Cemeteries

By Stephen Nepa

Essay

Cemeteries have been integral features of the Philadelphia-area landscape since the earliest European settlements of the mid-1600s. Over the centuries, and in tandem with developments such as epidemics, immigration, industrialization, war, and suburbanization, the region’s cemeteries matured from small, private grave sites, potter’s fields, and church burial yards to rural cemeteries, national cemeteries, and memorial parks. From the colonial period to the present, cemeteries reflected the area’s religious, economic, and cultural diversity. As Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) once remarked, “Show me your cemeteries and I will tell you want kind of people you have.”

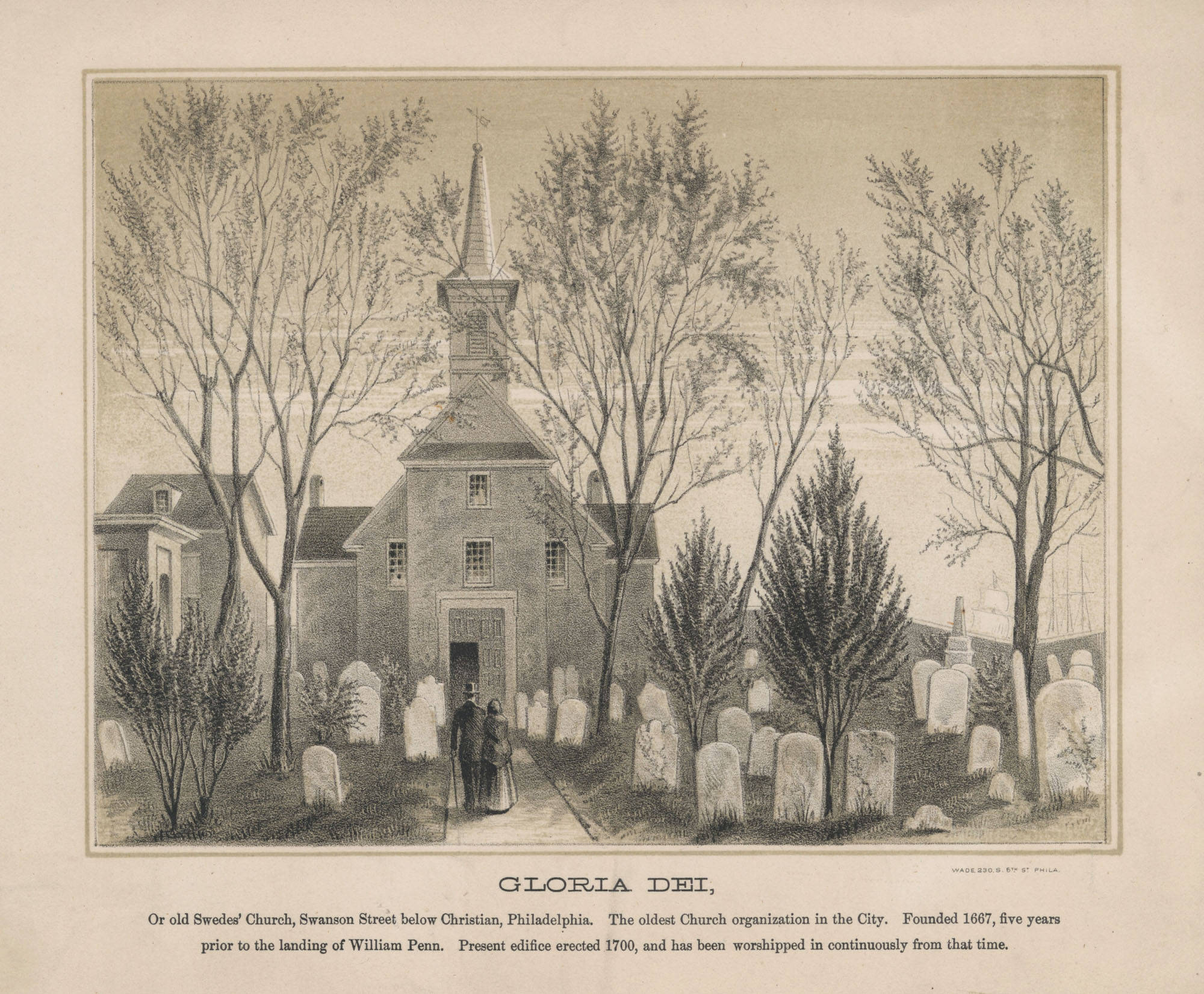

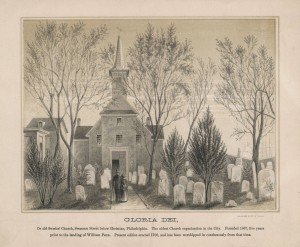

Prior to Philadelphia’s inception in 1682, Swedish colonists settled along the Delaware River roughly from New Castle, Delaware, north to the future site of Penn’s Landing. At Fort Christina just east of Wilmington, Delaware, they erected a burial yard in 1642, believed to be the area’s first of European design. The first European church cemetery opened in 1646 on Tinicum Island southwest of the future site of Philadelphia International Airport; floodwaters from the Delaware River submerged the site within a decade. Determined to prevent future damage to their grave sites, the Swedes in 1677 erected the Gloria Dei (“Old Swedes”) Church at present-day Christian Street and Columbus Boulevard. The burial ground in its adjacent yard is Greater Philadelphia’s oldest surviving cemetery. In 1698, Wilmington’s Holy Trinity Church was erected next to the former Fort Christina burial ground. Prior to its closing, Holy Trinity’s cemetery contained 15,000 burials, including members of the prominent Bayard, Montgomery, and Du Pont families.

During the colonial and early national periods, one’s burial place denoted religious affiliation and class distinction. When Quaker families arrived in the 1670s and 1680s, they established plain, unadorned burial yards next to their meetinghouses. In towns such as Cape May Court House, Camden, Trenton, Salem, and Burlington, these emerged as South Jersey’s earliest formal cemeteries. When William Penn (1644-1718) and surveyor Thomas Holme (1624-1695) devised the Philadelphia grid system, their plan included four squares for public use, yet no officially designated cemeteries. Their omission stemmed from the belief that burial grounds were sectarian responsibilities.

