Cricket

Essay

The rise, fall, and rebirth of the sport of cricket in the Philadelphia region reflected political, social, and economic change. Cricket once flourished in the city, which produced some legendary players known throughout the cricketing world. The rise of other leisure activities supplanted the game, however, until a moderate resurgence in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

Cricket came to Philadelphia from Great Britain, where its roots in the English countryside extended as far back as the late 1500s. Cricket clubs grew and competition between “county” teams expanded with increased financial interest in the sport after the restoration of the English monarchy in 1660. For much of its history, cricket both reached across and reflected the deep class divisions in British society. Despite its genteel image, cricket was never a sport played solely by the upper class. Many of the world’s greatest cricketers rose from working-class origins; it was once said that “when England needed a fast bowler, all it had to do was whistle down a Nottinghamshire coal mine.” Incredibly, it was not until the early 1960s that England stopped dividing its first-class cricketers into two classes: independently wealthy “gentlemen” amateurs and middle and working-class “players” who were paid for their services. For the “gentlemen,” participation in cricket embodied many of the qualities and characteristics desired by the upper crust of English society—friendliness, gentlemanly competition, integrity, and hospitality.

American colonists seeking access to the upper echelon of British society closely followed the customs of the home country, including reports of British cricket matches published in colonial newspapers in the 1750s. When Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) traveled from Philadelphia to London in 1760 for the coronation of King George III (1738-1820), he returned with a copy of the 1755 Laws of Cricket published in London by the famous Marylebone Cricket Club, further spreading the game throughout the region. During the American Revolution, many journals of Continental soldiers—including those stationed at Valley Forge in the winter of 1777-78—noted that George Washington (1732-99) often played “wickets” with his troops. Cricket also became the first intercollegiate sport in the United States, played at Dartmouth College as early as 1793 and locally starting in 1833 by Haverford College, which soon competed with other local colleges and universities.

Rapid Growth in 1830s

Cricket expanded throughout the United States in the nineteenth century and grew rapidly in the Philadelphia region in the 1830s, aided by the arrival of British immigrants. Philadelphia developed into an epicenter of the sport. The Union Cricket Club, established in 1843, consisted of English-born working-class weavers from Germantown’s Wakefield Mills and mechanics from the suburb of Kensington. The Union Club’s upset defeat of New York’s St. George’s Cricket Club not only put Philadelphia on the cricket map, but also captured the imagination of many native Philadelphians. The first international athletic competition—predating the modern Olympic games by nearly fifty years—took place in New York in 1844 when teams from the United States and Canada faced off in a cricket match.

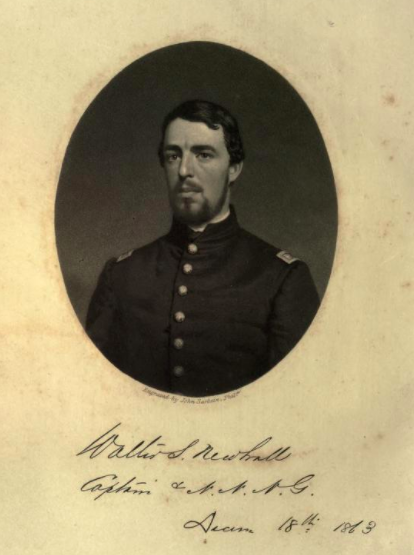

By 1860, New York and Philadelphia alone had more than six thousand cricket players. A book published in the memory of prominent Philadelphia cricketer Walter S. Newhall (1841-64), who died while serving with the Third Pennsylvania Cavalry in American Civil War, noted that within the city “cricket became the fashion, the great excitement and chief topic of a large class, for six months of the year. Everybody soon belonged to one club or another.” This growing obsession with the sport put into place an organization of teams that produced a pipeline of cricketing talent that lasted until the early 1900s.

