Crime

By Eric C. Schneider | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

Crime is inextricably linked to Philadelphia’s shifting economic fortunes. Its history reflects the region’s status as a port and point of entry for goods, immigrants, and migrants, where concentrations of both wealth and poverty developed in a center of American commerce and industry. As a type of economic activity, forms of crime changed dramatically as the Philadelphia region transformed from a preindustrial, to industrial, to post-industrial metropolis.

Philadelphia, as a seaport and the largest city in the North American colonies, hosted seamen, laborers, runaway servants, and transients, the footloose men most likely to be involved in crime and to patronize the vice trades. Taverns, brothels, and gambling dens dotted the walking city that relied on night watchmen to look out for fire more than public safety. In the absence of what would be recognized as a police force, thieves pilfered purses from the unwary and burgled goods from warehouses and docks, and feared only the “hue and cry” that might lead a posse of pursuers to stop and beat them. Those caught and brought to trial faced a penal code that had eliminated English practices of whipping, branding, cropping body parts, and hanging for most crimes, but Pennsylvania’s penal code reverted to these punishments in 1718, and they remained in effect until the adoption of a new state constitution after the Revolution in a largely futile attempt to stem crime and disorder.

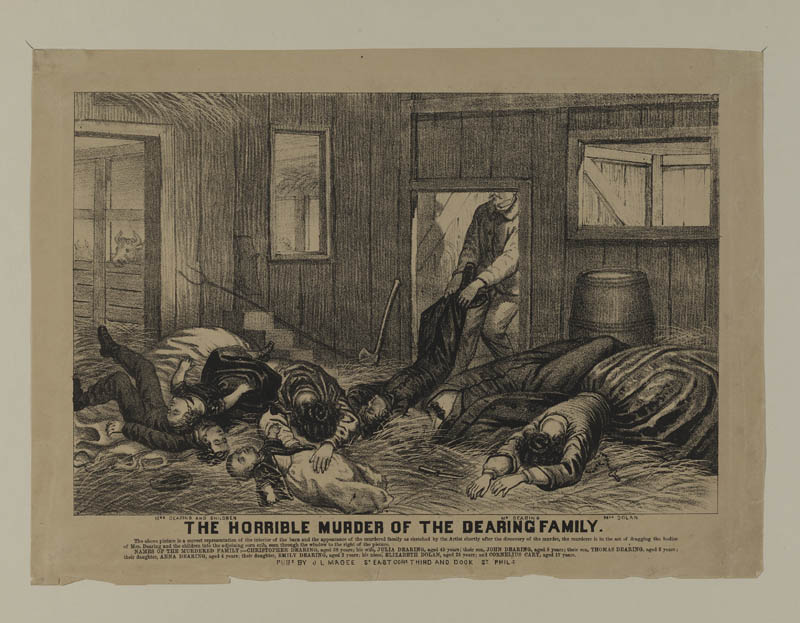

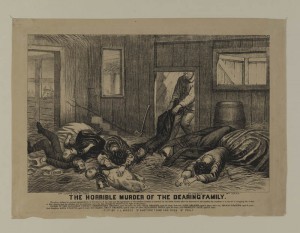

Violence (as reflected in indictments for murder, the most reliably counted form of crime) remained rare in Philadelphia until the middle of the eighteenth century. When people killed, they murdered intimates—neighbors and friends—a pattern that holds true into the present. Men killed women amid allegations of infidelity or in response to challenges to patriarchal authority. Irritations with friends or neighbors sometimes took a violent turn, especially when fueled by drink, and an unlucky thrust with a knife or baling hook might send one man to the grave, the other to the gallows. Masters killed their servants or apprentices as murder extended downward in the social order, but rarely the reverse. Men committed about 90 percent of murders, in a pattern that characterizes modern societies as well.

Among women, infanticide was the most common form of homicide as women had few ways to terminate unwanted pregnancies. Charges were rare, but those charged faced significant legal hurdles. Unlike those accused of murder, who were presumed innocent until proven otherwise, women charged with infanticide faced the presumption that an infant was born alive and a defense of stillbirth had to be supported by at least one witness. Nonetheless, few women were convicted as juries were loathe to find desperate young women guilty.

