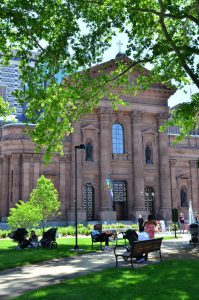

Cathedral Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul

Essay

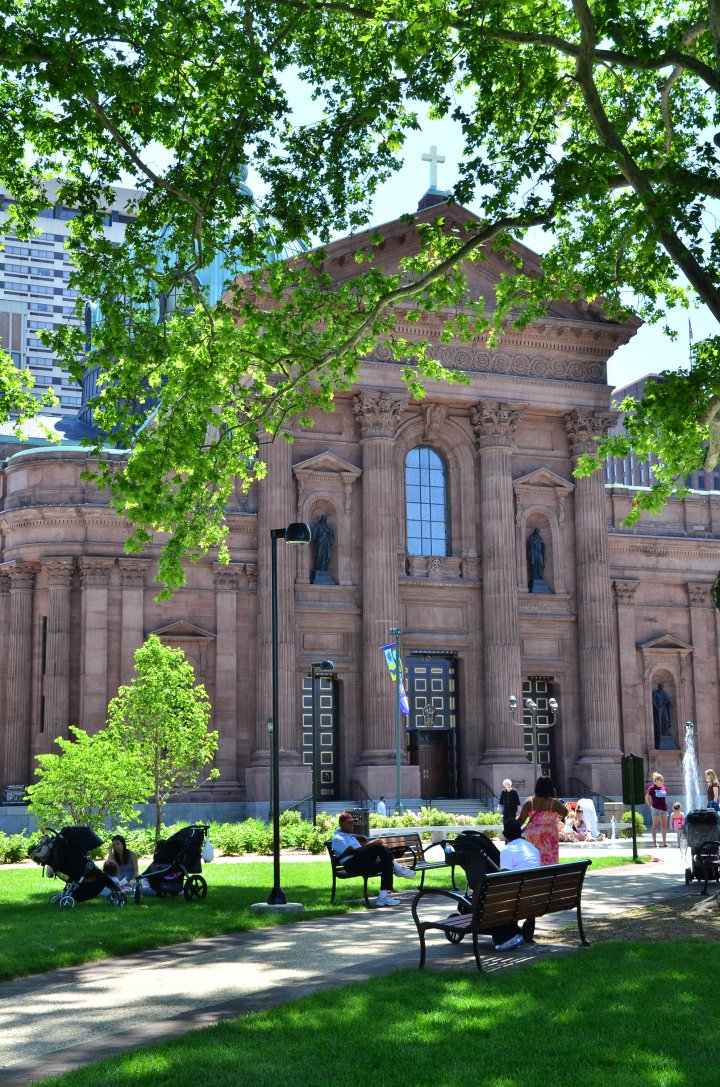

Established in 1846, the Cathedral Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul at Eighteenth and Race Streets became the principal church and center of Catholic life for the clergy and faithful of the Philadelphia archdiocese. During a turbulent era of immigration and anti-Catholic nativism, Bishop Francis Patrick Kenrick (1796-1863) desired a “common church of the whole diocese,” which at the time included Pennsylvania, Delaware, and parts of New Jersey. He envisioned the cathedral “on the front of a large public square,” where it would be a meeting ground for the local and universal Church, a place of liturgical practice for seminarians and professors from the nearby Theological Seminary of St. Charles Borromeo, a base for missionaries operating throughout the diocese, and “a splendid ornament” for Philadelphia.

A cathedral is the bishop’s church, where he presides, teaches, and conducts worship for the Christian community of his area of ecclesial jurisdiction. Basilicas, according to the 1989 Vatican document Domus Ecclesiae, “stand out as a center of active and pastoral liturgy.” They indicate a special bond of communion with the pope, his concern for the faithful of all nations, and the strengthening of ties between the local and the universal Church.

Philadelphia’s new cathedral acquired its site on Logan Square when Marc Anthony Frenaye (1783-1873), the diocese’s financier and a refugee from the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804), purchased the plot from the Farmers’ Life and Trust Co. of New York. Frenaye also purchased the four-story house that originally stood on the site, which subsequently became the cathedral rectory. Philadelphia architect Napoleon LeBrun (1821-1901), whose major work included St. Patrick’s on Rittenhouse Square (1839) and later the Academy of Music (1857), executed initial designs for the Roman-Baroque style church modeled on Rome’s San Carlo al Corso. Scottish-born Philadelphia architect John Notman (1810-65), who later built St. Clement’s (1856-59), contributed its Italian Renaissance Palladian façade.