Quaker Graves Were Simple

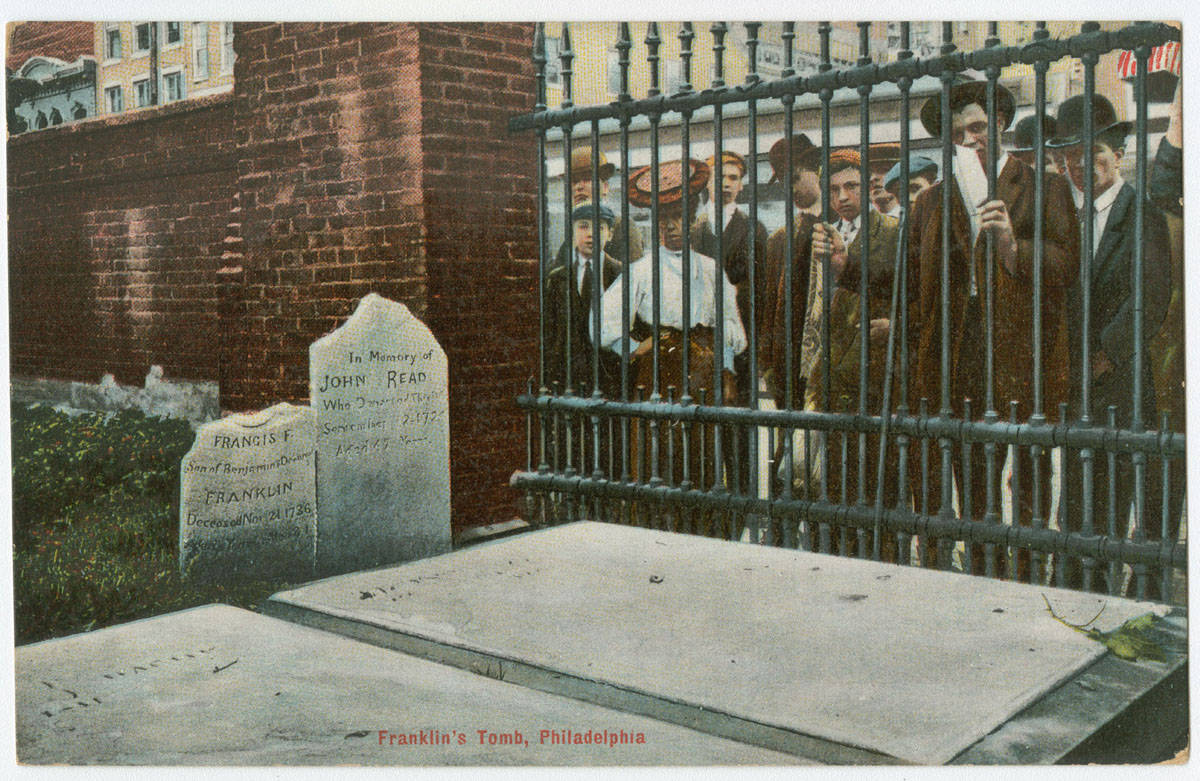

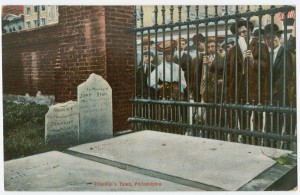

Penn’s Quaker faithful interred their dead behind the Arch Street Meetinghouse without official ceremony or elaborate markers. Conversely, Philadelphia’s Anglicans, who opened cemeteries at Christ Church (est. 1695, Second and Market Streets) and St. Peter’s Church (est. 1761, Third and Pine Streets), fashioned headstones and markers of considerable ornamentation. In 1719, Christ Church’s leaders purchased a tract at Fifth and Arch Streets (then the city’s outskirts) to accommodate more interments. Over time, Christ Church’s graveyard became the city’s most elite, containing the remains of Franklin, Francis Hopkinson, Benjamin Rush, and several prominent Philadelphians. Other Protestant sects, including Lutherans, Methodists, and Moravians, also established cemeteries next to their houses of worship. Wilmington’s first Methodist cemetery, located next to Old Asbury Church, opened in 1789, while the city’s Presbyterian Church contained a graveyard dating to the 1740s.

During the 1700s and early 1800s, increasing numbers of Jews, Catholics, and people of African descent arrived, bringing with them funeral rites and burial practices. Due to religious and/or racial differences, these groups established their own churches and cemeteries or, if lacking financial means or accessibility, were interred in one of the area’s potter’s fields. In 1740 after the death of his son, Philadelphia merchant Nathan Levy (1704-1753) petitioned proprietary governor Thomas Penn for a private burial site. With his request granted, Levy established Mikveh Israel, the city’s first Jewish cemetery, on Spruce Street between Eighth and Ninth Streets. Levy himself was interred there in 1753. In 1733, Philadelphia Catholics erected St. Joseph’s Church on Willings Alley between Third and Fourth Streets; until 1759, its burial yard was the only Catholic cemetery in the city. In New Jersey, Catholics established churches with adjacent burial grounds in Trenton and Camden between 1801 and 1814.

