Market Street

By Stephen Nepa

Essay

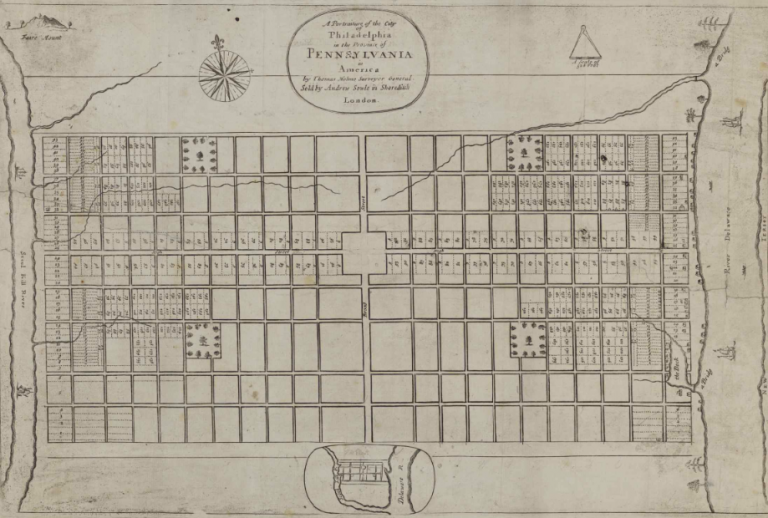

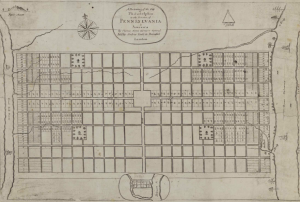

Market Street, one of Philadelphia’s primary east-west thoroughfares, originated in the 1682 city plan devised by William Penn (1644-1718) and Thomas Holme (1624-95) as High Street, one hundred feet wide and located at the longitudinal center of the city. Penn’s knowledge of plague and a devastating conflagration in 1660s London prompted the width of the street, which was intended to minimize the spread of disease and fire but also predetermined its central roles in Philadelphia’s geography, economy, and social fabric. Once called “America’s most historic highway,” over time Market Street extended nearly seven miles from Front Street to the city’s western boundary at Cobbs Creek. From there, it continued westward as Route 3 into Delaware and Chester Counties.

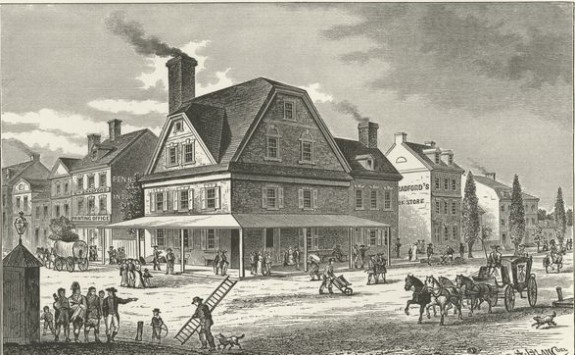

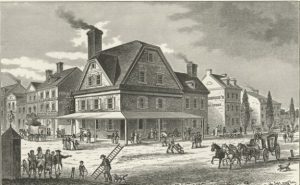

In eighteenth-century Philadelphia, the blocks of High Street closest to the busy Delaware River waterfront developed into the city’s business and civic center. Early institutions such as the Town Hall and Courthouse (built 1707), Christ Church (1744), London Coffeehouse (1754), and the Quakers’ Great Meetinghouse (1755), were built on or near High Street between Front and Second. By 1722, the city added a jail consisting of two stone buildings at Third and High Street, replacing the city’s original log-house jail on Second north of High. At a time of growing calls for law and order, as Philadelphia attracted people from around the world, the new buildings housed criminals and debtors separately and remained the city’s jail until the late 1770s.

