Automobiles

By Stephen Nepa

Essay

Since appearing in the 1890s, automobiles have in many ways shaped Greater Philadelphia’s history and geography. Initially a luxury item and later available on a massive scale, cars, while enhancing mobility, required billions of dollars in infrastructure, reordered the landscape of every town and city, and made indelible marks on the region’s architecture, culture, and economy.

The automobile, or “horseless carriage,” originated in Europe, where in the late 1800s companies such as Daimler-Benz, Peugeot, and Bentley produced limited quantities for niche customers. The first car in Philadelphia, a French import owned by merchant Jules Junker (c.1858-?), was registered in 1899. In the early 1900s, brewer Louis J. Bergdoll Jr., a racing enthusiast, purchased franchises for Philadelphia’s first Fiat, Packard, and Benz dealers. Bergdoll and other retailers formed the Automobile Dealers Association of Greater Philadelphia in 1904, the oldest group of its kind in the nation.

By the end of World War I, Philadelphia’s “automobile row,” anchored by the Albert Kahn (1869-1942)-designed Packard Building at Spring Garden Street and stretching along North Broad Street roughly to Girard Avenue, included car makers Ford, Cadillac, Studebaker, Hupmobile, and Oldsmobile. Cars also caught on in Wilmington, Delaware, where by 1916, the city’s 110,000 residents had fourteen car dealers to choose from. With varied selection and especially following the introduction of Ford’s Model T, regional car ownership grew rapidly, prompting journalist Christopher Morley (1890-1957) in 1919 to note that Philadelphia’s Market Street was “dimmed by the summer haze that is part atmospheric and part gasoline vapor.”

For those unable or unwilling to purchase an automobile, auto shows and races allowed people to view cars in terms of style and performance. Philadelphia held its first annual auto show in 1902, the nation’s third city (after New York and Chicago) to do so. Wilmington’s first show followed in 1916, with more than 100,000 viewing cars at the Hotel du Pont. Starting in the early 1900s, auto racing competitions were held throughout the metropolitan area. The Trenton Speedway at Hamilton, one of New Jersey’s first, began hosting races in 1900 on its half-mile dirt course. Following enlargement and paving in 1957, the track held NASCAR events until 1972. On an eight-mile, oiled gravel track in Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park, the Quaker City Motor Club (whose members included prominent businessmen) ran races from 1908 through 1911. Though popular and drawing spectators from Canada to Paris, the races angered Philadelphia patricians who felt speeding cars disturbed the park’s tranquility. Delaware’s Wawaset Park hosted New Castle County’s first auto races in 1915. Through the 1920s, Wildwood, Cape May Court House, and Longport, New Jersey, held races on the beach during summer months. Other venues included Delaware’s Dover Downs (opened 1969) and Long Pond, Pennsylvania’s Pocono Raceway (opened 1971), both of which hosted NASCAR races into the twenty-first century.

Broad Street Paved, 1894

The advent of the automobile required creative responses from cities formed long before its arrival, including street paving, road building, and traffic control measures. Paving in Philadelphia commenced in 1894 (Broad Street was the first), yet automobile congestion on the city’s narrow blocks led over time to the designation of one-way streets and the installation of kerosene-lit traffic signals (requiring human operation) in the 1910s. Although landscape architect Jacques Gréber’s (1882-1962) 1917 proposal to alleviate gridlock through an ambitious series of diagonal boulevards across Philadelphia’s rectilinear grid never materialized, other built arterials served the purpose, including Northeast (later Roosevelt) Boulevard and Fairmount (later Benjamin Franklin) Parkway. While they may not have alleviated traffic, they increased outlying property values and spurred suburban growth. The 1926 opening of the Delaware River (later Benjamin Franklin) Bridge allowed drivers easy connections between Center City and South Jersey. In Delaware, Pierre S. du Pont (1870-1954), impatient with poor road quality on his daily commute from Longwood, personally financed improvements of the Kennett Pike (SR 52) to connect central Wilmington with suburban Chester County, Pennsylvania.