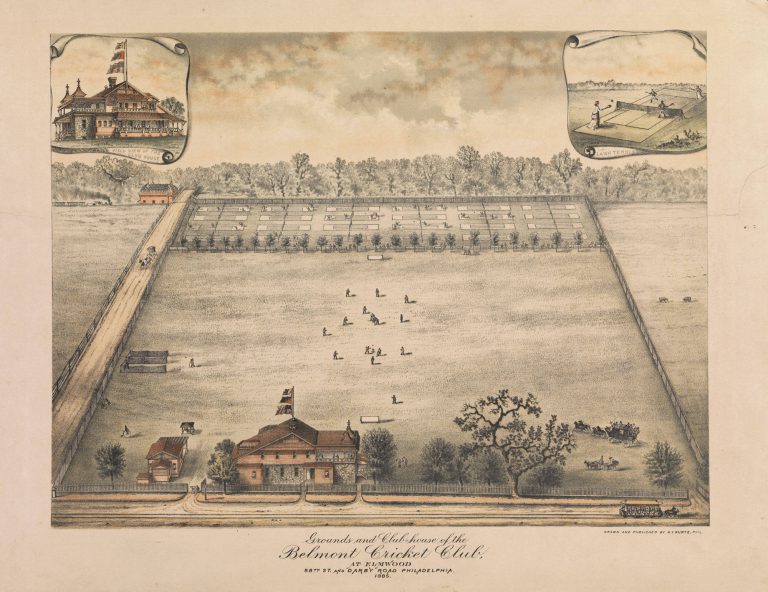

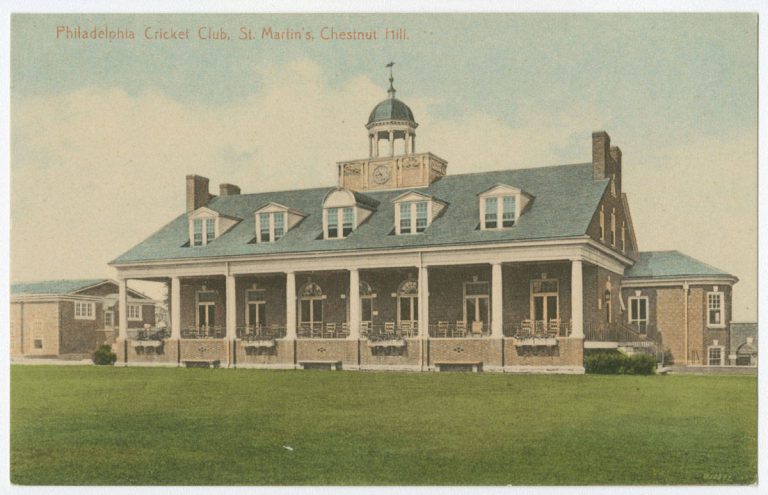

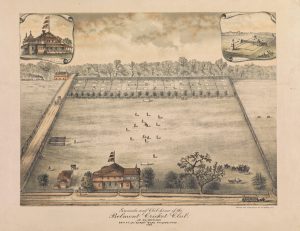

While English-born factory workers made up some of the Philadelphia region’s first cricketers, young men of notable families–seeking athletic competition while also emulating the upper crust of British society—also became converts to the sport. One such Philadelphian was William Rotch Wister (1827-1911), born in Germantown in 1827. While a student at the University of Pennsylvania, Wister founded the “Junior Cricket Club,” one of the first cricket clubs in the country for Americans. While the “Junior Club” was short-lived, its match against Haverford College on May 7, 1843, was the first intercollegiate sporting event in Penn’s history. Known as the “Father of American Cricket,” Wister went on to play a role in the 1854 founding of the Philadelphia Cricket Club and Germantown Cricket Club, which eventually produced some the country’s most notable athletes. The “big four” clubs—Philadelphia, Germantown, Merion (founded in 1865) and Belmont (founded in 1874) also attracted some of the most prominent families in the Philadelphia social register, including Whartons, Biddles, Cadwaladers, and Fishers, and others notable in the history of Philadelphia and its many civic institutions.

Hosting Teams From Around the World

Cricket continued to flourish in Philadelphia in the decades after the Civil War, despite the growing popularity of baseball. Beginning in 1878, the big four clubs combined to field the “Gentlemen of Philadelphia” sides, amateurs who represented Philadelphia in the highest levels of international first-class cricket competition until the First World War. The Philadelphians not only hosted and competed against the best teams and players from around the world, they did so with the support of crowds of several thousand that regularly attended these matches. These spectators represented a cross section of Philadelphia society that, according to a contemporary account, ranged from “millionaires, coaching parties, and box holders to newsboys.”

Many of the homegrown players from this “golden age” of Philadelphia cricket ranked among the game’s best. John B. Thayer Jr. (1862-1912) attended the University of Pennsylvania and made his debut for the Merion Cricket Club at the age of fourteen. He traveled to England in 1884 and competed in seven first-class international cricket matches between 1879 and 1886. After his first-class cricketing career ended, Thayer married into a prominent Philadelphia family and rose to the position of vice president of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Returning from a family trip to Europe in April 1912, Thayer booked his passage on the ill-fated maiden voyage of The Titanic. While his son John “Jack” Thayer III (1894-1945) survived, the elder Thayer perished in the disaster, his body never recovered. George Patterson (1868-1943), who played with Haverford College, the University of Pennsylvania, and the Germantown Cricket Club, made his debut in first-class cricket at the age of sixteen. Patterson traveled to England with the Gentlemen of Philadelphia team in 1889 and as captain of the team in 1897. His single innings batting total of 271 runs still stands as the nineteenth-century North American record.