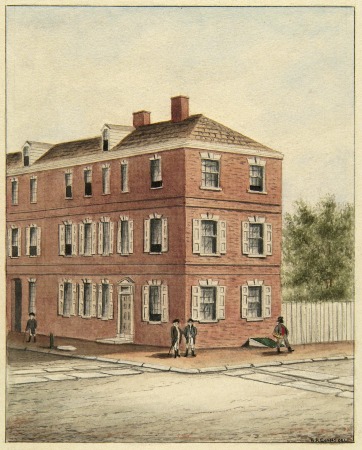

Notable Philadelphians resided on High Street, including Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) between Third and Fourth Streets; financier Robert Morris (1734-1806) between Fifth and Sixth, and builder Jacob Graff (1727-80) at Seventh Street. Newspapers, such as the Pennsylvania Herald and Pennsylvania Gazette, operated west of Third Street. Publishers and engravers, such as William Bradford (1719-91), John Dunlap (1747-1812), and Mary Katherine Goddard (1738-1816), who first published the Declaration of Independence with all signatories’ names, also opened businesses on High Street. Taverns complimented this burgeoning business district; the Indian King attracted Franklin’s “Junto,” a group of intellectuals dedicated to improving Philadelphia’s civic life. In 1729, Franklin’s close friend and Junto member Joseph Breintnall (?-1746) celebrated Market Street’s bustle in his poem “A plain description of one single street in this city.”

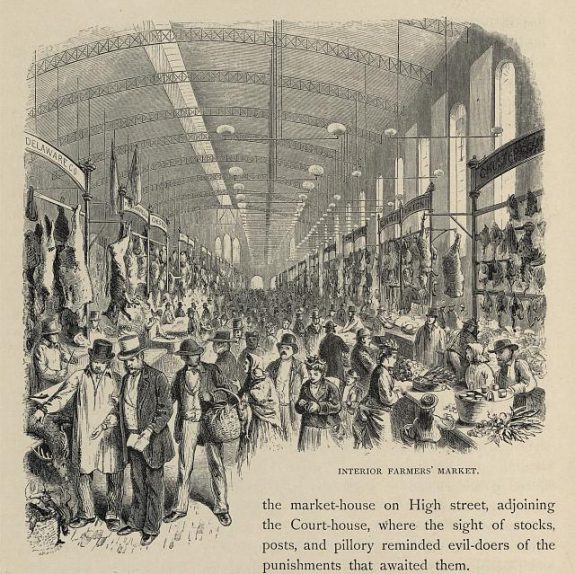

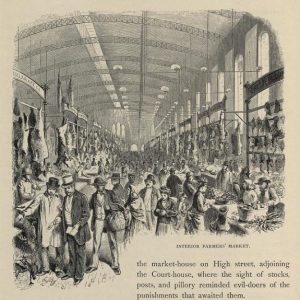

In 1745, construction began on the feature that gave the street a new name, first informally and then officially after 1854. The High Street Market, a headhouse with vendors’ stalls, initially stretched from Front to Second Streets, expanding to Third Street in 1759. Selling a variety of goods, the market, located in the street’s center, became the largest in the American colonies.

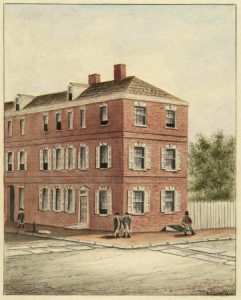

Revolutionary Hub

As tensions with the British monarchy and Parliament grew in the late eighteenth century, Market Street became a hub of revolutionary activity. Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) rented the top two floors of Jacob Graff’s house at Seventh Street, where in June 1776 he drafted the Declaration of Independence. Once hostilities erupted, the former prison at Third Street served as a military headquarters for the Continental Army and jail for British sympathizers. During the British occupation of the city during the winter of 1777-78, General William Howe (1729-1814), along with his mistress Elizabeth Loring (1752-1831), established quarters in the Governor’s Mansion (the Masters-Penn House, built in 1767) at Sixth Street. Following the British withdrawal in 1778, General Benedict Arnold (1741-1801), while living in the house, began plotting his notorious defection to the British Army. After the war, Robert Morris purchased and enlarged the property. In December 1783, George Washington (1732-99), en route from New York to Annapolis to resign his generalship, passed through Philadelphia to the sounds of church bells, cannon fire, and cheering crowds as his procession headed east along Market.

Market Street’s residential and commercial importance increased with Philadelphia’s designation as the nation’s capital. In 1790, Morris offered the use of his home to the new government’s executive branch, with President Washington residing there until 1797. John Adams (1735-1826) succeeded him, living in the house until the capital moved to Washington, D.C. in 1800. Following Adams’ departure, the home was acquired and converted into the Union Hotel by John Francis, who also owned the Indian Queen Hotel at Fourth and Market. A newer president’s mansion, built in 1792 at Ninth and Market’s southwest corner, never housed a sitting chief executive. Instead, the College of Philadelphia (later the University of Pennsylvania) occupied the building until 1829.

