Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin (The)

By Rachel Lewis

Essay

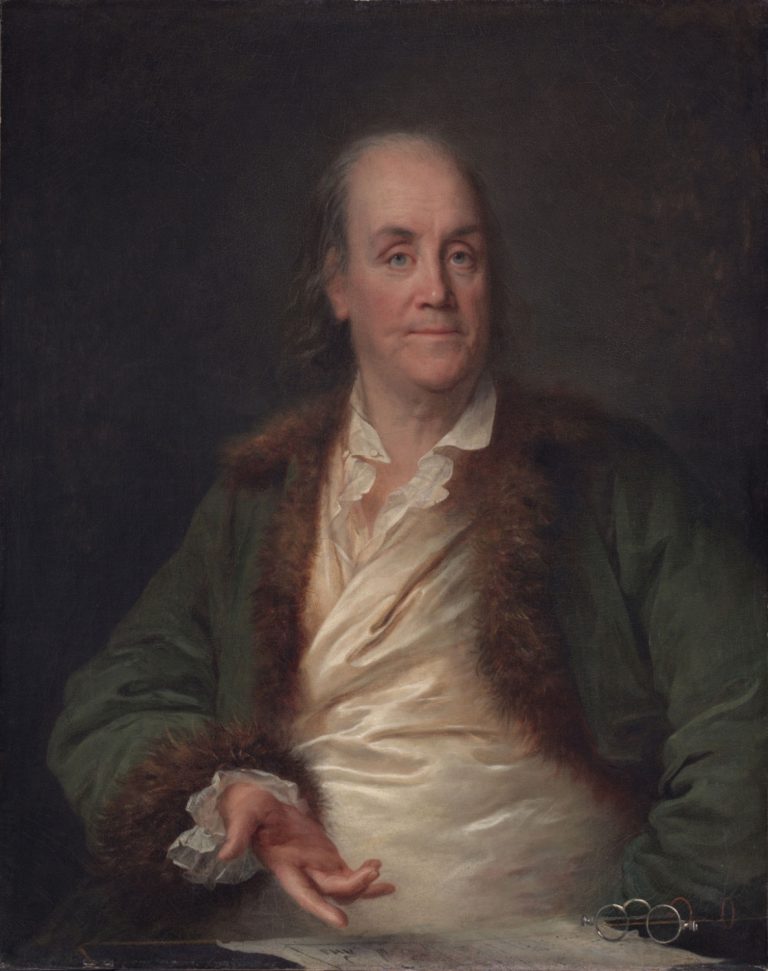

Over eighteen years, from 1771 until his death, Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) composed an unfinished record of his life’s tribulations and successes. Written in simple, often humorous language, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin offered readers in the new United States an accessible, exemplary narrative of American upward mobility. An integral thread in the fabric of Franklin’s history, Philadelphia is the setting for much of the autobiography and the site where Franklin composed portions of the work.

