Great Wagon Road

Essay

Following routes established by Native Americans, the Great Wagon Road enabled eighteenth-century travel from Philadelphia and its hinterlands westward to Lancaster and then south into the backcountry of Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina. In search of affordable farmland and economic opportunity, thousands of Scots Irish, Germans, and others left the Philadelphia region to establish farms, taverns, villages, and new lives along the rugged road that stretched across southeastern Pennsylvania and eventually continued more than four hundred miles through the Shenandoah Valley of the Appalachian Mountains and beyond. The new population of the backcountry sustained connections with Philadelphia through trade, often facilitated by merchants in market towns such as Lancaster and York in Pennsylvania, Hagerstown in Maryland, and Winchester in northern Virginia.

The Great Wagon Road saw its most intensive activity in the middle decades of the eighteenth century, prior to the American Revolution. During this period, the increasing population of Pennsylvania made land more scarce and costly, not only for new arrivals but for settled farmers seeking to secure livelihoods for future generations. At the same time, governors in Maryland and Virginia were promoting backcountry settlement by Europeans as a means of securing their frontiers. A flow of settlers began by the 1720s, a decade of high immigration of Germans and Scots Irish into Pennsylvania, then increased dramatically after the 1744 Treaty of Lancaster settled Iroquois Nation claims in the Shenandoah Valley. A German migrant through Philadelphia, Jonathan Hager (1714-75), bought land in Maryland in 1739 and subsequently founded Hagerstown. The colonial governors of Maryland and Virginia sped settlement by awarding large land grants to individuals on the condition that they recruit specified numbers of migrants. For example, New Jersey speculator Benjamin Borden (1675-1743), born in Monmouth County, moved to the northern Shenandoah Valley by 1734 and received a grant of 100,000 acres on the James River for his pledge to recruit settlers from Ireland. Jost Hite (1685-1761), a German immigrant living on the Perkiomen Creek northwest of Philadelphia, received a grant of 140,000 acres and agreed to recruit 140 families. Their settlement in Virginia, together with Quakers who migrated to a similar grant made to Alexander Ross (1682-1748) from Chester County, led to the founding of the new town of Winchester.

Barely a Road

In its earliest days, the Great Wagon Road could hardly be termed a “road.” The Indian trails that it traced for much of its length originated as pathways for individuals walking in single file. The subsequent road developed from the traffic of more individuals, people on horseback, herds of cattle, carts pulled by animals, and eventually the heavy-duty Conestoga wagons that became the freight-haulers of the road. In places, the route consisted of not a single road but of variations created by travelers to avoid hazards or reach new destinations. The journey required fording or ferrying across rivers along the way. The Pennsylvania portion of the Great Wagon Road roughly followed the Great Minquas Trail used by Lenni Lenape, Susquehannocks (Minquas), and European traders. During the middle eighteenth century, travelers on this route between Philadelphia and Lancaster (founded in 1729) found a stump-punctuated dirt road despite its designation as a “King’s Road.” As the road turned south after Lancaster and York (founded 1741), it approximated the route known to Europeans as the Great Warriors’ Path, created and still valued by Native Americans for passage through the Shenandoah Valley west of the Blue Ridge. Past the Shenandoah Valley into western Virginia and the Carolinas, additional branches of the road often consisted of little more than tromped grass, mud, and the wagon ruts of previous travelers.

