Street Car Model

By John Hepp

Artifact

Drag across the screen to turn the object. Zoom to view details.

Read more below.

Essay

Drag across the screen to turn the object. Zoom to view details. Read more below.

[pano file=”Streetcar-VR-cm/FINAL.html” width=”570″ height=”325″]

Model of a nineteenth-century horse-drawn streetcar. (Philadelphia History Museum at the Atwater Kent, transferred from Philadelphia Transportation Company, 1942, Photograph by Sara Hawken)

This fascinating model of a horse-drawn streetcar links with the transportation history of late-nineteenth-century Philadelphia as well as the social and cultural history of the city over the last two centuries. Although we do not know precisely who produced this model or exactly when it was made, we can learn a great deal from studying it. The model was donated by the Philadelphia Transportation Company (PTC) to the then-new Atwater Kent Museum in 1942, just a year after the museum opened, and was likely produced for the PTC (or its corporate predecessor, the Philadelphia Rapid Transit) to illustrate improvements made in the city’s public transportation system over the previous century.

What can we learn about horse-drawn streetcars in Philadelphia from the model? First, in common with many mid-nineteenth-century horse-drawn streetcars, this is a single-ended vehicle with a driver’s platform at front and its only passenger access at the rear. This would have required a two-person crew (driver and conductor) and either a track loop or a turntable (not common) in order to reverse the vehicle at the end of its trip. On the front platform we can see the driver’s brake, which was used on most routes like a parking brake on a modern car, not to control the speed (the horses did that) but to hold the streetcar in place after the horses were detached. The fact that the car is pulled by two horses suggests it is a heavier or larger vehicle than streetcars pulled by one horse. The clerestory roof provided light and ventilation, as well as some welcome extra headroom over the aisle. We can even identify the car’s route because of the lettering on its side. Under the windows, the line is identified as the busy “Tenth & Eleventh” streets route (the “3” at center is the car number).

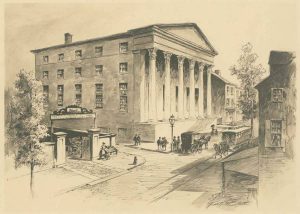

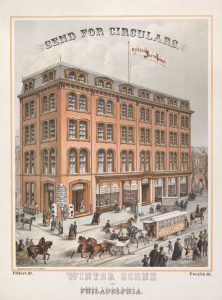

The horse-drawn streetcars represented by this model were the second of three transportation revolutions that transformed the residential patterns of Philadelphia in the nineteenth century for the middle and upper classes, who could afford the fares on a daily basis. The first transformation occurred in 1831, with the introduction of the horse-drawn omnibuses that allowed business owners and senior “clerks” (salaried workers) to live more than walking distance away from their firms the central business district (then centered on Second and Third streets). One of the omnibus routes (Jacob Peter’s Citizens Line) connected North Tenth Street with the business district and served a small part of the line that would become the streetcar route depicted by the model.

The horse-drawn streetcars of the late 1850s were an evolutionary change from the technology of the omnibuses, essentially omnibus bodies that traveled on rails laid in the streets instead of the street surface. This small change allowed for a smoother and a faster journey. Operators could cover an expanded range with fewer horses and cars. The final nineteenth-century transportation change came when these horse-drawn streetcars were replaced by electric trolleys in the 1890s. The route represented by this model was electrified on May 1, 1894, by the Electric Traction Company.

This model is a streetcar from the Citizens’ Passenger Railway Company, which initially ran from Tenth Street and Montgomery Avenue in North Philadelphia to Eleventh and Reed streets in South Philadelphia. Started on July 29, 1858, it was the third line in the city to begin service as a street railway. Above the windows of the model (you may have to zoom in to read the gold lettering on cream background) is emblazoned the northern terminus of this line as “Susquehanna & Dauphin” in North Philadelphia. This seeming geographic error (Susquehanna and Dauphin are parallel streets) actually helps to date with some precision the period depicted by the model. The Citizens’ Passenger Railway Company extended the northern terminus of the line to Colona Street (between Susquehanna and Dauphin streets) in December 1890, when it opened a new depot there to house the cars and horses. The route was converted to electric trolleys on May 1, 1894, so this model depicts the last three and a half years of the line’s use by horse-drawn streetcars.

Beyond the realm of public transport and real estate development, this model also has two interesting connections with the civil rights movement in Philadelphia. Initially, all of the city’s horse-drawn streetcar companies restricted ridership by race. Some required African Americans passengers to ride on the outer platforms, and others segregated entire cars by race. In 1867, following lobbying by African American civil rights activists William Still (1821-1902) and Octavius Catto (1839-71), a new state law ended transit segregation in Pennsylvania. Just three days later, however, on a Lombard Street car similar to the model, a conductor refused service to Caroline LeCount (1846-1923), an African American women and civil rights activist. She had the police arrest the conductor for violating the new law.

The long battle to end segregation was just beginning in the late-nineteenth century. Just two years after the PTC donated this model to Atwater Kent Museum, the company became subject to the largest labor action during World War II when its all-white unions struck for a week to prevent the PTC from hiring African American motormen and conductors. Because of the strike’s impact on war production, President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945) authorized the Army to take control of the transit system and five thousand troops were sent to Philadelphia to end the strike.

This simple model tells us a great deal about not just public transportation in Philadelphia in the nineteenth century after 1854 but everyday life in the city as well. Technological change was a constant; the horse-drawn streetcars that were emblematic of the Centennial City of 1876 were completely replaced by electric trolleys just twenty-one years later. These horse-drawn streetcars allowed the middle classes to leave the heterogeneous neighborhoods of the walking city and begin the development of what would later be known as streetcar suburbs.

Text by John Hepp, associate professor of history and co-chair of the Division of Global Cultures: History, Languages & Philosophy at Wilkes University in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, where he teaches American urban and cultural history with an emphasis on the period 1800 to 1940.