Lehigh Valley

Essay

Over the centuries, strong ties of transport, investment, and culture grew between the Greater Philadelphia region and the Lehigh Valley. The valley was carved by retreating glaciers twenty thousand years ago and maintained by its namesake river running from the Pocono Mountains, through Blue Mountain, south and east into the Delaware River. Only in recent memory was the region defined as the three counties of Carbon, Lehigh, and Northampton, and the metropolitan areas of Allentown, Bethlehem, and Easton.

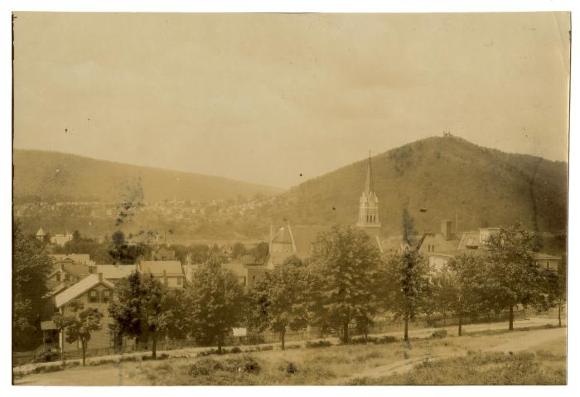

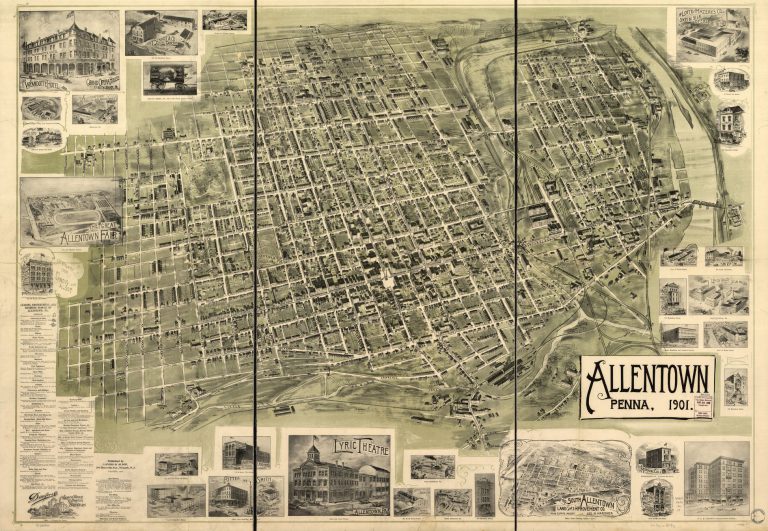

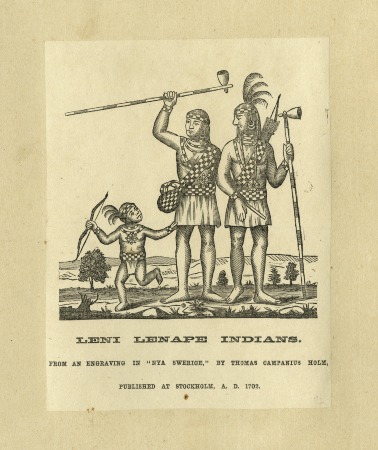

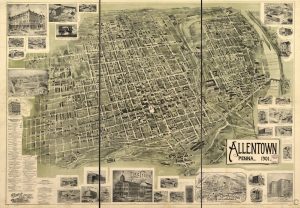

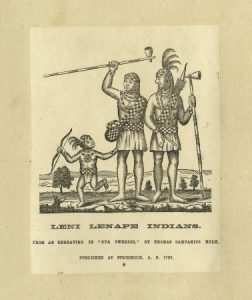

The Minsi Trail pathway linked elements of the Lenni Lenape tribe of Native Americans living in the Delaware, Lehigh, and Lackawanna river valleys. This trail, used for trade, communication, and tribal war, led the first Europeans to the valley in the early eighteenth century. The Lenape were forced from the valley after it was granted to the colony of Pennsylvania by the 1737 Walking Purchase. Evangelist George Whitefield (1714-70), Chief Justice William Allen (1704-80), and several wealthy Philadelphia investors purchased large tracts of the land in order to build country estates. Whitefield and Allen eventually sold their lands to settlers who developed communities in the region. Moravian missionaries settled Nazareth in 1740, and sect leader Count Nicolaus Zinzendorf (1700-60) founded Bethlehem in 1741. Allen, himself, planned Allentown (originally Northampton Town) in 1762.

Minsi Trail became known as the King’s Road and was maintained at the colony’s insistence by local communities. It spurred trade, making the valley a major supplier of furs, timber, iron, and agricultural products to Philadelphia. Pennsylvania recognized the region’s importance in 1752 by organizing it as Northampton County and naming Easton as the county seat. German immigrants followed the Moravian and Pennsylvania settlement efforts and filled out much of the valley’s land by the time of the American Revolution.

In the War for Independence the valley was the site of a Continental Army hospital and a state armory, and provided foodstuffs and supplies to the war effort. Durham Iron Furnace, owned by Irishman George Taylor (c. 1716-81), produced artillery and ammunition, and Taylor served in the Continental Congress and signed the Declaration of Independence. When the British occupied Philadelphia in the winter of 1777-78, the state moved several manufacturing operations to Bethlehem, and Allentown was used to warehouse Philadelphia’s many church bells. Most famously, the Pennsylvania State House bell, later known as the Liberty Bell, was stored in Allentown’s Zion German Reformed Church.