Increased car ownership prompted safety concerns. In 1904, due to steam-powered cars’ emissions and possible explosion, Philadelphia initiated the Bureau of Boiler Inspection, a forerunner of vehicle inspection. With rising car fatalities in the 1920s, safety campaigns in Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey led to mandatory vehicle inspection. Penalties for speeding and other violations were addressed in traffic courts. Though Philadelphia in the mid-1920s created one of the country’s first municipal traffic courts, smaller towns devoted specific days of the week for violations. During Prohibition, Philadelphia’s director of public safety Maj. Gen. Smedley Darlington Butler (1881-1940) set up military checkpoints to curtail bootlegging and introduced armored squad cars for the city’s police force. In Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, the Farmers Anti-Automobile Association, angered by speeding cars, formed in 1910 to set strict rules for drivers using their rural roads.

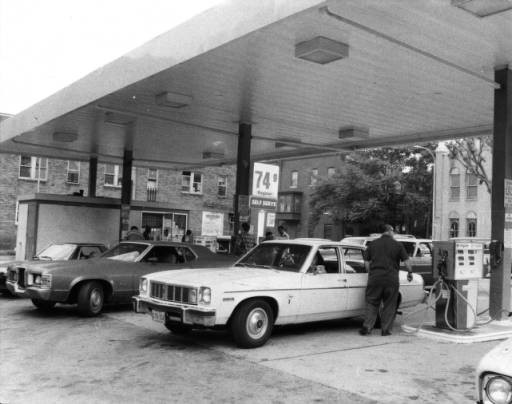

Greater Philadelphia’s motorists required auto-related businesses such as gas stations, repair shops, and parts suppliers. Due to environmental hazards, gas stations were located in urban industrial areas prior to 1920. Yet with roads delivering cars and trucks beyond cities, stations followed. The Lincoln Highway, the nation’s first interstate road exclusively for cars, opened in 1925 and passing through Greater Philadelphia, prompted local oil companies such as Sun and Atlantic to open stations along the route. In 1907, Max Paul, an Old City bicycle repairman, opened one of Philadelphia’s first car repair shops at 7018 Woodland Avenue; in 1968 Paul’s two sons, who inherited the business, opened the city’s first Toyota dealership. And in 1921, Pep Auto Supplies opened its first store in Philadelphia. Renamed “Pep Boys” two years later, the company operated 40 stores in the region by the mid-1930s.

World War II directly impacted Greater Philadelphians’ automobility. Following Japan’s invasion of the Dutch East Indies (where the U.S. procured ninety per cent of its rubber supply), local junkyards were scoured for used tires. Additionally, the Office of Price Administration (OPA) stipulated that all “nonessential drivers” own no more than five car tires. In 1942, the federal government halted all new car manufacturing, established speed limits of thirty-five miles per hour to reduce tire wear, and instituted gasoline rationing. During the war, Philadelphia became notorious for bootlegged fuel. Other measures, such as carpooling and using mass transit, helped conserve valuable resources. Car companies also contributed to the war effort, with Ford’s Chester, Pennsylvania, facility assembling tanks and military vehicles and General Motors’ West Trenton plant building torpedo bombers.

Car Manufacturing Arrives

Greater Philadelphia experienced dramatic automobile-related change after 1945. As suburbanization increased, car manufacturers followed. GM and Chrysler opened new factories in Elsmere, Delaware (1947), and Newark, Delaware (1952), respectively. The physical decay of cities such as Philadelphia and Trenton (and their narrow streets) prompted many in the region to move to car-dependent suburbs. At the same time, parking lots and garages were built throughout those cities’ downtowns for suburban commuters. Yet not all garage plans materialized. In 1947, the newly created Center City Residents’ Association (CCRA) defeated a proposed garage for beneath Philadelphia’s Rittenhouse Square. In 1950, City Council created the Philadelphia Parking Authority to manage lots and garages, but the agency did not oversee on-street parking until 1983.