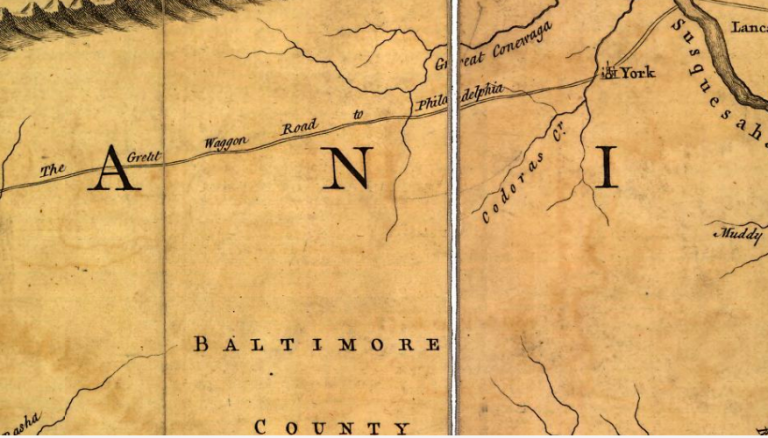

Despite its rugged conditions, “the Great Waggon Road to Philadelphia” appeared designated as such in 1753, on A Map of the Inhabited Part of Virginia containing the whole Province of Maryland, with Part of Pensilvania, New Jersey and North Carolina. By that time, the road had enabled a multiethnic ribbon of back-country settlement reaching from Pennsylvania south to the Yadkin River of North Carolina. In addition to the dominant Germans and Scots Irish, the settlers of the backcountry included Quakers who clustered around Winchester, Virginia (which sheltered exiled Philadelphia Quakers during the American Revolution). German-speaking Moravians from Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, founded the community of Wachovia in western North Carolina in 1753. By 1780, the southern backcountry had an estimated population of about 380,000, including the Pennsylvania migrants as well as English, French Huguenot, German, and Highland Scot settlers who moved inland from coastal Virginia and the Carolinas. The Great Wagon Road also enabled journeys through the region, for example by socially elite travelers seeking the resort springs of western Virginia.

Towns Spaced a Day’s Journey Apart

While most migrants came to establish farms in the broad valley between the backcountry’s mountain ranges, towns also developed at intervals along the Great Wagon Road in Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina. Spaced approximately one day’s journey apart, often founded by former Pennsylvanians and at times with street grids and center squares reminiscent of Philadelphia, towns anchored the backcountry as a market area for Philadelphia trade. They usually developed where the Great Wagon Road intersected with east-west roads from coastal regions. The resulting network of roads made it possible for wheat farmers in the backcountry to take harvests east to market in Alexandria or Richmond, Virginia, but bring back the profits to spend on finished goods imported by local merchants from Philadelphia via the Great Wagon Road. Towns along the Wagon Road served as points of transfer for crops bound for market in Philadelphia, including wheat and flour further exported from Philadelphia to Europe. Peddlers plied their trade along the road, and drovers moved herds of cattle to Philadelphia butchers. Philadelphia merchants and banks extended credit to backcountry businesses and land investors.

The Great Wagon Road became a pathway of settlement deeper into the western frontier after 1769, when Pennsylvania-born Daniel Boone (1734-1820) opened the Wilderness Road from North Carolina west into the territory that became Tennessee and Kentucky. Born in the rural reaches of Philadelphia County that later became Berks County, Boone migrated to North Carolina with his Quaker family at the age of 15. He gained fame as the trailblazer of the pass through the Cumberland Gap, thereby connecting the Great Wagon Road to points west.

The Great Wagon Road declined in importance with the development of additional improved roads and then railroads in the early nineteenth century. With some variations in route, it became the Lancaster Turnpike (incorporated 1792) in Pennsylvania and the Valley Turnpike (incorporated 1834) in Virginia. In the twentieth century, U.S. 30 in Pennsylvania and U.S. 11 and Interstate 81 through the Shenandoah Valley approximated the route of the Great Wagon Road. Testaments to connections with the Philadelphia region persisted in the form of surviving eighteenth-century houses, roadside historical markers, Pennsylvania-style bank barns, and towns with Presbyterian and Lutheran churches founded by Scots Irish and German settlers. The old road remained a subject of interest for scholars and a source of heritage tourism, and knowledgeable locals could still point out ruts and trenches believed to be remnants of the original road that linked Philadelphia to the settlement of the backcountry South.

Charlene Mires is Professor of History at Rutgers-Camden and Editor-in-Chief of The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University