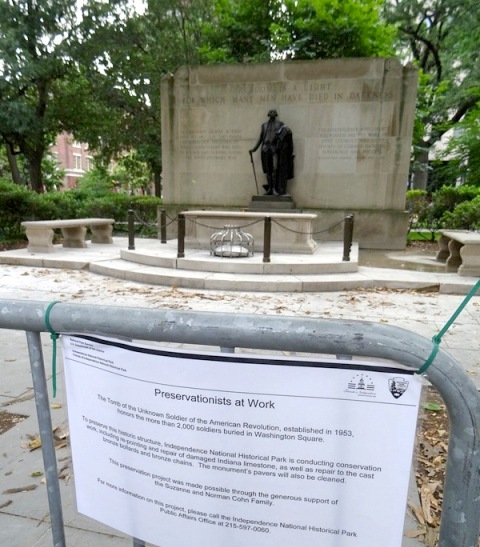

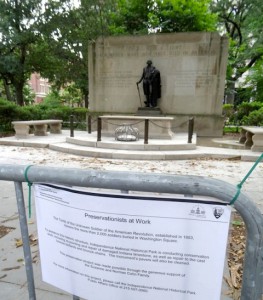

Due to growing class differences, racial intolerance, and the existence of human bondage, many Philadelphians were interred in the city’s public squares that also functioned as potter’s fields. Southeast Square (renamed Washington Square in 1825) served as a “Strangers Burial Ground” for Catholics, the indebted poor, prisoners, free and enslaved Black persons, soldiers from the Revolutionary War, and victims of the 1793 yellow fever epidemic. Northwest Square (later renamed Logan Square) was used as a potter’s field until the late 1830s. For several decades, Philadelphia’s cemeteries would not accept Black interments. In 1810, Mother Bethel AME Church, the nation’s oldest African American church, purchased a plot in present-day Queen Village as a private burial ground, which remained in use until 1864. In 1910, the Philadelphia Department of Recreation turned the dilapidated site into the Weccacoe Playground, and in 2014 hearings were held by the city over concerns about the playground being above a historic cemetery. Of the more than 150 cemeteries created in the region during the colonial period, fewer than twenty survive in the present day.

“Garden” Cemetery Concept Arrives

Following the American Revolution and Philadelphia’s tenure as the national capital (1790-1800), the “rural” or “garden” cemetery concept arrived from Europe. Modeled on Paris’ Père-Lachaise (est. 1804), which was designed to relieve the overcrowding of existing cemeteries, this new design essentially beautified death through picturesque landscapes and ostentatious monuments. As many Western metropolises weathered disease epidemics in the late 1700s and early 1800s, it also was thought that removing the dead beyond the city would prevent the spread of miasmas and plagues of malaria, yellow fever, or cholera. Mt. Auburn Cemetery (est. 1831) in Cambridge, Massachusetts, was the United States’ first rural cemetery, incorporating Arcadian aesthetics and imposing statuary with notions of privacy and reflection.

Determined to bring such refinement to Philadelphia, in 1836 real estate investor and horticulturalist John Jay Smith (1798-1881) and his partners created Laurel Hill Cemetery. Inspired by Père-Lachaise and Mt. Auburn, Laurel Hill rested in a riverside setting on the city’s northwest edge, was devoid of religious affiliation, and provided the dead and their mourners with privacy and tranquility. Privately hired gardeners and landscape architects maintained the grounds while Smith insisted only lot-holders could ride carriages during weekday hours. Laurel Hill increasingly became a major attraction; more than 30,000 people visited in 1846, and by 1860 the annual total reached 140,000.