Cornerstone Laid in 1846

Construction on the imposing sandstone structure was slow, given the challenges of meeting the spiritual, pastoral, and social needs of Philadelphia’s expanding Catholic population and organizing the Philadelphia diocese. During the era of increasing Irish-Catholic immigration and diocesan expansion in the mid to late 1840s, Kenrick juggled lack of funds, debt, and initial opposition from priests and laypeople to the idea of building a new cathedral. Already suffering a shortage of priests and churches, they were concerned about maintaining their own parishes and the cost of rebuilding churches destroyed during the nativist riots that took place in Philadelphia in 1844. Leading up to 1845, some objected that Catholicism’s growth in Philadelphia did not yet warrant building a church exceeding any other church in the city in both cost and physical proportion. Some also considered the proposed site to be too far west from the city center and the bishop’s then-cathedral, St. John the Evangelist on South Thirteenth Street. Nonetheless, eight thousand people witnessed Kenrick lay the cornerstone on September 6, 1846. Laying the cornerstone for a new Catholic church is an elaborate ritual, in which the bishop explains its ecclesial and theological significance while also soliciting the faithful’s financial support. Catholics organized a system of block collections by parish to raise the requisite funds.

After Kenrick became Archbishop of Baltimore in 1851, construction of the church continued under Bishop John Neumann (1811-60) and Archbishop James Frederick Wood (1813-83). It proceeded through most of the Civil War, even while Philadelphia’s industrial importance in the conflict and continuing financial difficulty meant that church officials struggled to retain workers. The interior remained largely unembellished while details filled in slowly. Italian-born “artist of the United States Capitol,” Constantino Brumidi (1805-80), known for his mural The Apotheosis of George Washington (1865), executed five oil paintings for the ceiling dome in 1863: The Assumption of the Virgin into Heaven, and four of the evangelists Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John were in place for the Cathedral’s dedication—and opening for services—on November 20, 1864. Philadelphian Edwin F. Durang (1829-1911) designed a marble high altar, placed in 1883-84 before the church’s consecration in 1890. By the mid-twentieth century, it boasted interior and exterior renovation work by Philadelphia’s Henry Dandurand Dagit (1865-1929), and the firms of Daprato (Chicago) and Eggers and Higgins (New York), among others.

During the building’s construction, the Friends of the Cathedral society saw its potential for evangelization in the surrounding neighborhood, which was becoming both Protestant and wealthy. The cathedral became the base of operations for several Catholic civic organizations, such as the Total Abstinence Society, the Ladies’ Society, and Cadet Societies for boys and girls. During the early twentieth century, construction of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway placed the Cathedral amid a developing museum district. The building merited placement on the National Register of Historic Places in 1971 on the basis of the architectural significance of the work by LeBrun, Notman, and Brumidi and the religious/philosophical significance of its roles as “the center of Catholic life of Philadelphia” and longtime church of St. John Neumann—the first canonized U.S. bishop, whose cause for canonization was underway at the time.

The cathedral has continued to play an active role in the lives of Philadelphia’s Catholics. In the summer of 1976, Philadelphia’s celebration of the American Revolution’s bicentennial coincided with the Forty-First International Eucharistic Congress (August 1-8) held in the city. Following the congress, at the request of then-archbishop John Cardinal Krol (1910-96), Pope Paul VI (1897-1978) designated the Cathedral of SS. Peter and Paul a basilica, solidifying its role as the meeting ground between the Philadelphia archdiocese and the universal Church that Bishop Kenrick had originally intended: during a papal visit in 1979, Pope John Paul II (1920-2005) prayed in the cathedral and celebrated Mass in Logan Circle; in 2015, Pope Francis (b. 1936) publicly celebrated Mass at the cathedral and on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway during the World Meeting of Families. The Cathedral Basilica of SS. Peter and Paul has remained an architectural focal point for Philadelphia and a major site of worship, devotion, and Catholic identity.

Wendy Wong Schirmer, a historian of Early America and U.S. foreign relations, received her Ph.D. from Temple University. She is working on a book project that examines the relationship between print culture, neutrality in the Early Republic, and the politics of slavery. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University