To entertain Philadelphians, in April 1793 John Bill Ricketts (1769-99) opened the country’s first circus on the city’s western edge of development, at Twelfth Street. With equestrian performances and acrobats, its amphitheater also served as a quarantine facility during that summer’s yellow fever epidemic.

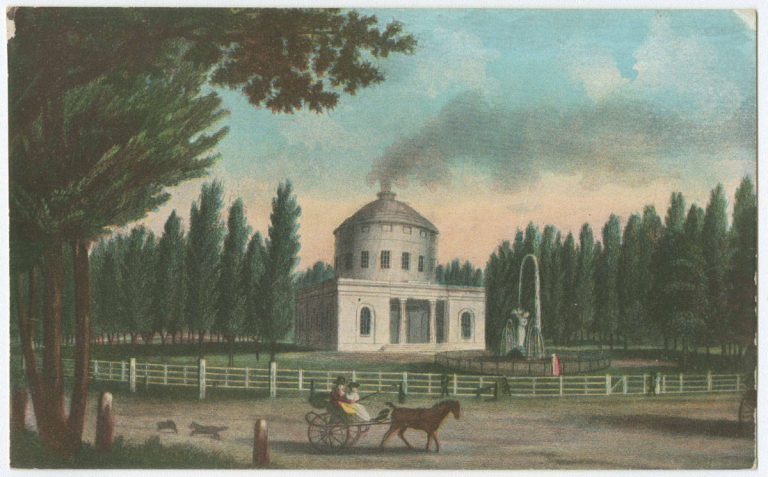

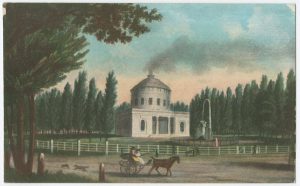

Commercial activities along Market Street diversified after 1800. These included apothecaries, shipping firms, new hotels, booksellers, silk purveyors, jewelers, and umbrella manufacturers. Noted chef M. Latouche operated a restaurant and oyster cellar at Fifth Street in the 1810s and appealed to the refined palettes of the city. Despite Penn’s hopes for Philadelphia’s westward expansion based on his city plan, little meaningful development occurred west of Twelfth Street as Philadelphians carved alleys into the streets nearest to the Delaware River. An exception occurred beginning in 1801, when architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe (1764-1820) oversaw construction of a Greek Revival-style pump house for the Philadelphia Waterworks in Centre Square, the ten-acre space originally conceived by Penn and Holme as the city’s administrative center. The Columbian Garden, a “pleasure garden” offering food and stage performances, opened in 1813 east of the pump house further making the square a popular gathering site and presaging its future as Philadelphia’s civic core.

Bridges Spur Development

With Philadelphia growing westward in the early nineteenth century, bridges replaced ferry crossings. Lobbying by Mantua resident Judge Richard Peters (1744-1828) led to Market Street’s first permanent bridge over the Schuylkill River, which opened in 1805. Designed by Timothy Palmer (1751-1821), the new connection—then the world’s largest covered bridge—spurred development in the rural areas west of the Schuylkill, previously the site of farms and potter’s fields. A number of lodging facilities, such as the Golden Fish and the William Penn Inn, opened along Market near the bridge, eager to capitalize on the increased traffic between the city and its western hinterlands. By the 1840s, this area of Market Street also contained numerous engineering and manufacturing concerns.

Philadelphia County’s twenty-nine townships consolidated in 1854, making the city by territory the fourth-largest in the western world. In 1858, an act of City Council officially changed the name of High Street to Market Street, which extended to the western boundary of the newly expanded city. As industry and population grew, so too did Market Street’s role as a transportation artery. Between 1859 and 1860, the High Street Market, which had expanded to Eighth Street and included additional sheds between Fifteenth and Seventeenth Streets, was demolished to make way for the Pennsylvania Railroad’s (PRR) trolley lines. The growing company, the largest transporter of Union supplies during the Civil War, opened Market Street streetcar terminals at Eighth and Eleventh Streets. In 1864, the PRR opened a terminal at Thirty-First and Market for its locomotives, which were banned from the city center. After the war, the PRR constructed its main Broad Street Station at Fifteenth and Market. Designed by Philadelphia architect Frank Furness (1839-1912), the Gothic-style station with its elaborate train shed (the world’s largest) opened in December 1881. To facilitate rail traffic and address capacity issues, a massive viaduct, later called the “Chinese Wall,” extended along Market from Broad Street Station west to the Schuylkill River.

