Ice Hockey (Professional)

Essay

In February 1966, the National Hockey League decided that the future was now. Responding to forces transforming other professional sports leagues, such as the growth of televised coverage and the expansion of franchises to the West Coast of the United States, the NHL decided to expand its static lineup of “Original Six” franchises in Eastern and Midwestern cities—Boston, Montreal, Toronto, Detroit, Chicago and New York. A new division of six expansion franchises, evenly distributed through all regions of the United States, reintroduced professional ice hockey in Philadelphia. Over the next fifty years, the Philadelphia Flyers transformed the region from a professional hockey wilderness to a hockey hotbed.

Philadelphia’s first foray into the NHL had been a failure of historic proportions. In 1931, the Pittsburgh Pirates hockey franchise, in deep financial distress, relocated to Philadelphia, adopting an orange and black color scheme and a new nickname—the Quakers. The team’s poor performance from the previous season— it had only won five games in 1929-30— continued into the 1930-31 campaign. The hapless franchise needed three games to score its first goal and nearly a month to notch its first win. The Quakers finished the season with a record of four wins, four ties, and a staggering thirty-four losses. The team’s .136 winning percentage stood as an NHL record until it was broken by the .131 percentage of the expansion Washington Capitals in 1974-75.

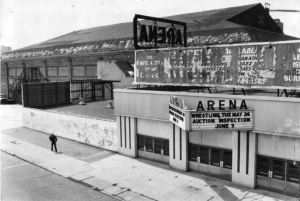

Despite more than a few opportunities, Philadelphia did not seem to like hockey. The Philadelphia Arena, which stood at Forty-Fifth and Market Streets from 1920 until 1983, hosted an array of minor league teams in a variety of leagues from the 1920s until the 1960s, none of which survived for very long. The longest-running franchise of this era was the Philadelphia Ramblers of the now-defunct Eastern Hockey League, which played in Philadelphia from 1955 until its move to Cherry Hill, New Jersey in 1964.

By the 1960s, Philadelphia was a city starved for a winner. A 1966 article in Sports Illustrated observed that “give them a chance, and people in Philadelphia would boo a funeral.” Brief glimmers of hope had been provided by the Eagles’ NFL Championship in 1960 and the 76ers National Basketball Association title in 1967, but the winning spirit did not last. The Phillies, in existence since 1883, had only made it to two World Series, losing both times and painfully throwing away a third opportunity in a tragic 1964 collapse.

Professional hockey returned to Philadelphia due in large part to the presence of Ed Snider (1933- 2016), a native of Washington, D.C., and vice president of the Philadelphia Eagles, who saw the NHL’s expansion plan as an opportunity. His limited exposure to the sport as a spectator had convinced him of the potential success of NHL franchise in Philadelphia. Snider, working with then Eagles owner Jerry Wolman (1927-2013) and New York investment banker Bill Putnam (1929-2002), began to assemble the resources to cover the NHL’s $2 million franchise fee (the equivalent of $44 million in 2016) and build a new 15,000 seat arena–later named the Spectrum— on an empty lot at Broad and Patterson Streets in South Philadelphia.

Ignoring the city’s spotty history with the sport, the NHL governors added the Philadelphia Flyers to the league, beginning play in the 1967-68 season. The city received the new team with indifference, at best. Area investors dismissed or ignored Snider and Putnam’s efforts to raise additional capital for the team, with one telling the owners, “Soccer will never go in Philadelphia.”

Even with financial support secured, the future of the franchise appeared in doubt. Philadelphia Mayor James Tate (1910-83) sent only a deputy to welcome the team formally to the city, and a parade down Broad Street to the newly opened Spectrum arena attracted a “crowd” of twenty, one of whom vocally predicted that the team would move to Baltimore by December.

On the ice, the new franchise seemed destined to reverse the hard fortunes experienced by the other professional sports franchises in Philadelphia. Drafting wisely among league veterans and minor league players left unprotected by the Original Six franchises, the Flyers won the new Western Division in their inaugural 1967-68 season. For a city with an apparent dislike of hockey, fan attendance for Flyers games grew every season, beginning with an average of 9,625 fans for the first season and growing to an average of over 16,000 in an expanded Spectrum by the 1972-73 season.

