Girard’s Bequest

Essay

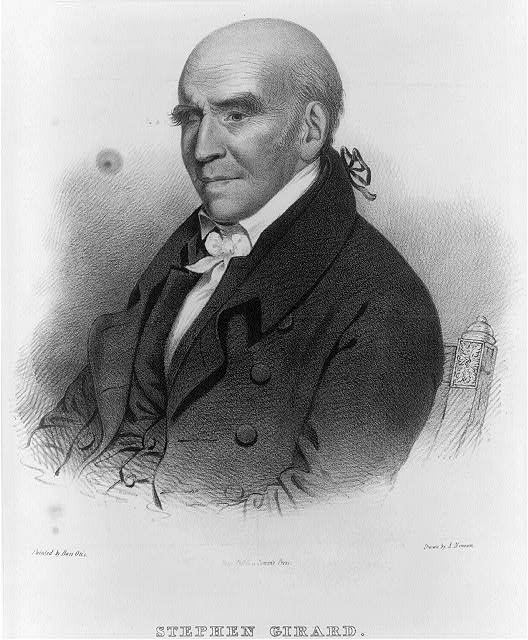

On December 26, 1831, the richest man in the United States died and gave the city of Philadelphia the great majority of his fortune. Committed to philanthropy for much of his life, Stephen Girard (1750-1831) had wealth at the time of his death estimated at more than $6 million, earned during his life as a merchant and banker, from his investment in internal improvements like the Schuylkill Navigation Company, and in real estate in Philadelphia and beyond. Having no biological children as heirs, Girard left some of his fortune to his extended family. However, with the majority of his estate Girard invested in Philadelphia’s physical infrastructure with the intention of making it cleaner and healthier and in the city’s most impoverished citizens with the intention of making them more productive members of society.

Drafted with the help of attorney William J. Duane (1780-1865), the twenty-six sections of Girard’s will covered thirty-five pages, plus a page-and-a-half codicil. Right away, Girard made clear his commitment to philanthropy. He dedicated the first eight sections of the will to established institutions in Philadelphia, like Pennsylvania Hospital, as well as those he intended to establish, like a school in Passyunk Township. Among other charitable bequests, he set aside money to be held in trust to provide fuel to help keep Philadelphia’s struggling citizens warm in the winter.

The middle part of the will set aside notably smaller bequests to Girard’s extended family and individuals who served in his household, but then its final sections meticulously explained how the bulk of Girard’s immense estate should be handled. Much of the money for these more substantial bequests derived from Girard’s extensive real estate holdings. For instance, the will stipulated that Girard’s property in Louisiana was to be held in trust jointly by the Corporation of the City of New Orleans and the mayor, alderman, and citizens of Philadelphia, and his real estate in Kentucky was to be sold, the proceeds to be used to accomplish Girard’s philanthropic goals.

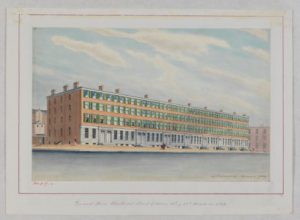

The most notable section of Girard’s bequest provided funds for the “Orphan Establishment” that became Girard College. With two million dollars, the largest single sum bequeathed in the will, Girard instructed the city to establish a school for “poor white male orphans.” The will explained precisely how and where each building should be constructed, detailing dimensions and materials. Construction of the College began in 1833 and the school admitted its first students in 1848. To accomplish his other main goal—making a cleaner and healthier city—Girard dedicated $500,000 to improve the area of the city along the Delaware River, resulting in the construction of Delaware Avenue.

Girard also foresaw the practical and legal challenges that his bequest would create. For the city to effectively inherit his fortune, it would need to establish committees and accounts to manage and safeguard his investments, and for that the city would need the help of the state. To ensure cooperation, Girard bequeathed $300,000 to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania for internal improvements (intended for canals), but only to be paid after laws were passed to implement the other improvements for Philadelphia. In so doing, Girard created an extra incentive for the state and the city to cooperate.

