I’d Rather Be in Philadelphia

Essay

The expression “I’d rather be in Philadelphia” is derived from a fictional epitaph that locally-born entertainer W.C. Fields (1880-1946) proposed for himself in Vanity Fair magazine in 1925: “Here lies W.C. Fields. I would rather be living in Philadelphia.” By implying that Philadelphia would be slightly preferable to the grave, the joke tapped a vein of critical commentary about the city in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Variations of the witticism persisted in popular culture, but it did not ultimately find a place on the entertainer’s tomb.

Fields often lampooned Philadelphia, the boyhood hometown that he left to follow a career in show business. With the given name William Claude Dunkenfield (or Claude William, according to some sources), Fields was born in Darby, Delaware County, and grew up in a succession of rented row houses in West and North Philadelphia. After only a few years of school, he picked up odd jobs available to boys of his era: assisting in a cigar shop, hawking newspapers, delivering ice, shucking oysters, racking balls in billiard halls, peddling produce, and carrying cash between departments in the Strawbridge and Clothier store on Market Street. Frequently at odds with his father, he left home for at least a few months of his youth—a period he later embellished into tall tales of life on the streets as a vagabond.

Fields found his calling as an entertainer in Philadelphia’s theater district, which at the time thrived on North Eighth Street between Race and Vine. Captivated by the vaudeville shows of the 1890s, he taught himself to juggle and developed an act as “tramp juggler,” a silent hobo character who could adeptly toss cigar boxes, which became a hallmark of his act. After getting his start in venues like Natatorium Hall at Broad Street and Columbia Avenue, Plymouth Park near Norristown, and Fortescue’s Pier in Atlantic City, he attracted the notice of promoters of touring burlesque and vaudeville shows. With them, he performed nationally and internationally, gaining the skill and acclaim that led him to Broadway and the famed Ziegfeld Follies. The stage name he adopted, “W.C. Fields,” became his legal name in 1908.

By the 1920s, when Vanity Fair published his imagined epitaph, Fields was transitioning from pantomime juggler to character actor, comedian, and storyteller, not only on stage but in the emerging mediums of radio and the movies. Barbs about Philadelphia became a common part of the act. “I once spent a year in Philadelphia,” he said. “I think it was on a Sunday.” Or, “Anyone found smiling after the curfew rang was liable to be arrested.” In a later feature film, My Little Chickadee (1940), a character played by Fields described his last wish: “I’d like to see Paris before I die. Philadelphia will do.” His humor struck a chord among audiences accustomed to thinking of Philadelphia as sedate, old-fashioned, and corrupt—a perception that had been nurtured by such commentators as Charles Dickens (1812-70), who described the city as “rather dull and out of spirits”; Lincoln Steffens (1866-1936), who identified Philadelphia as “the most corrupt and the most contented” of cities; and Henry James (1843-1916), who referred to its “bourgeois blankness.”

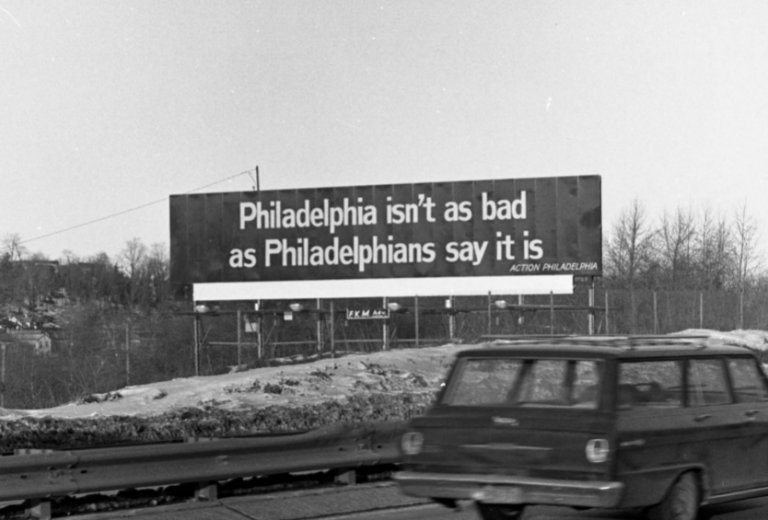

In later years, place-marketing and tourism promotion campaigns worked vigorously to counteract the image of Philadelphia embedded in Fields’ comedy. Still, variations of “I would rather be living in Philadelphia” persisted. While hospitalized in Washington after the 1981 assassination attempt on his life, President Ronald Reagan (1911-2004) scribbled on a note, “All in all, I’d rather be in Philadelphia.” Similar phrases cropped up in dialogue in the movie Die Hard (1988) and the television series Lois and Clark: The New Adventures of Superman (1993). “I’d Rather Be in Philadelphia” served as a title for a 1983 compilation rock album, a 1993 mystery novel by Gillian Roberts, and a 2007 episode of the television series Gilmore Girls. On the internet in the early decades of the twenty-first century, the expression appeared frequently as a touchstone for bloggers and as the title for a Twitter feed.

The comedy of W.C. Fields, while not flattering to Philadelphia, contributed to the city’s place in American popular culture even after the entertainer left the city behind. After his death, the marker on his vault at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California, bore the simple inscription: “W.C. Fields, 1880-1946.”

Charlene Mires is Professor of History at Rutgers-Camden and Editor-in-Chief of The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University