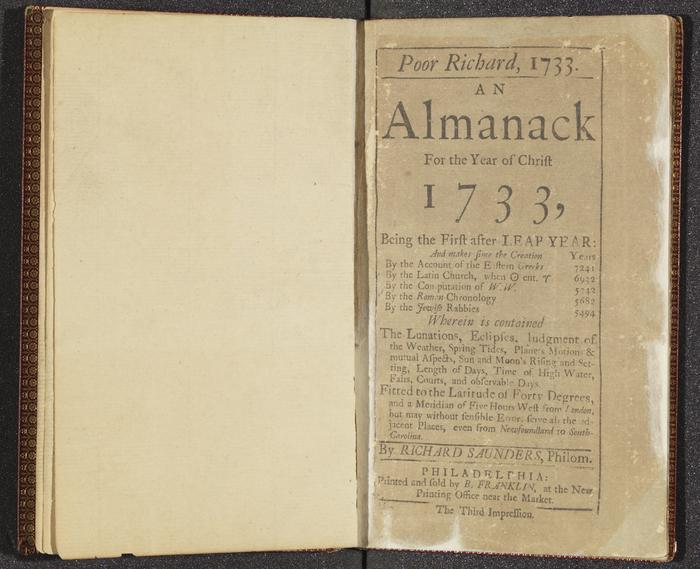

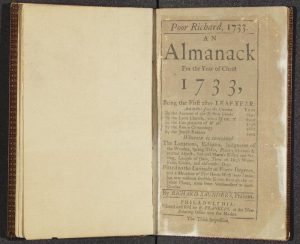

The Autobiography is arranged in four parts, each with a distinct purpose and tone, though Franklin intended for the work to be read fluidly as a whole. He began writing The Autobiography in 1771, during a stay in London of more than ten years as a mediator between England and the American colonies. Although Philadelphia was Franklin’s home, this trip marked his third sojourn to England. As a young man, Franklin traveled to England in 1724-26 to expand his knowledge of the printing trade and then returned to Philadelphia where he would seize production of The Pennsylvania Gazette from Samuel Keimer (c. 1688-1742) and begin Poor Richard’s Almanack. After thirty years of building his reputation as a printer and civic leader, Franklin also spent five years in England as a diplomat for the Pennsylvania Assembly beginning in 1757.

Written during the era of tension between the British and the colonies caused by seemingly arbitrary taxation, Part One of The Autobiography takes the form of a letter addressed to Franklin’s son William (1731-1814), then serving as royal governor of New Jersey. Franklin documents his childhood and adolescence, including his arrival in Philadelphia and his achievements in the printing business. He recounts his lineage, depicts his early life in Boston, and documents his apprenticeship with his brother James (1697-1735), a printer. After a dispute with his brother, at the young age of seventeen Franklin leaves his apprenticeship and resolves to move secretly to New York. There, he has trouble finding work and thus moves to Philadelphia.

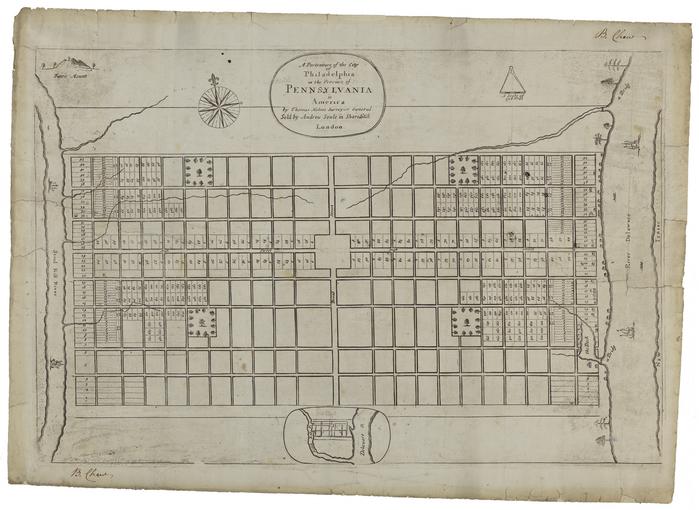

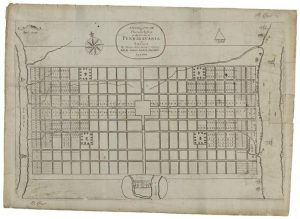

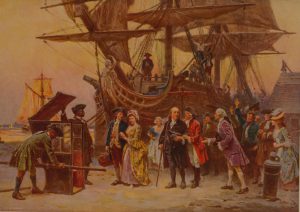

Part One chronicles Franklin’s eventful journey to Philadelphia, including his arrival by boat on October 6, 1723, after first docking in Burlington, New Jersey. Franklin calls attention to the contrast between his humble beginnings and entrance into Philadelphia and his eventual status as a businessman, civic leader, and public servant, addressing the reader directly: “You may in your Mind compare such unlikely Beginning with the Figure I have since made there.” Recalling the experience of arriving in his new city, he writes, “I knew no Soul, nor where to look for Lodging,” and then describes his first day in Philadelphia: “I walk’d up [Market] Street, gazing about, till near the Market House I met a Boy with Bread. I had many a Meal on Bread and inquiring where he got it, I went immediately to the Baker’s he directed me to in Second Street; and ask’d for Biscuit, intending such as we had in Boston, but they it seems were not made in Philadelphia.” Franklin’s first walk through the city took him west on Market Street to Fourth Street, then to Chestnut Street and Walnut Street, and “coming round found [himself] again at Market Street Wharf,” near where his boat was docked. At the end of his walk, Franklin entered “the Great meeting house of the Quakers near the market.” Although Franklin himself was not a Quaker, in The Autobiography he recounts the courtesy shown him by the Society of Friends: “I sat down among them, and, after looking round awhile and hearing nothing said, being very drowsy thro’ labour and want of rest the preceding night, I fell fast asleep, and continu’d so till the meeting broke up, when one was kind enough to rouse me. This was, therefore, the first house I was in, or slept in, in Philadelphia.”