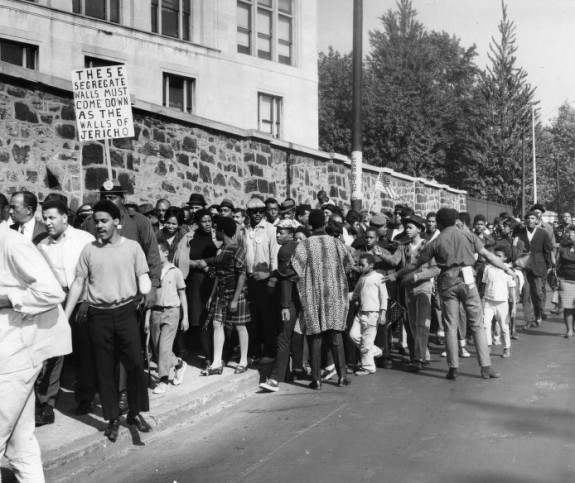

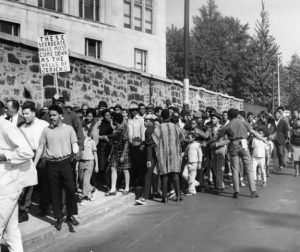

Such cooperation was easier planned than accomplished. Girard’s bequest required the coordination of authorities at city, state, and national levels. This was no easy task and debates over how to manage the estate consumed significant time and energy within Philadelphia’s city government throughout the mid-nineteenth century. Additionally, the comparatively smaller bequests set aside for family members left Girard’s extended family feeling snubbed. Their challenges to the will made it to the Supreme Court of the United States. Justice Joseph Story (1779-1845) wrote the opinion in the case Vidal et. al v. Mayor, Alderman, and Citizens of Philadelphia (1844) that upheld the will and set new precedent for trust and corporate law. With this decision, Justice Story cemented the right of corporations not only to inherit real and personal estate, but also hold it in trust just as a citizen could. Girard’s will reached the Supreme Court again in the twentieth century in the aftermath of Brown v. Board of Education (1954), this time challenging the stipulation that Girard College admit only white boys. In the case Pennsylvania, et al. v. Board of Directors of City Trusts of the City of Philadelphia (1957), the Trustees of Girard College argued that the will was inviolable, but this time the Court disagreed. Girard College was eventually desegregated in 1968; the first female students enrolled in 1984.

After large expenditures for the construction of Girard College and Delaware Avenue, the value of the Girard Estate grew throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, deriving income largely from investments in coal lands in Schuylkill County. Managed by Philadelphia’s Board of Directors of City Trusts, established in 1869, in the twenty-first century the Girard Estate continued to derive assets from investments and real estate in greater Philadelphia with the primary purpose of funding the continued operation of Girard College, which maintained the educational and philanthropic mission of Stephen Girard. Girard’s bequest, the largest trust given to the city, built on an already long history of charitable giving in Philadelphia that began with Benjamin Franklin and others in the eighteenth century. The lasting value of this foundational gift cemented Girard’s charitable legacy and raised the bar for philanthropy in the City of Brotherly Love.

Brenna O’Rourke Holland is Visiting Assistant Professor of History at the University of the Sciences in Philadelphia. She earned her Ph.D. in history at Temple University. Her dissertation, “Free Market Family: Gender, Capitalism, and the Life of Stephen Girard,” is a cultural biography of Philadelphia merchant-turned-banker Stephen Girard that interrogates the relationship between family and capitalism in the early American republic. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Girard College connects with activist who helped desegregate the school (WHYY, November 4, 2011)

- Stephen Girard documentary casts light on forgotten VIP (WHYY, December 5, 2011)

- Archeological dig on Delaware Avenue begins Monday (WHYY, July 14, 2012)

- Archeological dig on Delaware Avenue turns up timbers (WHYY, July 28, 2012)

- Judge bars changes at Girard College (WHYY, August 26, 2014)

Links

- PhilaPlace: Girard College: Breaking Down the Color Barrier of Girard College (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Stephen Girard Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Stephen Girard: A Philadelphia Legacy (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- 200-Plus Years Of Transforming Girard Square (Hidden City Philadelphia)