Violence increased in Philadelphia in the decade or so before the American Revolution, before subsiding again in the last decades of the eighteenth century. Loss of faith in the king, a government unwilling to redress grievances, sharp fractures in the ruling elite, and an increasingly diverse society disrupted the political and social hierarchy that had tamped down violence. Murder climbed steadily—indictments for murder more than doubled from 3 per 100,000 during the 1750s to 7 per 100,000 in the 1760s—and remained high in the Revolutionary era. While some acts were clearly political attacks on supposed loyalists or Tories, most followed the usual pattern of neighborhood and family strife. Criminal justice proceedings were temporarily disrupted during the Revolution, and it is likely that the pervasive political violence loosened normal constraints on behavior.

Poverty and Crime

A pattern of declining murder rates during periods of political consensus and faith in government (and rising rates when these conditions changed) appeared early in the nation’s history. The fellow-feeling engendered by the formation of a new, more democratic government, a revised criminal code that limited corporal punishments, and the ratification of the Constitution sent murder rates plunging in post-Revolutionary Philadelphia, with fewer than 1 indictment per 100,000 in the 1780s and 1790s. However, rising inequality in the city meant other forms of crime persisted: The combination of wealthy travelers and a countryside in which to hide provided an ideal combination for robbery, which plagued the country roads near Philadelphia, while growing affluence provided an incentive for larceny and burglary.

African Americans and Irish-born immigrants each comprised about a third of those charged with crime in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The overrepresentation of Black and Irish people indicated both prejudice—the expectation that these groups would fill the jail and the poorhouse—as well as the activities of very poor people. The most common crimes, the theft of clothing, food, or household items pilfered by servants, were clearly the acts of individuals scrabbling for survival.

In the early nineteenth century, the invention of new technologies, especially the power loom that mechanized the work of artisans in Britain, forced households into poverty and sent streams of immigrants across the ocean to Philadelphia, where they faced ruinous competition and neighborhood strife. In the 1830s and 1840s battles between Irish Catholics and Protestant Orangemen, immigrants and nativists, workers and employers, or between rival volunteer fire companies, saw buildings and churches set ablaze while streets reverberated with the sounds of musketry and even cannon fire. Only poor marksmanship and unfamiliarity with weapons kept casualties low. The Philadelphia sheriff called on citizen posses to suppress disorder, but on a number of occasions only the militia managed to restore peace to the city.

Gangs such as the Rats, the Killers, and the Flayers reigned in Moyamensing and Southwark, just across South Street and outside of Philadelphia’s borders. While these gangs included petty criminals, their principal goals were more social than economic. Gang members supported volunteer fire companies, supplying the manpower to pull engines through the streets and to battle rival companies for access to water supplies. On election day, gangs provided strong-arm support for getting out the vote or preventing others from voting, services that gained them income and some immunity from criminal prosecution. And on a day-to-day basis, they patrolled neighborhood boundaries against outsiders, particularly African Americans. In the five major race riots that occurred between 1829 and 1849, gangs led white rioters in attacking African Americans and looting and burning Black residences.

Some long-lived gangs, such as the Schuylkill Rangers (c. 25 years), drawn from an Irish immigrant community on the banks of the Schuylkill River, began by resisting nativist and anti-Catholic attackers, but evolved into a more organized form of criminality. They became river pirates, demanding a tax from barges heading to the city, robbing the trade carried across the river at nearby Gray’s Ferry, and raiding wharfs and warehouses.

Responding to Crime

Philadelphians responded by organizing new mechanisms of social control. Eastern State Penitentiary (1829), the nation’s first, loomed ominously above the city as a warning that miscreants could count on years of solitary confinement. Patrolmen and inspectors were added to the constables and night watch (1833), although criminals could still escape arrest by crossing a street to another township. The consolidation of Philadelphia’s political boundaries, the expansion of the police, and charter reform (all in 1854) replaced the different township jurisdictions and the ineffectual committee structures dependent on citizen volunteers. Finally, centralized control (1855) over fire companies (and professionalization in 1871) eliminated the disorder involved in firefighting.