Early Years in Philadelphia

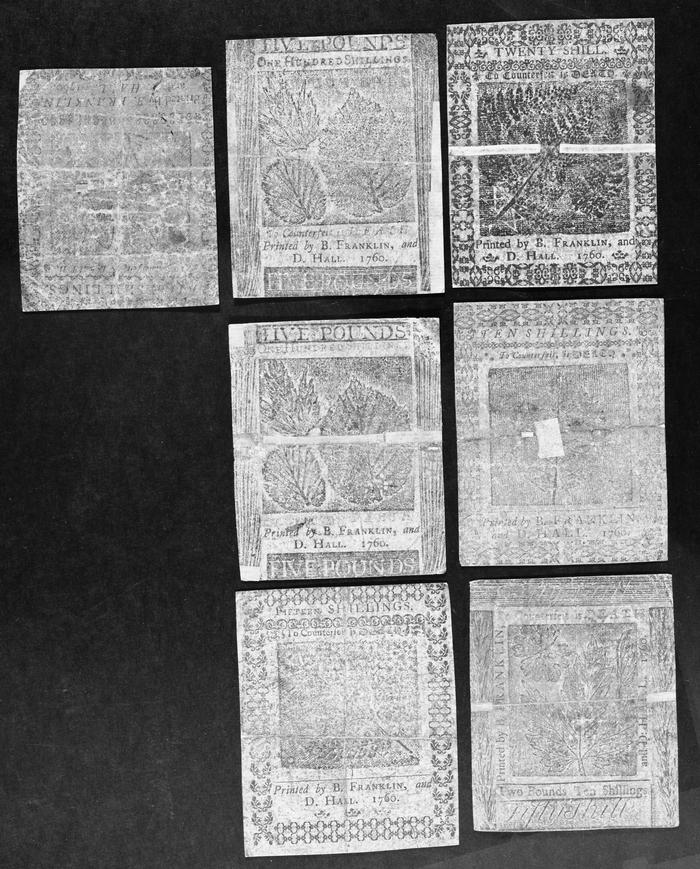

In Philadelphia, Franklin creates a life for himself. He attempts to find work as a printer and struggles with financial burdens. Eventually he finds lodging with John Read (1677-1724), a carpenter and building contractor, and begins to court Read’s daughter, Deborah (1707-74). Throughout his young adulthood, Franklin spends time in London studying the printing trade (1724-26). In Philadelphia Franklin establishes “The Junto,” an intellectual and philosophical conversation group, where he first introduces the concept of the lending library. Franklin finds work as a printer with Samuel Keimer and in 1729 buys his newspaper, The Pennsylvania Gazette, and eventually becomes the official printer for the Pennsylvania Assembly.

Franklin’s writings became associated with American mythologies of success early on. A contemporary of Franklin, his friend and fellow diplomat Benjamin Vaughan (1751-1835), read Part One of the memoir-in-progress in 1783 and noted that it exemplified the American ideal of upward social mobility: “All that has happened to you, is connected with the detail of the manners and situation of a rising people.” Vaughan’s statement, written in the aftermath of the American Revolution, speaks not only to Franklin’s achievement as an individual but also to the milieu in which he was writing and his audience of Americans in search of national and individual identities.

Franklin began writing Part Two of his autobiography in 1784 while serving as the United States minister plenipotentiary to France. This section is perhaps the best known of The Autobiography because it includes Franklin’s list of thirteen virtues for self-improvement: Temperance, Silence, Order, Resolution, Frugality, Industry, Sincerity, Justice, Moderation, Cleanliness, Tranquility, Chastity, and Humility. Franklin puts forth a plan to develop one virtue per week, intending to eventually perfect all thirteen virtues. Franklin’s virtues are meant to appeal to people of all religions, making his tenets for moral perfection a viable option for all people. Franklin’s emphasis on these thirteen virtues in The Autobiography has been cited as the impetus for self-help literature. Although inspirational for many, the message of self-improvement also drew negative criticism from such notable and varied figures as John Adams (1735-1826) and Abigail Adams (1744-1818), Mark Twain (1835-1910), and D.H. Lawrence (1885-1930), who found Franklin’s Puritan-like self-criticism to be inaccessible and improbable. Nevertheless, Franklin developed Puritan and Quaker influences into a message that mass audiences found instructive.

Franklin returned to writing his autobiography from 1788 to 1789, following his return from France in 1785 and his participation in the Constitutional Convention (May 25-September 17, 1787). Now in his eighties, Franklin in Part Three reflects on his life from 1730 through the late 1750s and highlights his involvement in politics, science, and publishing. At this time, Franklin also began to revise the already completed parts of The Autobiography manuscript.

