I-95

By Dylan Gottlieb | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

Interstate 95—known as the Delaware Expressway in the Philadelphia area—is one of the region’s key transportation conduits. Running alongside the western bank of the Delaware River, it links central Philadelphia with Mercer County in New Jersey and Bucks and Delaware Counties in Pennsylvania. Conceived and built in an era when planners promoted automobile traffic above all other considerations, I-95 has played a vital role in Greater Philadelphia’s highway network. Yet its history also reveals the costs and benefits of auto-dependent transportation, as individual convenience and economic growth were weighed against neighborhood and environmental destruction.

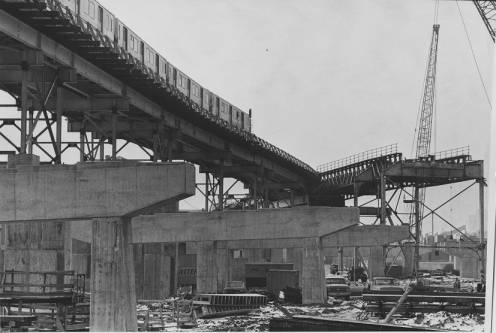

Planners had been proposing highways through the Philadelphia metropolitan area for decades before construction on I-95 began in 1959. Philadelphia’s City Planning Commission issued a design for an expressway along the Delaware River in the late 1930s, but those plans were scrapped due to concerns that it would interfere with the city’s shipping industry. After World War II, the Pennsylvania Department of Highways approved similar plans, this time for a toll-funded turnpike. With the passage of the 1956 Federal-Aid Highway Act, the federal government promised to fund ninety percent of the $200 million project, which would be built under direction of local agencies, including the Southeastern Pennsylvania Regional Planning Commission, Pennsylvania’s Department of Highways, and Philadelphia’s City Planning Commission and Department of Streets.

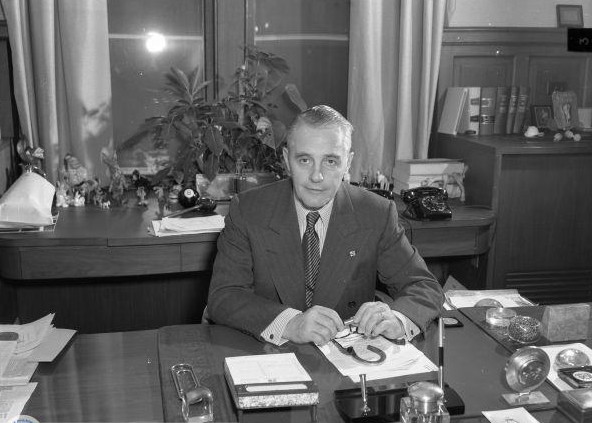

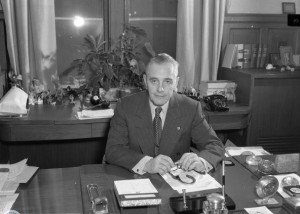

Designed as part of a planned loop of expressways around central Philadelphia, I-95 was intended to link the city’s riverfront with its factories and airport. The City Planning Commission argued that the expressway would “become in effect the conveyor belt of Philadelphia as a producing unit…it will provide access to the piers and the warehouses essential for operation of the port.” Planners also hoped that new highways would encourage people to drive downtown from the suburban fringe, helping to revitalize Philadelphia’s urban core. Highway planning gave precedence to suburban automobiles—not urban residents or pedestrians. As City Planning Commission Executive Director Edmund Bacon (1910-2005) remarked, “We think it better not to fight with the automobile…but rather to treat it as an honored guest and cater to its needs.”

When Pennsylvania’s Department of Highways unveiled its plans for the expressway in the late 1950s, city residents who lived in its path reacted with outrage. Middle-class residents of Society Hill, a historic area just beginning to undergo revitalization, organized to fight the expressway by forming the Committee to Preserve Philadelphia’s Historic Gateway. The committee proposed that I-95 should be built below street grade with a cover to block it from view and preserve pedestrian access to the river. After many years of wrangling, the state agreed to an amended plan in 1969. Instead of a continuous six-block cover, the expressway would be covered in two sections: one from Delancey to Dock Streets and another from Gatzmer to Chestnut Streets.