Better policing and new institutions found their match, however, in more organized crime. Burglars raided shops and warehouses with sets of skeleton keys designed to pick different types of locks and then disposed of their booty to fences, who specialized in specific types of goods. Safecrackers had a variety of drills for iron and eventually steel-plated safes. Counterfeiters and forgers enjoyed the most lucrative returns in an age of international trade and no exclusive national currency, copying different states’ bank notes and merchants’ letters of credit, while con men advertised in newspapers to sell counterfeit currency to gullible businessmen, who received a package of green cut paper (hence the “green goods swindle”) instead. Gamblers introduced English bookmaking and assumed control over betting on (and fixing) sports. Meanwhile, corrupt police detectives developed a scheme of recovering stolen goods and then splitting a reward from their owner with a cooperating thief.

Despite riots and disorder, homicides remained relatively rare in the city until the 1850s. The collapse of political consensus over westward expansion and slavery and continued ethnic tensions drove murders upward, while the introduction of Samuel Colt’s concealable revolver made murder easier than before. Indictments for murder in 1853-59 climbed to 4 per 100,000, the highest rate since the founding of the nation. Revolvers continued to proliferate after the Civil War, and the proportion of homicides committed with handguns increased. Overall, however, homicide indictments declined in the late nineteenth century, staying below 3 per 100,000 in the 1880s and 1890s even as depressions and labor strife disrupted society.

The decline in homicide does not reflect the large number of infant killings each year for which no one was ever charged. Between 1861 and 1901 an average of 55 infants were found dead outdoors or drowned in outhouses each year, while physicians and public authorities estimated several hundred more died of neglect or abuse, but with no definitive sign of foul play. Single mothers seeking to hide a birth and parents unable to manage another child resorted to infanticide, abandonment, and depositing newborns at “baby farms,” where death rates were high but intent to kill impossible to prove.

The Vice Trade

Prostitution remained an important source of employment for women whose wages as seamstresses, waitresses, domestics, and even department store clerks were rarely enough to support them. While some women had “friends” who helped support them, others relied exclusively on prostitution. Vice districts were a lucrative and well-advertised component of the city’s mainstream economy and employed many hundreds of women. By the 1890s, two sizable vice districts had emerged to bracket Philadelphia’s downtown, one along South Street, the other north of Market Street, between Ninth and Eleventh Streets.

The area north of Market, known as the “tenderloin,” was the city’s primary entertainment district with cabarets, theaters, dance halls, and opium dens. White, native-born women served an upper-class clientele of businessmen and revelers from the entertainment spots nearby who used published visitors’ guides that evaluated the quality of sex services. There were an estimated 300 brothels in the tenderloin in addition to houses of assignation (where women could take the men they met on the street or in a dance hall), as landlords broke up the large houses in the neighborhood into single rooms that catered to transients—and their guests.

Brothels operated openly by bribing the police, who in turn paid off the ward leaders responsible for their appointment to the force. Despite occasional clean-up efforts, Philadelphia’s tenderloin only came under sustained enforcement pressure during World War I, when prostitution was outlawed within a five-mile radius of a military training camp, and municipal authorities across the nation were pressed to close down open vice districts. Some commercial sex migrated to Market Street, where women trolled for soldiers and sailors on the street. Since Market Street hosted movie theaters, restaurants, and most of the city’s department stores, it was a less sexualized commercial zone than the tenderloin, and streetwalkers blended more easily into the flow of pedestrians.

The city’s second vice district ran along South Street and coincided with the major area of African American settlement, to the consternation of W.E.B. Du Bois, who in The Philadelphia Negro (1899) deplored its demoralizing association with the neighborhood. African American prostitutes catered to the transient merchant seamen and dockworkers from the nearby commercial wharves. In Philadelphia’s Black population, women outnumbered men—the reverse of the immigrant white communities that supplied their customers. Enforcement pressures were fewer than in the tenderloin, since the area was less obviously a commercial center, and because white reformers, unlike Du Bois, were indifferent to the presence of vice in a Black neighborhood.

The most obvious social cost of coexisting with the vice trade was the violence associated with it. The homicide rate among African Americans ranged from 6.4 indictments per 100,000 in the 1860s to 11.4 in the 1890s, about five times the city rate. Illegal entrepreneurs required some means of protection, since they could not rely on police, but also the history of white attacks on African Americans may have been an incentive for young men to carry weapons. As a result, the commonplace disagreements that whites settled with fists and clubs took on a more deadly tone among armed African Americans.