Along with its increasing role in transportation, Market Street continued to mature as Philadelphia’s governmental and commercial hub. Following a voter referendum, work began in 1871 on a new city hall at Centre Square. Designed by John McArthur Jr. (1823-1890), the French Second Empire structure opened in 1901, standing as the world’s largest municipal building. Occupying the entirety of Centre Square, City Hall necessitated rerouting traffic around Market Street. Market Street was also emerging as the city’s primary retail corridor. In the same year as the 1876 Centennial Exhibition, clothier John Wanamaker (1838-1922) opened his first department store at Thirteenth Street. Catering to an upscale clientele and hosting seventy thousand customers its first day, Wanamaker’s Grand Depot also contained a restaurant, electric lighting, and elevators. Philadelphia’s “merchant prince” opened a larger, twelve-story store on the site in 1910, best known for its giant organ and bronze eagle statue. In 1893, Lit Brothers’ department store debuted at Eighth and Market and the following year, Indiana-based Gimbel’s arrived at Ninth and Market. In 1920, Gimbel’s sponsored the city’s first Thanksgiving Day parade, running from City Hall east to Ninth and Market. Strawbridge and Clothier, which started as a dry goods business at Eighth and Market in 1861, moved into its flagship building on the site in 1932. These stores, along with Snellenburg’s and Frank and Seder (both located on Market at Eleventh Street) offered the residents of greater Philadelphia exceptional shopping variety.

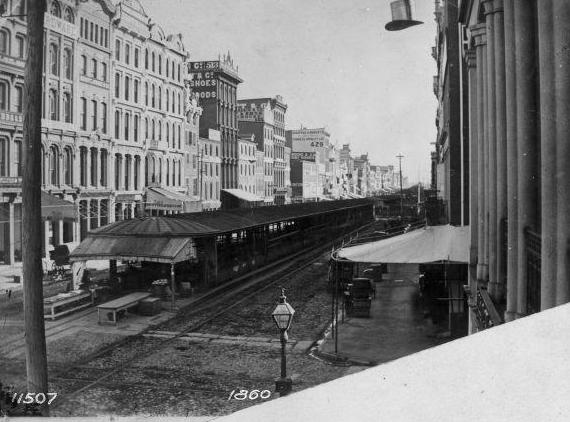

At the turn of the twentieth century, Market Street’s prosperity created congestion as pedestrians, bicyclists, horse-drawn vehicles, and electrified trolleys vied for passage. In 1905, service commenced on the Market Street Elevated (“El”) between Fifteenth Street and the Schuylkill River. The line was extended west to Sixty-Ninth Street in 1907 and east to Second Street in 1908 to complement the PRR’s Delaware River ferry terminal. These transit options both above and below ground reduced congestion on Market Street while allowing suburban residents speedier access to its theaters, stores, and offices. With connections to the north- and south-running trolley lines in West Philadelphia, the opening of the Market Street lines encouraged further residential growth between the Schuylkill River and Cobbs Creek. As the Great Migration commenced during World War I, the African American population of West Philadelphia grew considerably. By 1920, the population of West Philadelphia more than doubled from its 1900 levels and businesses clustering near train stations at Fifty-Second and Fifty-Sixth Streets pulled commercial activity away from Center City. In 1872, the University of Pennsylvania established its campus just south of Market Street; by 1900, the campus included over thirty buildings designed by some of the country’s most notable architects. In 1891, the Drexel Institute of Art, Science, and Industry (renamed Drexel University in 1970) opened two blocks south of Market at Thirty-First Street.

The High-Rise Arrives

Prior to 1890, few of Market Street’s buildings exceeded six stories. But with the arrival of the skyscraper, the corridor reached new heights. In 1892 the fourteen-story Betz Building, designed by William H. Decker (1856-1908), opened on the southeast corner of Centre Square. Later additions on Centre Square included the West End Trust Building (built 1898) and the Market Street National Bank (1929). Although the Great Depression stalled construction projects throughout Philadelphia, an exception was 1932’s Philadelphia Saving Fund Society (PSFS) tower, which opened on the former Ricketts’ Circus site. Designed by George Howe (1886-1955) and William Lescaze (1896-1969), it was the country’s first International-style tower and one of the most modern office buildings of its time.

