Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University

Essay

A group of six amateur scientists with an interest in natural history gathered at a private residence at High and Second Streets in Philadelphia on January 25, 1812, and founded the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia for, according to its charter, “the encouragement and cultivation of the Sciences” and “the advancement of useful learning.” These enthusiastic, mostly young men, soon joined by entomologist and conchologist Thomas Say (1787–1834), created what has become the oldest institution of natural history in America. The academy continued to produce important original research in biological and molecular systematics, ecology, and biodiversity as it forged important partnerships in the region and the world and eventually affiliated with Drexel University.

In the early nineteenth century, Philadelphia was already home to the American Philosophical Society, the Philadelphia Museum established by Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827), and a thriving medical community. But the academy founders, members of the city’s growing professional class, felt excluded and poorly represented by the city’s established elite institutions. For its first home, the young academy rented rooms above a milliner at 94 N. Second Street that included meeting space, a reading room, and a room to keep their growing specimen collection. The first major collection acquired by the academy, a large collection of minerals purchased from prominent local geologist and congressman Adam Seybert (1773–1825) in the summer of 1812, provided the basis for the first series of lectures for the members.

While the academy’s founders considered the creation and diffusion of knowledge about the natural world important for its own sake, they also enthusiastically embraced the idea that the study of natural science built character in urban young men and was a patriotic duty that would place the sciences in the young United States on an equal level with those in the Old World. Even though membership was restricted to only those people nominated by two current members, the academy continued to grow. By 1817 it became clear that if it were to take part in the international exchange of scientific theories and discoveries as well as specimens, the academy would need to publish a journal. Scottish-born geologist and academy member William Maclure (1763–1840), a generous donor of money as well as specimens and a large number of volumes for the library, championed the idea most strongly. He was so dedicated to public science education and cooperation that he bought the academy a printing press and housed it in his own home where the Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences was published for the first few years. The Journal, and later the Proceedings, became important natural science journals.

A History of Expeditions

In 1812, a mere month after its founding, the academy sponsored its first “expedition” to visit the zinc mines in nearby Perkiomen, Pennsylvania. As it grew in size and prestige it organized, sponsored, and staffed more expeditions, often in collaboration with the federal government and other institutions. Army topographer Major Stephen Harriman Long (1784–1864) led one such expedition in 1819 to the Upper Mississippi Valley, which included academy members Thomas Say and Titian Peale (1799–1885), to study and collect the area’s flora and fauna.

By the mid-nineteenth century, the academy’s amateur naturalists gave way to a more professional membership, reflecting a larger trend in American science. The academy continued to collect specimens from around the world through trade, purchase, donation, and sponsorship of expeditions of exploration. In 1834, it cosponsored an expedition to the mouth of the Columbia River with the American Philosophical Society. In 1838 academy members Charles Pickering (1805–78) and Titian Peale, along with several corresponding members, joined the four-year Wilkes Expedition, which explored and surveyed the Pacific Ocean and adjacent land.

