Labor Day

By Scott Hearn

Essay

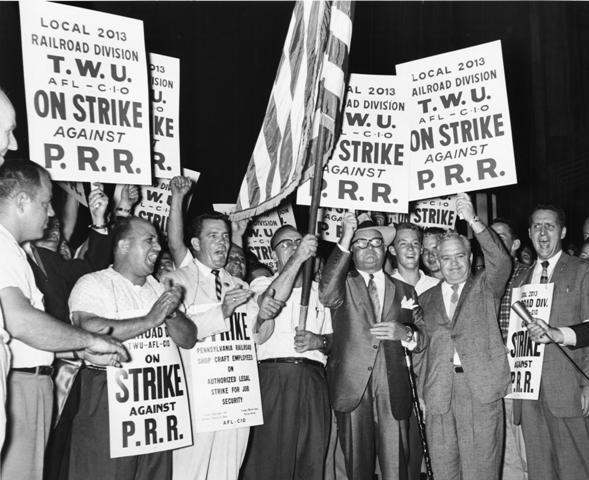

Labor Day, celebrated the first Monday of September, has been observed in the Philadelphia region since the 1880s, before it became a nationwide holiday. New Jersey was one of the first states to grant Labor Day legal status in 1887, and Pennsylvania followed suit by the end of the decade. The earliest incarnations of Labor Day grew from unrest among industrial laborers, but over time the holiday weekend also became a time for family activities and trips to the Jersey Shore.

The first celebration of Labor Day occurred in New York City on September 5, 1882, when an estimated 10,000 garment workers held a parade that ended in a picnic with labor-oriented speeches and family activities. The success of the first Labor Day led New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and other states to adopt similar celebrations and create legislated holidays. An act of Congress on June 28, 1894, made Labor Day a federal holiday. Two New York labor activists, Peter J. McGuire (1852-1906) of the American Federation of Labor and Matthew Maguire (1855-1917) of the Knights of Labor, both have been credited with the idea of making Labor Day a national observance.

In the Philadelphia area, Labor Day followed the pattern of the original observance in New York, with parades to show the solidarity of the workers followed by festivals for workers and their families. Dominated at first by the region’s textile unions, Labor Day attracted additional workers as the labor movement grew in prominence and the size of the parades and number of participants grew. In 1900, the region’s Labor Day celebration included 15,000 people from various ethnic and labor backgrounds celebrating together at Washington Park on the Delaware River in Gloucester, New Jersey. For several years, however, harmony among labor unions broke down and Philadelphia had two parades as workers became divided over supporting or opposing socialist parties.

Early Labor Day celebrations honored those who worked, but they also showed the power of the unions as they sought an advantage in negotiations over hours and wages. In 1905, the forces of labor reunited for a single parade of 30,000 laborers to show solidarity as most wage agreements were due to expire in May of the next year. The parade assembled at Broad Street and Girard Avenue and marched down Broad to Christian, then marched back into the city to Chestnut, to Delaware Avenue, to Arch Street, where the laborers took the Arch Street Ferry to Washington Park for family celebrations. While the parade was a key feature in this and other years, speeches by labor officials and politicians after the parades called attention to the condition of workers before unionization and focused on the civic and economic values behind the holiday.

In the early twentieth century, Labor Day changed as the growth of public transportation systems and automobile ownership allowed many city-dwellers to travel over the holiday weekend. Trips to the beaches of southern New Jersey became a tradition of Labor Day celebrations in the area. In 1914, for example, Atlantic City expected 50,000 or more Philadelphians to make the trip to the shore.

Labor Day also changed with transitions in the industrial economy. Celebrations were low-key and quiet during the Great Depression, even though membership in labor unions grew. With the economy fragile and the availability of work limited, workers did not want to risk their jobs. With the start of World War II, industry boomed and the economy recovered, and Labor Day returned to its pre-Depression style of celebration. Southern New Jersey beaches continued to be popular destinations with attractions for the entire family. The Labor Day parade remained a staple of the holiday but changed in scope to become more patriotic and family-oriented while still showing worker solidarity. Labor Day also changed significantly as the Philadelphia region shifted from production to the service economy, which meant fewer manufacturing jobs but a growing prominence of unions representing government employees, teachers, and others in the public and service sector.

The ideas of workers’ rights and solidarity associated with the first Labor Day celebrations continued to resonate with some, but as the Philadelphia area suburbanized, Labor Day celebrations became smaller and dispersed through many small towns. Big city parades, whether in Philadelphia or Wilmington, Delaware, did not attract as much attention. The holiday became associated more with commercial sales and end-of-summer rituals than with the interests of labor. During election years, it also signaled the kick-off of political campaigning as candidates participated in Labor Day events to connect with voters. Beginning in 2012, the Made in America music festival on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway became a hallmark event of Labor Day weekend in Philadelphia. Although union rallies continued to occur, the view of Labor Day as an extended weekend to be spent with family or on the beach remained a mainstay in the region.

Scott Hearn earned his master’s degree in history at Rutgers-Camden. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2014, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- City of Philadelphia Pleased with Made In America's Second Year (WHYY, September 3, 2013)

- Poll: Half of Americans like labor unions, while job satisfaction rises from recession low (WHYY, August 29, 2014)

- Joe Hill, songwriter for union crowds remembered in South Philly (WHYY, September 7, 2015)

- At Philadelphia Labor Day parade, federal and state investigations loom large (WHYY, September 5, 2016)

- In a year of labor pains and gains, Philly union members march (WHYY, September 4, 2018)