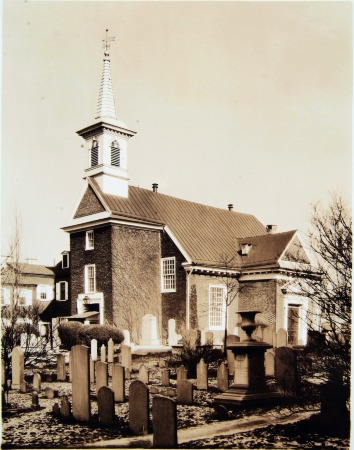

In Southwark, a working-class neighborhood on the South Philadelphia riverfront, construction of the expressway would prove more destructive. Plans necessitated the demolition of nearly 2,000 row houses and threatened the historic Gloria Dei (Old Swedes’) Church. In 1960, Mayor Richardson Dilworth (1898-1974) was heckled by 1,500 angry Southwark residents when he attended a neighborhood forum to discuss the highway. The community’s protests proved ineffective, however. Unlike the well-connected residents of Society Hill, they were unable to modify the proposed expressway. In 1966, demolition began in Southwark, where I-95 soon became a physical barrier between residents and the riverfront which had once provided jobs for thousands of area longshoremen.

While the first section of I-95—a six-mile stretch from Bucks Country to Woodhaven Road in Northeast Philadelphia—opened in 1964, delays continued to plague the project. There were contentious battles over where to place entrance and exit ramps in Central and South Philadelphia. Scores of protesters in Philadelphia’s Port Richmond neighborhood blockaded the off-ramp at Allegheny Avenue in 1969. The Philadelphia Inquirer quipped in 1970 that China’s Great Wall had been “built by hand at an average of 31 miles a year” while the Delaware Expressway was “being built by machine at an average of 2.9 miles a year.” At that glacial pace, I-95 was finally completed in 1979 (with the exception of a short segment near Philadelphia International Airport, finished in 1985).

Residents of New Jersey’s Mercer and Somerset Counties were even more dogged in their resistance to the expressway during the 1970s. Worried that I-95 would bring undesirable development to pastoral Princeton, Hopewell, and Montgomery Townships, wealthy residents banded together to fight the planned highway. In 1983, plans for the final segment of I-95 were scrapped; the expressway, designed to run continuously from Maine to Florida, stopped in central New Jersey. Drivers heading north from Pennsylvania towards New York City were forced to turn onto I-295 south when I-95 ended near Lawrence Township, New Jersey. In 2010, work began on a new link between I-95 and the Pennsylvania Turnpike in Bucks County, which would allow drivers to bypass the interrupted section of I-95 in Mercer County. When completed, the project would finally provide an unbroken highway connection between Philadelphia and New York.

Opposition aside, I-95 ultimately became a vital connection between Philadelphia and its neighboring cities and suburbs. The construction of the highway helped accelerate growth in Bucks County, where the population grew by thirty percent from 1980 to 2012. Developers built sprawling suburbs on former farmland. New business parks sprung up near I-95 exits in Bensalem and Bristol, and by 2009, nearly 30,000 Philadelphia residents commuted out of the city daily to jobs in the area. Traffic on I-95 grew along with Bucks County. In 1989, 90,000 vehicles per day used the expressway in Pennsylvania. By 2010, the same stretch carried 136,000 cars and 19,000 trucks per day.

In the 2000s, I-95 came under criticism again—yet this time, its detractors were not neighborhood residents, but urbanists concerned with environmental and lifestyle issues. Many Philadelphia planners argued that covering or removing the expressway would restore waterfront access and create acres of new valuable real estate. Inga Saffron (b. 1957), architecture critic for the Philadelphia Inquirer, summed up planners’ views in 2007 when she wrote that “Interstate 95 must change. Simple as that… .Bury it. Narrow it. Put a deck over it. Just get it out of our sight.” The debate over the future of I-95 exposed the growing rift between car-dependent suburbanites and city residents who valued walkability and recreational amenities.

Dylan Gottlieb, a Ph.D. candidate at Princeton University, works on recent American urban history. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- The City that Might Have Been: Edmund Bacon's Philadelphia (PhillyHistory.org)

- Statement by the President Upon Signing the Federal Highway Act of 1958 (The American Presidency Project at the University of South Carolina Beaufort)

- Inga Saffron: City's Biggest Block: The great I-95 divide (Philly.com)

- "The Construction of Interstate-95: A Failure to Preserve a City's History," by Alanna C. Stewart (PDF, University of Pennsylvania)

- Timeline: After 58 years Philly’s about to finally fix its I-95 problem (BillyPenn.com, March 3, 2017)