Crime as Big Business

The same technologies that supported business, real estate, and industrial development in the city and surrounding region, and allowed the rapid transmission of information, also meant that professional criminals could better organize their trade. Railroads and intercity streetcar service spread settlement into the Main Line and beyond, as wealthy Philadelphians escaped the tenements and factories that crowded the city. They found to their dismay that, while other crimes were rare, rings of professional burglars followed the money. Con men could employ a dozen or more individuals working fake wire services and purporting to share tips on stock transactions. And prostitutes moved from city to city as part of a circuit similar to the ones followed by entertainers and vaudeville performers. But it was Prohibition that really turned organized crime into big business.

The scope of illegal enterprise changed with the managerial tasks of making, importing, and distributing illegal liquor. In Philadelphia and South Jersey, Jews (with Italians as secondary partners) dominated the bootlegging trade and vertically integrated their industry from supply to retail while forging alliances with other gangsters both nationally and internationally. Oceangoing vessels brought Canadian whiskey into Atlantic City from where it was distributed up and down the East Coast, and beer from South Jersey breweries quenched thirsts throughout the mid-Atlantic region. These same international trade routes and associations formed the basis for the eventual importation and distribution of heroin.

The partnership between Jews and Italians continued well after the end of Prohibition. When Tennessee Senator Estes Kefauver brought his investigatory committee to Philadelphia in 1950-51, he found the familiar pattern of gambling, loan-sharking, labor racketeering, and police payoffs. Kefauver’s committee focused on Jewish organized crime, but the aging gangsters dragged reluctantly before the television cameras were well on their way to retirement, prison, or death. It was Angelo Bruno (1910-80), the “Quiet Don,” who would become the face of a new generation of mobsters.

Not the first Mafia don in Philadelphia but perhaps the most significant, Bruno became the head of the Philadelphia-South Jersey mob in 1959 and managed the ascent of Italian-dominated organized crime. Under Bruno, loan-sharking and gambling remained central money-making enterprises, and the opening of casino gambling in Atlantic City in the late 1970s offered additional revenue through mob control of key construction and hotel services unions. However, Philadelphia’s Mafia quickly burned itself out. Battles over Atlantic City revenue and impatience with Bruno’s conservative leadership led to his assassination in 1980. Chaos followed as murderous, but largely incompetent, mob bosses left a trail of bodies, with lengthy prison terms for the survivors.

Internecine warfare among Italian mobsters provided openings for others. The Black Mafia, organized by former members of the Twentieth and Carpenter Street Gang, began by extorting criminals in its South Philadelphia neighborhood. By the early 1970s, the group had expanded into heroin dealing throughout the city, with connections to New York importer Frank “Black Caesar” Matthews, and eventually became the extortion wing of the Nation of Islam’s Mosque 12. Younger gangsters formed the Junior Black Mafia, and gangs with roots in Jamaica opened new drug-importing routes, while Asian and Russian groups followed the time-honored tradition of extorting and robbing their fellow immigrants.

Murder in the Twentieth-Century City

The homicide rate remained relatively low in the middle decades of the twentieth century. During the Great Depression everyone shared in a common misery and hoped that Franklin Roosevelt would save American capitalism, while during World War II, the populace united behind the war effort and the military absorbed the young men most likely to commit murder (and other crime). The homicide rate spiked immediately after the war, as war-damaged young men returned home, but the increase was only temporary. A strong economy, spurred by Cold War-related defense spending and government subsidies for the new, predominantly white suburbs, meant high wages while an increase in marriage and family formation kept young men from street corners and taverns. Homicide among whites hovered around 2 per 100,000 in Philadelphia into the early 1960s. Other forms of crime (excluding the prostitution, gambling, and loan-sharking promoted by organized crime) also remained fairly low during this period.

