt disrespected by the “Hibernians” (Irish) whose churches, schools, and bishops now dominated the archdiocese. To accommodate the needs of these recent Catholic immigrants, ethnic parishes and bilingual schools were established throughout the region. These schools tempered the trauma of immigration because their teachers, many of whom were members of religious communities from Poland and Italy, spoke the language and knew the culture. Some of these nuns, however, spoke English so poorly that they were not effective models for Americanization.

Italian Parish Schools

In Philadelphia, the Italian parish schools that opened during this period included Our Lady of Good Counsel (1898, near Eighth and Christian Streets), St. Rita (1907, near Broad and Ellsworth Streets), and St. Donato (1910, at 405 N. Sixty-Fifth Street). St. Mary Magdalene De Pazzi, the oldest Italian parish in the United States, founded thirty years earlier, also began a school in 1874 with teachers from the Missionary Sisters of St. Francis. Schools for German-speaking Catholics opened in Port Richmond, a river ward on the Delaware River, at Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary parish (Belgrade Street and Allegheny Avenue) and later Our Lady Help of Christians (Allegheny Avenue and Gaul Street). Eighteen Polish parishes opened throughout the archdiocese, including six in Philadelphia. In 1904, St. Adalbert (Thompson Street and Allegheny Avenue) was founded just one block east of Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary. The Sisters of the Holy Family of Nazareth, a Polish order, taught there.

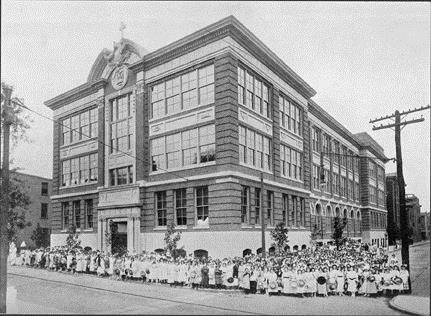

The pattern was similar in Camden, which in 1881 became part of the newly-created Diocese of Trenton. Adding to Saints Peter and Paul, a church and school for German-speaking Catholics established in 1868-1869 at Fourth and Division Streets, Bishop Michael O’Farrell (1832-94) authorized building St. Joseph Church (Tenth and Liberty Streets) for Polish-speaking Catholics in 1882. Initially run by lay teachers, its school was later taken over by the Sisters of Nazareth and then by the Felician Sisters. A new three-story school with sixteen classrooms was opened in 1914. For Italian speakers, Our Lady of Mt. Carmel parish was founded in 1903 on the site of the former Church of Saints Peter and Paul, which had relocated to Spruce Street above Broadway. Our Lady of Mt. Carmel parish school appeared in 1908. Referred to as St. Michael’s School until the 1920s, it initially enrolled 319 children and was staffed by two nuns and a laywoman.

Wilmington gained a school for German-speaking Catholics in 1878 (at Sacred Heart, 917 North Madison Street) and for Poles in 1897 (at St. Hedwig, 408 Harrison Street). In 1924, St. Hedwig constructed a new school building to accommodate 925 children, making it one of the largest parochial schools in the city. St. Stanislaus Kostka parish (901 East Seventh Street) was founded in 1912 in east Wilmington, near the shipbuilding and leather tanneries on the Delaware River, so that Polish parents and their children would not have to travel across town for church services. Three Felician sisters opened an elementary school there in 1914. The first parish for Italian Catholics in Wilmington, St. Anthony of Padua, was established in 1924 and opened a school in 1938 under the direction of the Franciscan Sisters from Glen Riddle, Pennsylvania.

Ursaline of Wilmington

Catholic secondary education in the nineteenth century occurred primarily in tuition-based private academies or pre-collegiate independent schools. They developed “collegiate departments” that ultimately led to the founding of some local Catholic colleges (for example La Salle University and Chestnut Hill College). In 1890, the Philadelphia archdiocese opened Roman Catholic High School, the first free Catholic secondary school in the United States. Father Nevin F. Fisher, the first rector, supervised a faculty comprised exclusively of laymen. In 1912, the archdiocese opened Catholic Girls High School at 311 N. Nineteenth Street. With the opening of these two high schools, the archdiocese now provided education from the first through the twelfth grades, mirroring closely the structure of the Philadelphia public schools.