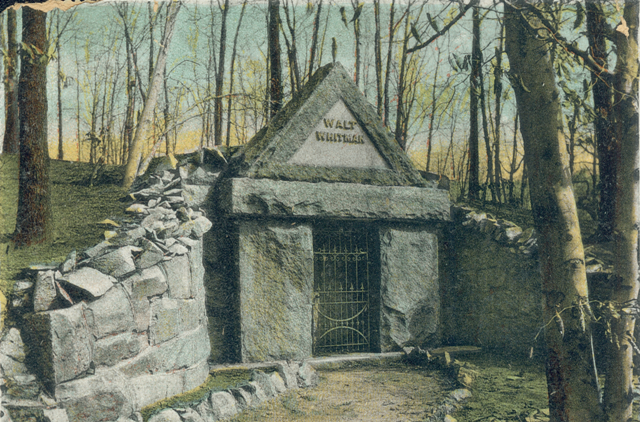

Philadelphia’s other premier rural cemetery, the Woodlands, originated in 1734 as a small burial ground and later was moved to Andrew Hamilton’s gardens on the west bank of the Schuylkill River. New Jersey and Delaware also experienced the rural cemetery trend. Trenton’s Riverview Cemetery and Camden’s Harleigh Cemetery opened in 1858 and 1885, respectively, with the former growing out of a Quaker burial yard from the 1730s. In 1872, the first half of Wilmington’s Riverview Cemetery was dedicated, with landscaping by architect Hermann J. Schwarzmann (1846-1891), who designed many of the buildings for Philadelphia’s 1876 Centennial Exhibition. Smaller towns replicated the rural cemetery in miniature, including grandly arched entrances, mausoleums for the local gentry, and, starting in the 1860s, memorials to the Civil War.

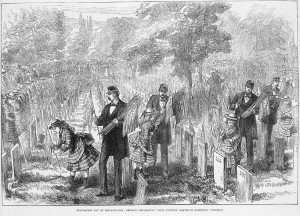

Civil War’s Influence

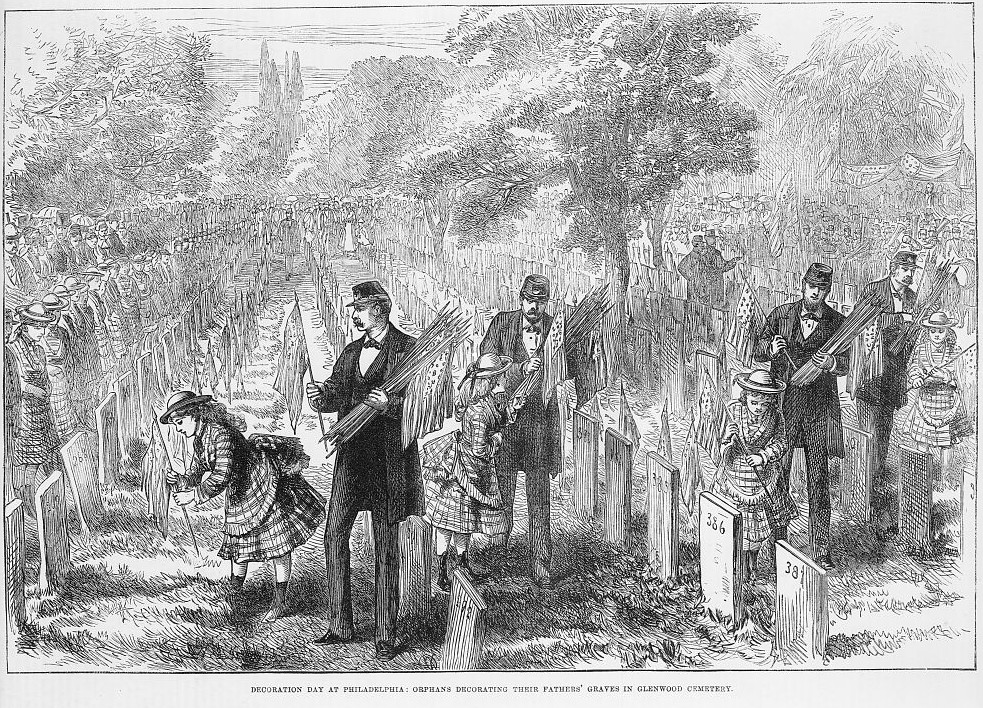

The Civil War produced unprecedented numbers of casualties. During and after the conflict, the need arose to properly memorialize the dead and commemorate battlefield heroism. The result was the creation of national cemeteries, many of which expanded in later decades. These included Mt. Moriah in southwest Philadelphia, which began as a rural cemetery in 1855; Philadelphia National Cemetery, opened in 1862 in the city’s West Oak Lane neighborhood; Beverly National Cemetery in Burlington County, New Jersey, established in 1864; and Finns Point in Salem, New Jersey. While Finns Point was not dedicated until 1875, its first interments included captured Confederate soldiers from Gettysburg.