With the crime rate low during and after World War II, authorities took aim at juvenile delinquency. During the war, the presence of zoot-suit- wearing boys and girls cruising for soldiers signaled the emergence of a new youth culture focused on consumption and urban pleasures, and seemingly beyond the control of parents. With fathers at war and mothers at work, teenage rebellion might have been a troubling but passing phenomenon, but peacetime did not allay these fears. If anything, new forms of music and cultural styles suggested that juvenile delinquency could not be quarantined in the city and might emerge in the suburbs as well. In this image from 1948, two members of the Juvenile Aid Bureau wake a teen sleeping in a subway station. (Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries)

African Americans, for all intents and purposes, lived in a different city. The homicide rate for African Americans in the early 1950s was 22.5 per 100,000. African Americans from the South flooded into a city that was more segregated than at any point in the past, and migrants brought with them a well-founded mistrust of police and criminal justice. People hustled to make up for inadequate incomes and high city prices, and these activities, without the police protection provided to white organized crime, exposed African American illegal entrepreneurs to the predation of stick-up men. As in the nineteenth century, African Americans venturing into public spaces carried weapons for self-protection, and murders among acquaintances were the most common form of homicide.

The worlds of white and Black Philadelphia slowly converged during the late 1960s, as a collapsing economy and growing heroin use destroyed working-class neighborhoods. Heroin users fueled a dramatic increase in burglary, larceny, and robbery, which largely unskilled and uneducated young men used to support their habits. White flight, already apparent in the 1950s in response to African American migration and the lure of the suburbs, accelerated in the 1960s as the crime rate rose and abandoned factories drained the value out of nearby row houses. Philadelphia’s homicide rate increased by 300 percent between 1965 and 1974, the same decade the city lost about 40 percent of its industrial jobs. Racial tension, job loss, and increased gun ownership resulted in frayed personal relations and a spiraling homicide rate. As in previous decades, these tensions were internalized: Black people murdered Black people and whites murdered whites with most victims the closest at hand—friends and family.

These trends were not limited to Philadelphia. In nearby Camden, New York Shipbuilding, Campbell Soup, and RCA all closed or decamped for locales with cheaper, nonunionized labor, and the city lost about half of its industrial base between 1960 and 1970. Corporate board decisions to gut Camden’s economy trapped African Americans in place, while those whites who were able moved to burgeoning suburban Camden County. The change in the homicide rate was startling; a modest 3.4 homicides per 100,000 in 1960 became 26.3 in 1970 and 31.9 in 1980 as the underground economy replaced the world of legitimate work.

The Underground Economy

With a virtual collapse of the job market for unskilled labor, the underground economy became the only economy in sections of Philadelphia, Camden, and Chester. Shifts in the drug trade meant the Philadelphia region had some of the purest heroin and least expensive cocaine in the nation. The arrival of crack cocaine during the 1980s and disputes over drug-selling turf settled with increasingly powerful semiautomatic weapons sent murder to new heights. Camden (an average of 50.3 homicides per 100,000) and Chester (an average of 51.3) had among the nation’s highest homicide rates during most of the 2000s, and Philadelphia started the new century as the city with the highest homicide rate (22.5 per 100,000) among the nation’s ten largest cities. Not only do the poorest cities have the highest homicide rates, but the poorest neighborhoods within these cities concentrate the effects of poverty and the violence associated with the underground economy.

Since its founding, Philadelphia has been a source for illegal, but highly desirable, goods and services for the region. Their provision rested on the exploitation of the poor—women who worked as prostitutes, and men who organized gambling and sold illegal liquor and drugs to wealthier consumers. However, for most of the region’s history, trends in murder moved along a separate trajectory from trends in vice, other crime, and disorder. In the late twentieth century, these trends merged as the underground economy became more central to the economic fortunes of the inner city, the inner city itself became more isolated from the mainstream economy, and new, high-powered weapons proliferated. One thing is clear from this history: The evolution of crime and violence has paralleled developments in the urban economy over three centuries, and solving these problems depends on a larger resurrection of urban economic fortunes.

Eric C. Schneider, a historian at the University of Pennsylvania, has written three books on American urban history and is currently working on a history of murder in Philadelphia since 1940. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2014, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- Juvenile Delinquency Philadlephia, Pa Hearings Transcript, April 1954 (Archive.org)

- When Columbia Avenue Erupted (Hidden City Philadelphia, August 27, 2014)

- Crime Maps and Statistics (Philadelphia Police Department)

- Mapping Vice in Early Twentieth-Century Philadelphia (The Spacial History Project at Stanford University)