In other ways, however, the franchise seemed bitten by the same bad luck. On March 1, 1968, the roof blew off of the Spectrum, forcing the Flyers to play the entire last month of their first season on the road. When the Flyers returned to the reinforced Spectrum for their first NHL playoffs that same year, they were brutally smashed out of the opening round by the rough-and-tumble St. Louis Blues.

Despite growing fan interest, team performance over next few seasons followed this same pattern. The first five Flyers teams all ended their campaigns with losing seasons, and their two subsequent trips to the NHL playoffs ended in opening round sweeps by the Blues and the Chicago Blackhawks.

By the early 1970s, owner Snider demanded a team that could win games and defend itself. General Manager Keith Allen (1920-2014), nicknamed “Keith the Thief” by Philadelphia sportswriter Bill Fleischman, deftly assembled a blend of skill and muscle that came to define the NHL of the 1970s. Taking advantage of the league’s first universal entry draft in 1969, the Flyers gambled on a heralded young center from the Western Hockey League, Bob Clarke (b. 1949). Despite his outstanding junior career, Clarke’s diabetes made him a substantial risk in the eyes of most NHL teams. One of the few Philadelphia athletes never booed by the city’s demanding fan base, Clarke blossomed into the skilled, relentless, and iron-willed heart and soul of Flyers teams that would soon leave an indelible mark on the region and its hockey fans.

Tying together this collection of players into a cohesive unit was head coach Fred Shero (1925-90) hired by Allen from the New York Rangers in 1971. Nicknamed “The Fog” due to his introverted personality and indirect methods of communication, Shero’s innovative methods turned a nondescript expansion franchise into a perennial contender. A longtime student of the Soviet style of hockey, he was the first coach to use video analysis and create a set system for his players to follow, among other innovations. A former boxer, Shero also encouraged the aggressive instincts of his teams, which fit into the increasing mayhem in NHL games and transformed the identity of the team.

Philadelphia Bulletin writer Jack Chevalier, covering a fight-filled road victory over the Atlanta Flames, used the phrase “Bullies of Broad Street” in his game report. Bulletin staffer Pete Cafone headlined the article, “Broad Street Bullies Muscle Atlanta,” and a legend was born. While the Flyers gained increasing attention and scorn for their rough style of play—enforcer Dave “The Hammer” Schultz racked up 348 and an NHL record 472 penalty minutes in consecutive seasons—they also began to win. The team notched its first winning season in 1972-73, and Clarke was named the NHL’s MVP.

The rapid growth of Philadelphia as a hockey hotbed encouraged area businessmen Bernard Brown and James Cooper to bring another professional franchise to the city. The Philadelphia Blazers, a member of the NHL rival World Hockey Association, began play in the 1972-73 season. Featuring several former NHL players, including original Flyers goaltender Bernie Parent, who was traded to the Toronto Maple Leafs in 1971, the Blazers hoped to draw fan attention away from the Flyers. The competition was short-lived; the Blazers’ inadequate home arena at the Philadelphia Civic Center failed to draw many fans, and the team did not stack up to the Flyers’ steadily improving roster. The Blazers relocated to Vancouver after only one year in Philadelphia and folded in 1975.

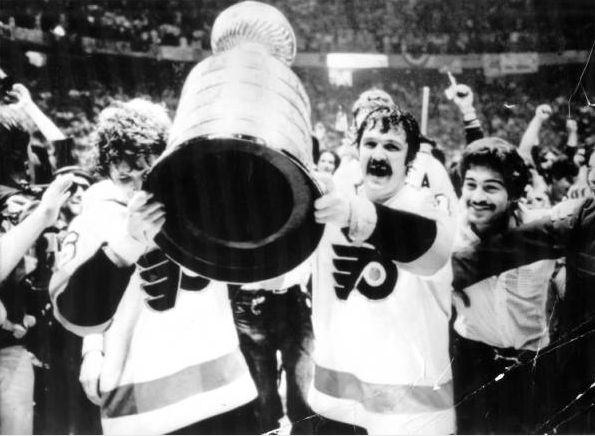

In 1973-74, reacquiring Parent as goalie provided the missing piece the Flyers needed. They won fifty regular season games and upset the heavily favored Boston Bruins in six games to win the seven-year-old franchise’s first Stanley Cup on May 19, 1974. Parent received the first of his consecutive Conn Smythe Trophies (MVP of the Stanley Cup playoffs) for his efforts in goal.