Franklin as Publisher

In Part Three, Franklin describes his continuing involvement in the publishing industry with Poor Richard’s Almanack, first published in 1732 and subsequently for the next twenty-five years. Franklin uses the almanac and his newspaper, The Pennsylvania Gazette, to achieve his goal of educating common people. Franklin becomes clerk of the General Assembly of Pennsylvania and then deputy postmaster of Philadelphia, which allows him to distribute his Gazette by mail. In 1753, Franklin is appointed postmaster general of America. Franklin also publishes influential pamphlets, such as Plain Truth (1747), which outlines the need for colonial unity, and Proposals Relating to the Education of Youth in Philadelphia (1749), which leads to the creation of the Academy of Philadelphia in 1751 (in 1791, renamed the University of Pennsylvania). Franklin’s political agenda also includes advocating for the education of women. In Part Three, Franklin speculates on creating a political “Party of Virtue,” whose members would subscribe to his thirteen virtues as well as a compilation of virtues distilled from various religions. He also recounts his activities in science and invention, including the invention of the stove in 1742 and the notable 1752 kite experiment, which concluded that lightning and electricity are, in fact, one and the same. Culminating two decades of publishing, political, and scientific, advancements, the Pennsylvania Assembly appoints Franklin to the role of commissioner to England in 1756.

Part Four, written between November 1789 and his death on April 17, 1790, briefly documents Franklin’s journey to London from 1757 to 1762, where he petitions the Penn family for financial assistance on behalf of the Pennsylvania Assembly. In 1762, after the Penn family agreed to provide financial assistance to Pennsylvania for events transpiring in the colony, such as the French and Indian War (1754-63), Franklin returns to Philadelphia. The brevity of Part Four reflects Franklin’s declining health.

Franklin’s autobiography has a complex publication history. After Franklin’s death in 1790, his grandson William Temple Franklin (1762-1823) served as his literary executor. However, without his approval, unauthorized excerpts of The Autobiography appeared in Philadelphia magazines, Universal Asylum and Columbian Magazine (May 1790-June 1791), and American Museum (July and November 1790). The text made its debut as a book in Paris in 1791 as a French translation of Franklin’s manuscript of Part One, subsequently translated into German and Swedish. An English translation of the French edition, titled The Private Life of the Late Benjamin Franklin, was published in London in 1793. By the next year, American editions based on the retranslated edition circulated in New York and Philadelphia. More than two decades passed before William Temple Franklin released his own edition, Memoirs of the Life and Writings of Benjamin Franklin, in 1818. Although this edition became viewed as the standard version, it remained flawed; based on an unrevised manuscript, it did not include Franklin’s revisions of the text or Franklin’s Part Four. In 1828 Part Four made its debut in Mémoires Sur La Vie De Benjamin Franklin, a Paris edition written in French.

A Resurgence in Popularity

Finally, in 1868, seventy-eight years after Franklin’s death, all four parts of Franklin’s Autobiography appeared in an edition produced by John Bigelow (1817-1911), an American author, journalist, and diplomat. This edition, titled Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin used Franklin’s final manuscript. The autobiography’s resurgence in the late nineteenth century mirrored the publication of “rags-to-riches” young adult novels by Horatio Alger Jr. (1832-99), in which impoverished boys rise through hard work and determination to lives of middle-class security and comfort. The life of Benjamin Franklin fits into this schema that became known as the “Horatio Alger Myth.”

The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin has served as source material for Franklin’s many biographers and continues to be republished in various forms, including digital e-books and audiobooks. The manuscript of Franklin’s autobiography was made available digitally through the Huntington Digital Library. An accessible text, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin continues to be read widely by students and scholars in the twenty-first century.

Rachel Lewis is enrolled in the Rutgers University-Camden Graduate School, where she is pursuing her master’s degree in English and New Jersey Teacher Certification in secondary education of English. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2018, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Benjamin Franklin (American Philosophical Society Library)

- The Benjamin Franklin Papers (The Library of Congress)

- Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin. Edited by John Bigelow, 1868 (Hathi Trust Digital Library)

- The World of Benjamin Franklin (The Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin. Handwritten by Author, 1771-1789 (Huntington Digital Library)

- Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin. Edited by Frank Woodworth Pine, 2006 (Project Gutenberg)

- Histories of the University and Published Articles (University of Pennsylvania Archives and Records Center)