Following the Civil War, as the region urbanized and increased in population, factories, office buildings, and transit infrastructure obliterated many colonial and antebellum cemeteries. Those that survived often fell prey to neglect or vandalism. Moreover, the process of death became highly professionalized as families adopted cremation practices or hired funeral directors to prepare the deceased and conduct ceremonial rituals. In response, cemeteries increased in size in suburban and rural areas of Greater Philadelphia. Laurel Hill, confined by urban growth, expanded in 1869 to include West Laurel Hill Cemetery on the other side of the Schuylkill River. Wilmington’s Cathedral Cemetery (est. 1876) and Silverbrook Cemetery (est. 1898) appeared on the city’s southwest edge to serve the city’s growing Catholic and Jewish populations. Its Riverview Cemetery expanded in 1916 when the Wilmington Free Library acquired the Presbyterian Church’s grounds for a new building. In 1902, Eden Cemetery opened in Collingdale, Delaware County, becoming the area’s first Black cemetery outside the Philadelphia city limits.

After the turn of the twentieth century, memorial parks heralded a new age of cemetery design. With Los Angeles’ Forest Lawn Memorial Park (est. 1917) as inspiration, cemeteries such as Lakeview (est. 1924) in Cinnaminson, New Jersey, anticipated the patterns of suburbanization that drastically transformed the region. After World War II and with increasing automobile use and suburban sprawl, grounds such as Memorial Park (est. 1954) in Woodbury, New Jersey; Wilmington’s All Saints (1958); and S.S. Peter and Paul (1958) in Springfield, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, mirrored the flight of families, commerce, and institutions from urban centers. Concurrently, many older cemeteries, including Mt. Moriah, Old Camden, and Greenwood/Knights of Pythias in the Frankford section of Philadelphia, suffered from abandonment and vandalism.

Cemeteries also were relocated or removed for urban development projects. In 1953, Temple University acquired the 114-year-old Monument Cemetery. Needing the fifteen-acre parcel for additional parking, Temple requested the site be condemned and, in 1954, more than 20,000 graves, many in wooden coffins, were reinterred in Fox Chase’s Lawnview Memorial Park. In the early 2000s, campaigns sought to save Mt. Moriah and Greenwood. While in 2005 Mt. Moriah was deemed endangered by the Preservation Alliance of Greater Philadelphia, new ownership assumed responsibility for Greenwood and in 2012 spent more than $1 million removing garbage and discarded appliances from the grounds.

Despite periods of geographic expansion, advances in technology, ethnic and religious diversity, and the repurposing of urban spaces, greater Philadelphia’s extinct and surviving cemeteries illustrate the metropolitan area’s centuries of social and economic development.

Stephen Nepa is an urban-environmental historian. He is contributing author to A Greene Country Town (Penn State University Press, due 2015) and The Women of James Bond (Columbia Univ. Press, due 2015), and has written for Environmental History, Buildings and Landscapes, New York History, and other publications. He received his M.A. from the University of Nevada and his Ph.D. from Temple University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2014, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- First-ever tour takes visitors through historic cemeteries in Germantown (WHYY, October 13, 2014)

- An epic effort to breathe new life into once abandoned Philly cemetery (WHYY, April 15, 2016)

- In Philadelphia, finding dignity for bodies left unclaimed (WHYY, June 1, 2016)

- Historic cemeteries struggle to return from decades of neglect (WHYY, November 15, 2016)

- In South Jersey, a familiar fight to save a historic African-American cemetery (WHYY, April 26, 2017)

Links

- Historic Philadelphia Burial Grounds Map (Philadelphia Archaeological Forum)

- Gloria Dei Old Swedes' Episcopal Church

- The Woodlands Cemetery

- Mikveh Israel Cemetery (PhilaPlace.org)

- Christ Church in Philadelphia

- Friends of Mount Moriah Cemetery

- Kahal Kadosh Mikveh Israel (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Philadelphia National Cemetery (National Park Service)

- Harleigh Cemetery

- Renovation of playground Over Cemetery is Halted (Philly.com)

- Friends of Laurel Hill Cemetery

- Laurel Hill Cemetery Is more than a Final Resting Place (PhilaPlace.org)