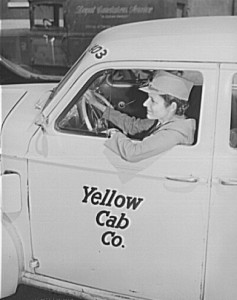

Driving also led to decreases in mass transit ridership. National City Lines, a shell company created by General Motors, Firestone Tires, and Standard Oil, purchased majority stakes in many U.S. trolley companies, a move intended to phase out the systems in favor of the automobile. Along with National City Lines’ acquisitions, inexpensive gas, transit strikes in the late 1940s, and bus lines that provided access to suburbs allowed the automobile to dominate the postwar landscape.

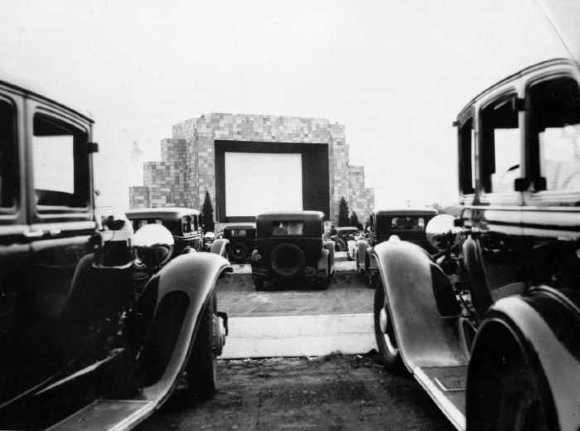

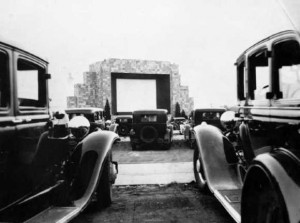

With passage of the 1956 Interstate Highway Act, the area’s towns and cities were connected by high-speed expressways, including the Schuylkill Expressway (I-76), the Delaware Expressway (I-95), the Atlantic City Expressway, and the New Jersey Turnpike. New suburbs accessible by highways, such as Levittown, Pennsylvania; Cherry Hill, New Jersey; and Sherwood Park, Delaware, contained slow-speed, curvilinear streets and driveways for homes. Graced further by shopping malls, drive-through restaurants, and drive-in movie theaters, Greater Philadelphia’s postwar suburbs reflected the region’s continual embrace of the car.

As Greater Philadelphia approached the digital age in the 1980s, highway agencies in New Jersey and Pennsylvania proposed electronic toll collection to reduce bottlenecks. In the early 1990s, the “E-Z Pass” system went into operation on selected highways; by 2015, all area bridges and toll plazas used the system. In the twenty-first century, automobiles, while still the region’s preferred method of travel, were challenged by car- and bike-sharing programs in central cities and suburbs, transit-village development, and increased service offered by SEPTA, PATCO, and NJ Transit. As reliance on personal digital devices increased, leading to several fatal accidents, New Jersey and Pennsylvania in the 2010s began issuing penalties for “distracted driving.”

While bringing both positive and negative results, automobiles and their many related business allowed Greater Philadelphia’s residents and visitors personal freedom, faster mobility, and a romantic attachment to the open road.

Stephen Nepa received his M.A. from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and his Ph.D. from Temple University. He teaches history and American studies at Temple University, Moore College of Art and Design, and Rowan University. He also has appeared in the Emmy Award-winning documentary series Philadelphia: the Great Experiment. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- Britannica's History of the Automobile

- Americans Adopt the Auto (Smithsonian's America on the Move Exhibit)

- A Temple to the Gasoline Gods at Broad and the Boulevard (PhillyHistory Blog)

- The Battle for Gasadelphia (PhillyHistory Blog)

- The Toughest Little Hut in Logan Square (Hidden City)

- Collecting Paper Cars: Z. Taylor Vinson's Collection of Autombile Advertising (Hagley Museum and Library)

- Automobile Engineer: Joseph Ledwinka (Hagley Museum and Library)

- Simeone Foundation Automotive Museum (WHYY Friday Arts)

- Historic Callowhill auto building to be demolished (Curbed)