Market Street transformed again in the years after World War II, especially west of City Hall. In the spirit of optimism that followed the Allies’ victory in World War II, optimistic Democratic reformers and urban planners conceived of a new image for the postwar city. In 1953, demolition of Broad Street Station and the Chinese Wall prepared the way for Penn Center, a series of office buildings with retail spaces and open-air plazas. The first project of its kind in a generation, it presaged the growth of the Market West corridor, which over the next sixty years saw the addition of dozens of office towers, hotels, and residential buildings. In 1985, real estate developer Willard G. Rouse III (1942-2003) brokered a deal with the mayoral administration of W. Wilson Goode (b.1938), allowing him to construct Liberty Place at Sixteenth and Market Streets. Completed in 1987, the office tower famously surpassed the city’s long-standing height restriction specifying that no building exceed William Penn’s statue atop City Hall. Transit development continued as well with the 1984 opening of the Center City Connector, a tunnel combining the former Reading and Pennsylvania Railroad lines and allowing more fluid access to retail and offices along Market Street.

In 1952, the Bandstand (later American Bandstand) television program debuted at Studio B at Forty-Sixth Street and Market. The show, hosted by Dick Clark (1929-2012) and featuring teenagers dancing to the latest popular music, went out to an estimated six million viewers before its national syndication in 1957. From then until the show’s 1964 relocation to Los Angeles, Bandstand placed Market Street (and Philadelphia) high in the nation’s cultural firmament. The campuses of Drexel University and the University of Pennsylvania continued to expand greatly around Market Street in the 1990s and early 2000s, while much of Market between Forty-Sixth Street and Cobbs Creek contained homes and small businesses such as cafes, laundries, discount retailers, and bodegas.

After World War II, Market Street’s retail offerings in Center City contracted sharply. Snellenburg’s, Frank and Seder, and Lit Brothers folded by the late 1960s. Gimbel’s left its Ninth Street store in 1977 to anchor the new Gallery Mall; its original building was demolished in 1979. Wanamaker’s was acquired in 1978 by a California company while Strawbridge & Clothier remained open until 1996. During the 1970s, many of Old City’s manufacturing interests also ceased operations, leading a wave of artists and creative professionals to transform factory spaces near Market Street into loft apartments. By the early 1990s, dozens of restaurants, bars, and clubs opened and challenged South Street for Philadelphia’s nightlife district. In the mid-2010s, the Philadelphia Inquirer and Philadelphia Daily News left their longtime quarters on North Broad Street and moved into Strawbridge’s building, the ground floors of which reopened in 2014 as discount merchant Century 21.

In the 2010s, Market Street continued to attract new construction projects, serve as the city’s main thoroughfare for parades and marches, and mark the official boundary between the northern and southern portions of Philadelphia’s numerical streets. Despite centuries of population shifts, commercial trends, and the rise and decline of many industries, Market Street’s importance to Philadelphia’s economy, social life, and mobility endured.

Stephen Nepa teaches history at Temple University, Rowan University, Moore College of Art and Design, and the Pennsylvania State University-Abington. A contributor to numerous books, journals, and documentary films, he received his M.A. from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and his Ph.D. from Temple University. He lives in Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Baby falcons born in tower of Philly City Hall (WHYY, May 21, 2013)

- $500 million revitalization planned for E. Market St. block (WHYY, March 19, 2014)

- Philly Love Note: The 'Love Letters' of West Philly's El riders (WHYY, September 4, 2014)

- Thousands turn out for 95th annual Thanksgiving Day parade, oldest in the nation [photos] (WHYY, November 28, 2014)

- The Gallery at Market East awaits $325 million makeover [photos] (WHYY, April 15, 2015)

- Reconstruction begins on north side of Philly's City Hall (WHYY, June 15, 2015)

- Market East property snags major new client (WHYY, September 11, 2015)

- Aramark moves up Market Street to build new world headquarters (WHYY, September 12, 2016)

- The Gallery: Past, Present, and Future (WHYY, October 23, 2018)

Links

- Misty Eyed for Market Shambles (PhillyHistory.org)

- Market Street: Fodder for Literary Legends (PhillyHistory Blog)

- Broad and Market Streets: the Intersection of Past and Future (PhillyHistory Blog)

- Populist Modern at Twelfth and Market (PhillyHistory Blog)

- The Gilded Mall Of Market Street: Gimbels Had It (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Chronometrical Obelisk Of Market Street: 1805-1953 (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Animal Plantation by the Market Street El (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Slaughterhouse 3000 (Market Street) (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- American Bandstand Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- London Coffee House Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Ricketts Circus Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Tracing the 'Chinese Wall' in Center City (Hidden City Philadelphia)