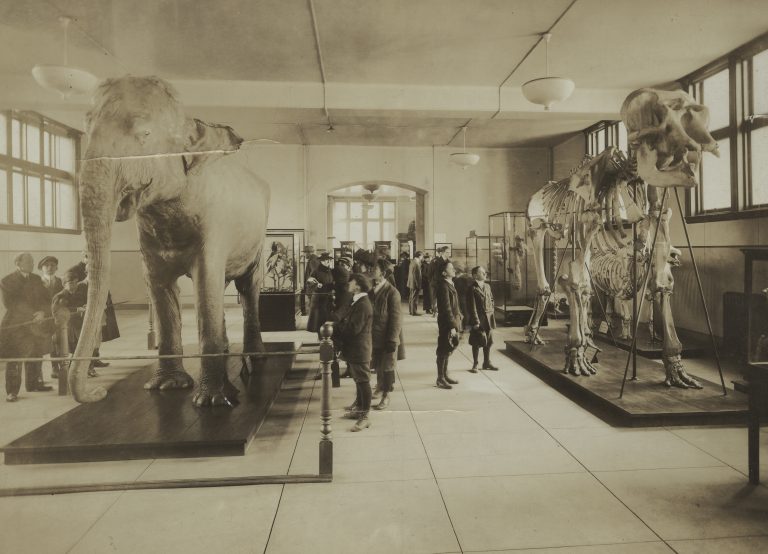

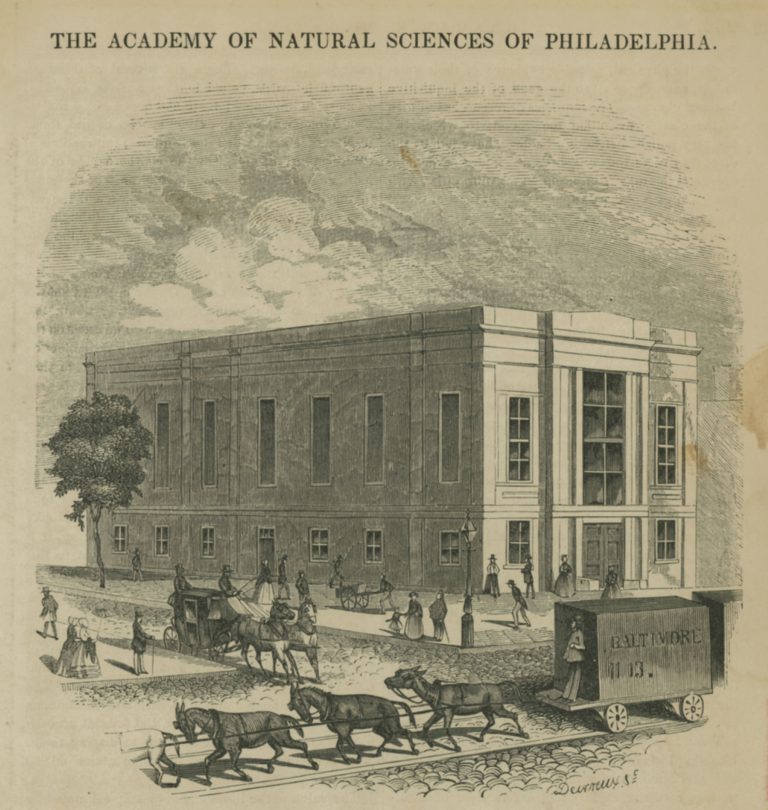

The academy’s collection grew quickly throughout the nineteenth century, forcing it to move five times to progressively larger buildings. In 1840 the institution moved to a new, fireproof building at Broad and Sansom Streets where it became one of the most modern, best-equipped natural history museums in the United States. It boasted, among other holdings, the world’s largest ornithological collection. The academy made its final move in 1876, constructing a new building at the corner of Race and Nineteenth Streets, a remote location that later became the heart of Philadelphia’s cultural district. The academy’s location was further enhanced by the creation of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway as the showpiece of the City Beautiful movement in 1917.

A Bent Toward Paleontology

Paleontological work preoccupied the academy during the late nineteenth century, thanks to men such as Joseph Leidy (1823–91) and Edward Drinker Cope (1840–97). Leidy trained as a medical doctor, taught anatomy at the University of Pennsylvania and later Swarthmore College, and was a curator at the Academy of Natural Sciences from 1846 until his death. He described some of the first dinosaur fossils in America and led the field of vertebrate paleontology for most of the nineteenth century. Leidy did some collecting locally, but relied largely on field naturalists such as Cope and Ferdinand Hayden (1829–87) to send fossils from the American West.

Following early successes by men such as Leidy and Hayden, the field of paleontology exploded, and the academy was at its center, not always for the better. The most brilliant and controversial of these later scientists was Edward Drinker Cope. A student of Leidy’s, Cope was talented and ambitious, and after the Civil War he embarked on a number of expeditions of the American West that sent huge numbers of paleontological specimens back to the academy. Unfortunately, Cope maneuvered himself into a petty, and sometimes violent, feud over access to fossil excavation sites, interpretations of specimens, and prestige with fellow paleontologist O.C. Marsh (1831–99) of Yale University, a feud dubbed by many historians as the “Bone Wars.” This feud had important consequences for the academy and Joseph Leidy. Outlandish stories of the feud published in the popular press sullied the academy’s reputation, and Leidy, disgusted by Cope’s behavior and tired of being caught in the middle of the feud, eventually abandoned paleontology in the West and turned his attention to other projects and helping local organizations, including serving as the president of the faculty and head of the museum at the Wagner Free Institute of Science of Philadelphia.

Twentieth Century and Beyond

By the turn of the century, study of natural science began to shift away from museums to university biology labs. However, the academy continued to sponsor expeditions to the Arctic, Asia, Africa, and Central America and conduct original research in several fields. Years before ecology, pollution, and conservation became topics of public debate, in 1947 the academy embarked on a research agenda to study aquatic ecosystems through its Department of Limnology, and in 1948 it established an Environmental Research Division. Throughout the twentieth century, the academy conducted important research in ecology and biodiversity on its own and in partnership with other area institutions.

In 2011 the academy became the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University when it formed an official affiliation with Drexel University. This partnership created a bridge between university-based biological research and museum-based natural history collecting. The relationship combined the institutions’ educational missions and resources and enhanced their ability to collaborate on natural and environmental science research. The affiliation facilitated, among other projects, creation of a joint Department of Biodiversity, Earth, and Environmental Science (BEES) dedicated to research and education in the fields of environmental science, ecology and conservation, biodiversity and evolution, geoscience, and paleontology.

The mission and motto of this new department, “Field Experience, Early and Often,” echoed the interests and ambitions of the founders of the Academy of Natural Sciences. By remaining true to the vision of its founders, America’s oldest institution of natural history remained relevant into the twenty-first century.

Matthew A. White is a Ph.D. candidate in the History Department at the University of Florida. His dissertation, “Patronage, Public Science, and Free Education: William Wagner and The Wagner Free Institute of Science 1855–1929,” was supported by grants from the Consortium for the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine (Philadelphia). He is also a museum professional with over twenty-five years of experience in museums of science, technology, and history, and is the Director of Education at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Postal Museum. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Academy explores ecological impact of natural gas drilling (WHYY, October 12, 2010)

- Insects 'dead and alive' at Academy of Natural Sciences' Bug Fest (WHYY, August 12, 2011)

- Drexel, Academy of Natural Sciences join forces (WHYY, October 26, 2011)

- Academy of Natural Sciences displays 200 years of curiosities — including 'Frankensquid' (WHYY, March 23, 2012)

- Animal sounds awaken at Academy of Natural Sciences (WHYY, July 7, 2012)

- Academy of Natural Sciences event has worms, crickets and more on the menu (WHYY, October 5, 2012)

- Academy of Natural Sciences puts itself on exhibit through dioramas (WHYY, April 14, 2014)

- Clergy devoted to science steadily add to Philly academy (WHYY, September 24, 2015)

- Natural history museums: a frontier for discovery, in danger (WHYY, March 31, 2016)

- Academy of Natural Sciences speaks out on climate change, water, evolution (WHYY, April 7, 2017)