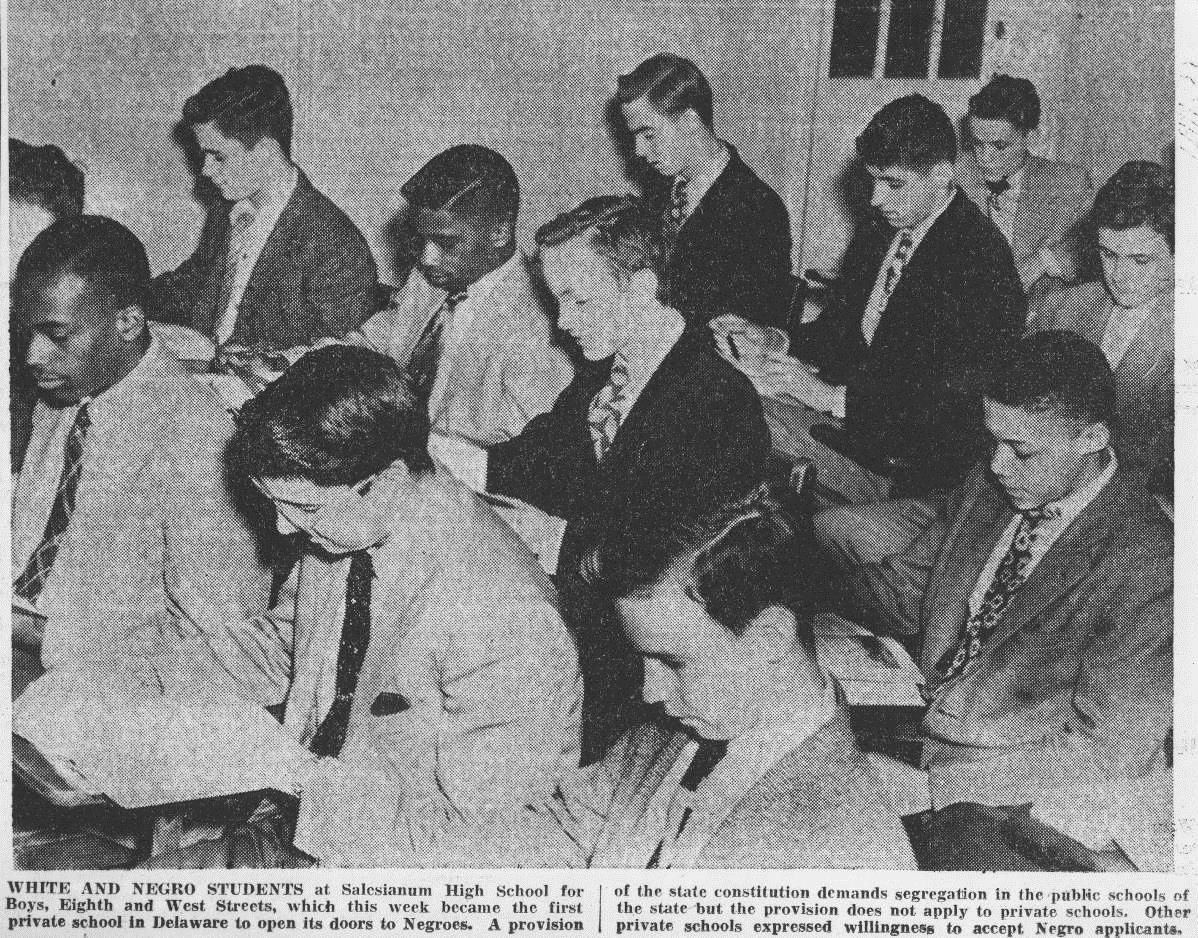

Catholic secondary education existed in both adjacent dioceses by the 1920s. Wilmington’s Ursuline Academy, the only all-female Catholic high school in Delaware until 1930, opened in 1893, followed by Salesianum School in 1903, the first all-male independent Catholic high school in the state. The oldest Catholic high school in South Jersey, Camden Catholic High School, opened in 1924 (originally at Seventh and Federal Streets) as a four-year, co-educational institution with 400 students and a four-track curriculum.