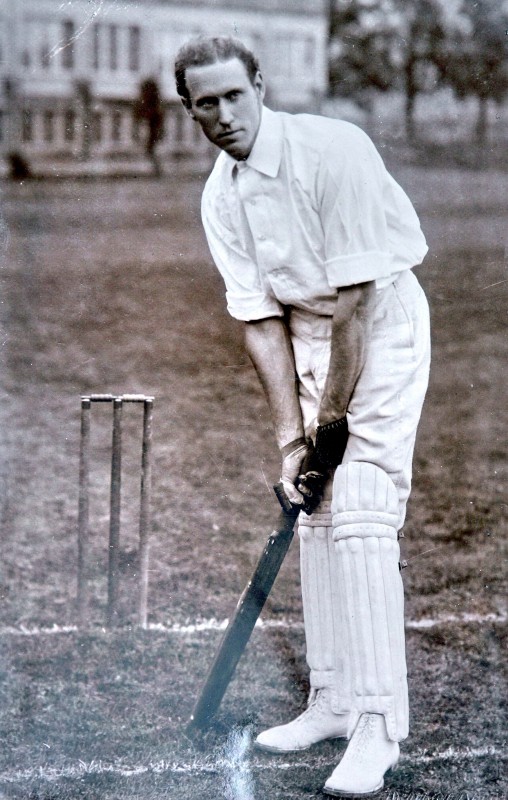

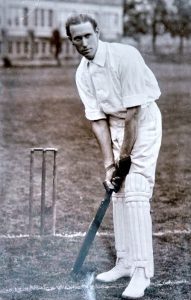

The Philadelphians’ 1897 tour of England was most notable for the performance of another homegrown Philadelphian, considered by many as the greatest cricketer ever to emerge from the United States. John Barton “Bart” King (1873-1965) ranked so highly in the echelons of the sport that his death was noted on the front page of the London Times. King did not fit the mold of the young athletes attracted to the sport. His background was middle class—his family worked in the linen business—and his first sport was baseball. Picking up cricket at the age of fifteen, he had great success as a batsman. He became the first American batsman to score a triple century—315 runs—in 1905 and a staggering tally of 344 the following year, which remained the North American record in 2016. Due to his tall, lanky physique, King also became a bowler (the equivalent of a baseball pitcher) and a legendary career began to take shape. In a performance against one of the top county teams in England in 1897, King dominated in both batting and bowling, leading his team to a surprising victory. King had plentiful, financially lucrative opportunities to play county cricket in England after the tour, but he decided to return to Philadelphia and his beloved Belmont Cricket Club. Plum Warner (1872-1963), the “Grand Old Man” of English cricket, noted on King’s passing in 1965 that, “had he been an Englishman or an Australian, he would have been even more famous than he was.”

Baseball Ascends

By the early 1870s, even as cricket was beginning its golden age in Philadelphia, the forces that would lead to its demise as a popular spectator sport were well underway. Baseball, which had gained popularity among soldiers during the American Civil War, was rapidly spreading across the country. It was easier to set up, had simpler rules, and did not need a perfectly rolled and manicured pitch suitable for match play. As the United States progressed into the economic growth of the Gilded Age, professional baseball teams became one of the many avenues in which entrepreneurial business minds sought to make their fortunes. Unlike the still genteel world of cricket, which frowned upon “players” being paid, owners of baseball teams happily paid their players, who drew larger and larger crowds. This birth of modern professional sports in the United States, which started with baseball and soon added football, basketball, and hockey, eroded much of the interest and support in cricket.

The “cricket” clubs also changed. Their wealthy members, less interested in the rituals of British society, became more absorbed in golf and tennis, and many cricket grounds began to disappear underneath tennis courts and golf courses. Philadelphia and Germantown stopped hosting cricket completely by the 1920s. The Belmont Cricket Club folded in 1914, its grounds becoming the Kingsessing Recreation Center. The onset of World War I in 1914 also eliminated potential international competition for the few American cricket clubs that remained.

By the first decades of the twenty-first century, a new generation of immigrants from South Asian countries played a role in the sport’s revival. Their interest sustained a twenty-team league competing all over the Philadelphia region. Haverford College, whose library holds many of the treasures from American cricket’s golden age, remained the home of a varsity cricket team, and Philadelphia continued to host the largest international cricket festivals in the country every May. Cricket matches in Philadelphia did not draw thousands of spectators, and homegrown Philadelphia cricketers did not rank among the world’s best. Yet even in a city with considerable passion towards major professional and college sports, cricket did not totally disappear.

Michael Karpyn teaches History, Economics, and Advanced Placement U.S. Government and Politics at Marple Newtown Senior High School in Newtown Square, Pennsylvania. He has served as a Summer Teaching Fellow at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, where he is a member of the Teacher Advisory Group. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History