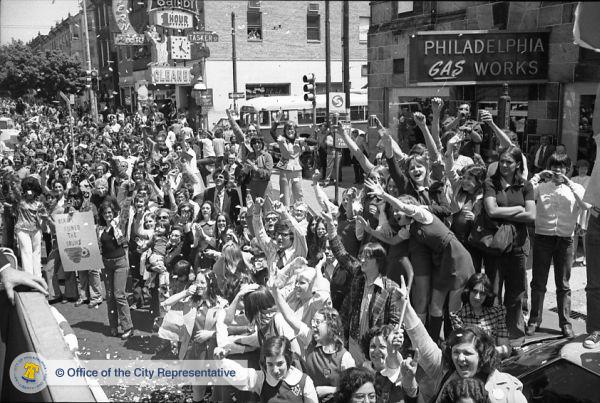

The team whose arrival in 1967 had been greeted with indifference unleashed a spectacle of celebration rarely seen in Philadelphia. Two million fans jammed Broad Street on May 20 for the team’s Stanley Cup parade, a throng only surpassed by the 2.5 million fans who celebrated the team’s second consecutive championship in 1975.

Although the Flyers’s consecutive Stanley Cup victories did not continue, they remained among the most successful franchises in the NHL. Valued at $660 million in 2015 by Forbes Magazine, their winning percentage of .578 through 2015 stood second among active teams all time, and they achieved sixteen division championships and six additional appearances in the Stanley Cup finals between 1975 and 2016.

Much changed after the heyday of the 1970s. The Spectrum was torn down in 2011 and replaced by the modern 20,000-seat Wells Fargo Center. The reach of the Philadelphia Flyers extended well beyond their home rink in South Philadelphia and beyond the team’s impact on expanding NHL rules against fighting. Prior to the 1967 expansion, almost all of the players on NHL rosters hailed from Canada. By 2016, slightly less than half of NHL players were from Canada, with nearly 25 percent being born in the United States.

As the Flyers grew in popularity, so did the number of ice rinks and opportunities for young skaters in the region to follow their heroes into the NHL. The most notable, Flourtown, Pennsylvania, native Mike Ritcher (b. 1966), grew up idolizing Parent and backstopped the New York Rangers to a Stanley Cup championship in 1994. From South Jersey, the National Hockey League also gained stars Bobby Ryan (b. 1987) of the Ottawa Senators and Johnny Guardreau (b. 1993) of the Calgary Flames.

Legendary Philadelphia sportswriter Frank Dolson (1933-2006) observed in 1981 that “professional hockey didn’t suddenly appear in Philadelphia after the Spectrum went up; it just seemed that way.” In 1967, many Philadelphians were unsure of the long-term viability of the Philadelphia Flyers. In 2016-17, the Flyers mark their fiftieth year of play in the National Hockey League in front of one of the most dedicated, knowledgeable, and passionate fan bases in the entire league. A gamble originally viewed as foolish evolved into a franchise that impacted all levels of sporting culture in the Philadelphia region.

Michael Karpyn teaches History, Economics, and Advanced Placement U.S. Government and Politics at Marple Newtown Senior High School in Newtown Square, Pennsylvania. He has served as a Summer Teaching Fellow at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, where he is a member of the Teacher Advisory Group. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Mark Howe on life, hockey and being 'Gordie Howe's Son' (WHYY, February 20, 2014)

- Hockey legend Bernie Parent reflects on his career, the Flyers, and the NHL lockout (WHYY, January 7, 2013)

- Ardent Flyers fans see the season as half-full (WHYY, January 7, 2013)

- Flyers faithful busting Penguins fans for a good cause (WHYY, September 14, 2015)

- Ed Snider Flyers legend dies at 83 (WHYY, April 11, 2016)

- Is Flyers' decision to erase Kate Smith a sign of the modern NHL? (WHYY, April 22, 2019)

Links

- Flyers History - How the Team was Named (NHL.com)

- Ice Skating, Philadelphia Pastime (HiddenCity Philadelphia)

- Philadelphia Spectrum Demolition (YouTube)

- A Look Back at 1974: The Big, Bad Bruins vs. the Broad Street Bullies (PhillySportsHistory.com)

- A Brief History of the Philadelphia Ramblers (PhillySportsHistory.com)