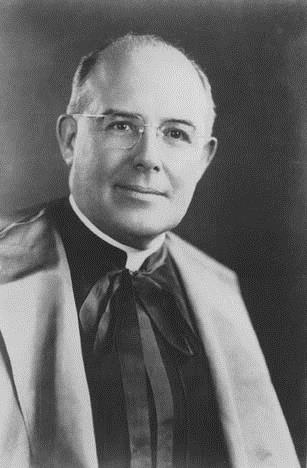

The first half of the twentieth century witnessed dramatic changes in the curriculum of the Philadelphia parochial school system and the preparation of its teachers. By 1930 more than 4,000 nuns were certified in elementary education, in part because the Pennsylvania legislature had waived the requirement that student teaching be done in a public school. To provide needed training, demonstration schools and Schools of Practice were opened so that novice teachers could learn from veterans. Education professors from Villanova University taught methods classes at Hallahan Catholic Girls High School, one of the first demonstration schools. Teachers also took summer courses at Catholic and secular universities, and annual teacher institutes became more professional in focus, with regional and national authorities invited to speak. Under the leadership of Monsignor John Bonner (1890-1945), the superintendent of Philadelphia’s Catholic schools from 1926 to 1945, supervisors visited all classrooms to monitor instruction and classroom management. He also introduced standardized mid-year and final examinations, and grouped students according to cognitive ability.

The parochial schools in Camden and Wilmington did not have a fully developed administrative hierarchy until the middle of the twentieth century. Following the 1937 creation of the Diocese of Camden, encompassing Atlantic, Camden, Cape May, Cumberland, Gloucester, and Salem counties, Bishop Bartholomew J. Eustace (1887-56) established four high schools and twenty-two elementary schools and expanded many others. In 1941, he appointed the first school superintendent, Father William Hickey, who was followed ten years later by Monsignor Charles McGarry. Wilmington parochial schools, meanwhile, were led by part-time superintendents from 1932 until the appointment of Father Edmund Julien in 1957.

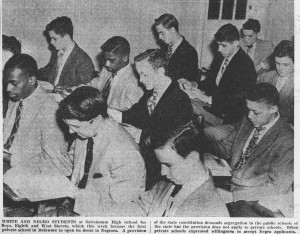

Philadelphia led the way in reforming Catholic secondary education in the region. No longer perceived to be a luxury, a high school diploma became common by the 1950s. The high school curriculum now prepared students for employment as well as college. Besides traditional subjects, many Catholic high schools in Philadelphia expanded their practical and vocational arts curricula to include mechanical drawing, elementary typesetting and printing, and auto mechanics. They offered extra-curricular and co-curricular activities, including music, debating, and both intramural and varsity sports. Many of these extra-curricular activities also appeared in the high schools of Camden and Wilmington. System-wide reforms in Philadelphia after World War II included basic science in the elementary schools and laboratory science in the high schools. In 1966, the archdiocese introduced a human relations program to foster appreciation for racial justice and to address challenges posed by diversity.

Meeting the “Baby Boom”

The “baby boom” that transformed the United States in the 1950s and 1960s had profound effects on the organization and geography of the region’s Catholic education. With the increase of population, Catholic leaders carved Berks, Carbon, Lehigh, Northampton, and Schuylkill counties from the Archdiocese of Philadelphia to create the Diocese of Allentown in 1961. The new diocese acquired 28,450 students, 109 elementary schools, and 13 secondary schools from Philadelphia, but because the archdiocese still included Philadelphia, Bucks, Montgomery, Chester, and Delaware counties, its schools were well attended. In 1964 there were 212,267 students in 286 elementary schools (102 fewer schools and 16,322 fewer students than in 1960), and 57, 237 students in twenty-five high schools (thirteen fewer schools but 1,511 more students than in 1960). Consequently, the archdiocese embarked on a building program that, by 1967, resulted in twenty-one new elementary schools and five new high schools, which brought the total by 1970 to thirty. Most of these new schools were in the fast-growing suburbs.

The Camden and the Wilmington dioceses also mobilized to accommodate more students, improve instruction, and refine administration. Between 1950 and 1965 the Diocese of Camden experienced the largest growth in its history, much of it driven by suburbanization. Its bishop, Celestine Damiano (1911-67), announced a drive in 1960 to raise $5 million to build and improve diocesan high schools that resulted in a new Camden Catholic (in suburban Cherry Hill in 1962), Cathedral Academy (on the site of the old Camden Catholic in 1965), and Pope Paul VI (in Haddonfield in 1966). He also authorized Superintendent Monsignor Charles McGarry to upgrade the secondary curriculum and guidance services, initiatives that were continued by Fr. John J. Clark when he became the superintendent after McGarry’s death in 1965. Damiano also created a diocesan board of education that included seven lay members. By 1965 the diocese had seventy-four elementary schools, thirteen high schools, 338 lay teachers, and 43,465 students.

Enrollment increases in the Diocese of Wilmington between 1950 and 1970 also led to the construction of several elementary and secondary schools, both diocesan and independent. The new Salesianum High School (at Eighteenth and Broom Streets) opened in 1957 at a cost of $3 million. It featured a 1,500 seat auditorium, a gymnasium, cafeteria, library, machine shops, a chapel, and a faculty house for priests who taught there. By 1968 the Diocese of Wilmington (encompassing the state of Delaware and the Eastern Shore of Maryland) had seven kindergartens, thirty-two elementary schools, four independent elementary schools, seven parochial high schools, and four independent high schools, serving 16,094 students.

High School Tuition

Expansion came at a cost. Philadelphia diocesan high schools charged tuition for the first time in the 1970s, followed later in the decade by the elementary schools. The number of lay faculty and lay administrators gradually increased, adding to the cost of operations. The archdiocese responded to continuing suburban growth by constructing two high schools, Bishop Shanahan in Downingtown, Chester County (1998) and Pope John Paul II in Pottstown, Montgomery County (2010). Meanwhile, the Catholic population in Philadelphia decreased, and the Pennsylvania Charter School Law, adopted in 1997, gave Catholic parents another option. The archdiocese addressed these issues by allowing open enrollment in its secondary schools, thereby permitting students to cross traditional boundaries. Parochial schools also accepted more non-Catholic children. The archdiocese lobbied in Harrisburg for educational choice legislation, an effort that was largely unsuccessful. But in 2012, Pennsylvania’s Educational Improvement Tax Credit Program was expanded to provide an incentive for businesses to contribute to scholarships for low-income students wanting to attend private, parochial, or higher-performing public schools.

Gradually, the Philadelphia archdiocese closed many schools and consolidated others. By 2012, its parochial school enrollment had decreased to about 70,000 students. In August of the same year, the archdiocese announced a five-year contract with the Faith in the Future Foundation, an independent agency that would manage the finances and enrollment of the diocesan secondary schools.

Similar circumstances faced the Camden and Wilmington dioceses. Overall enrollment in all Catholic schools in the Camden Diocese dropped from 28,796 in 1980 to 12,929 in 2012. By then, the cost of educating a single elementary student exceeded the tuition, which became a challenge because each school was responsible for its own finances. This led to school closures and mergers. To address this financial crisis, attorney and businessman Robert T. Healey founded the Catholic School Development Program (CSDP) in 2004 to help Catholic elementary schools with governance, enrollment, management, and development issues. By 2013, CSDP was working with five schools in Camden city and fifteen other schools in the diocese. Total parochial enrollment in the State of Delaware decreased from 13,513 in 2000 to 11,350 in 2009. Like the schools in the Camden diocese, those in Wilmington are responsible for their own finances. While the parochial schools in all three dioceses struggled with the financial aftermath of the 2008-9 recession, the Diocese of Wilmington experienced the added burden of declaring bankruptcy in 2011 because of a $77.4 million settlement paid to victims of sexual abuse.

The Catholic schools in the tri-state area ultimately compete with public education. Consequently, they stay current in national trends in curriculum, instruction, and administration. In 2012 the Philadelphia archdiocese split the superintendent’s office into two separate positions, one for elementary and the other for secondary education. In 2013, it also announced a new Executive Board of Elementary Education to assist elementary and regional schools with planning, enrollment, and governance. Schools in all three dioceses provide in-service programs for teachers based on research-based pedagogy and technology and are moving to adopt the Common Core State Standards. While Neumann and Ryan would not be familiar with the complex administration or the high-tech classrooms of the twenty-first century, they would recognize the faith-based mission that still animates Catholic education.

Francis J. Ryan is Professor and Director of American Studies at La Salle University. He is a co-author of Drowning in the Clear Pool: Cultural Narcissism, Technology & Character Education (Peter Lang Publishing, 2002). He is currently working on the history of progressive education in the Philadelphia Catholic schools, 1890-2010. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University