Stagecoach Service

After the war, the valley’s connections to Philadelphia increased. The beginning of regular stagecoach service in 1796 and the chartering of a turnpike company to manage the route in 1804 transformed the King’s Road into Bethlehem Pike. The 1791 discovery of coal in the region drew investment from Philadelphia, whose entrepreneurs Josiah White (1781-1850) and Erskine Hazard (1790-1865) chartered the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company to develop the coal field and built the Lehigh Canal between 1818 and 1829. The canal remained in operation until the 1940s, moving coal and iron to Philadelphia’s extensive factories and workshops.

Lehigh County was founded in 1812 and Carbon in 1843 as development in the region strained communications with Easton. Many local residents, however, considered federal, state, and Philadelphia city involvement in the valley detrimental to local morality and culture. The Fries Rebellion erupted in 1799 after a federal house tax was zealously enforced. Arrests for non-payment provoked John Fries (c. 1750-1818) to lead his fellow Lehigh Valley citizens in an armed attack on the Bethlehem jail holding the tax dodgers. Fries and others were tried and sentenced to death but pardoned by President John Adams (1735-1826). Political conflict replaced armed uprisings in the nineteenth century as the valley fought against state laws mandating public schools, missionary Methodist expansion, and outside investment in natural resources. But the valley could not stop Philadelphians’ investment and interest in the region.

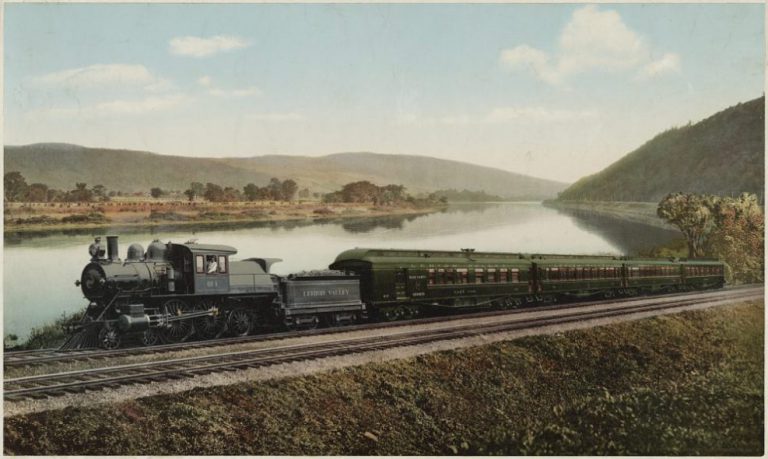

In 1852, the North Pennsylvania Railroad further linked the valley with Philadelphia. The Reading Railroad then leased that line and built the Perkiomen Railroad and East Penn Railroad to connect various segments of the valley to the greater Philadelphia region. Asa Packer (1805-79), however, controlled valley rail traffic by creating the Lehigh Valley Railroad in 1853 from rights-of-way he purchased from Philadelphia investor Nicholas Biddle (1786-1844). These rail routes served to develop various valley industries including cement making, slate mining, and iron and zinc smelting. Crayola, founded in 1885, and Just Born Quality Confections, founded in 1923, used the valley’s rail networks and access to resources to provide creative color toys and candies, respectively, to the Philadelphia region and outward to national markets. In 1857, Philadelphian Joseph Wharton (1826-1909) founded the Saucon Iron Company, which became Bethlehem Iron in 1861 and Bethlehem Steel in 1899. The steel company, until its 1995 closure, provided for Philadelphia’s manufacturing enterprises and for the Delaware River (later Benjamin Franklin) Bridge, built in 1926.

Philadelphia, however, was not the valley’s only customer. Bethlehem Steel provided beams and cable for buildings and bridges around the country, including the Golden Gate Bridge, the George Washington Bridge, the Chrysler Building, and Hoover Dam. Crayola Crayons were marketed around the world and were inducted into the National Toy Hall of Fame in 1998. Similarly, Just Born, started in New York, was given the key to the city of San Francisco for the innovativeness of its products. Passenger transport in the valley was developed by numerous trolley companies, one of which, the Lehigh Valley Traction Company, began service to Philadelphia, known as the Liberty Bell Line, in 1903. Two years later the company purchased and united all local routes as the Lehigh Valley Transit Company, making it possible to travel from Philadelphia to any part of the valley. Trolley service lasted until 1956 when post-World War II developments in bus service and personal cars made the rails unprofitable. Many of the Transit Company’s rights-of-way in the Valley were transferred in 1970 to Philadelphia’s transport company, the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA). In 1926, Bethlehem Pike was redesignated as Pa. Route 309 and upgrades began, with segments transformed into highways. Some parts were left to local use and named Old Bethlehem Pike. In 1955, an extension was added to the Pennsylvania Turnpike providing a second road link between the Philadelphia region and the valley.

Becoming a Bedroom Community

The construction of Pa. Routes 22 and 78 from the 1950s to the 1970s remade the valley into a New York City bedroom community. Commuters followed the highways west to avoid high costs of living, and bus service developed to transport workers into New York. Likewise, by the 1990s numerous New York firms relocated to the valley or built transport hubs to make use of the workforce and road network. In 2010, the U.S. Census Bureau recognized the importance of this economic and cultural connection by including the valley as part of the New York Metropolitan Statistical Area. Built in 1929, the Lehigh Valley International Airport connected the region to further non-Philadelphia markets and investors. The airport’s location and local intermodal service attracted Amazon, FedEx, and Air Transport International to make the valley a shipping hub for their enterprises.

Nevertheless, the valley retained strong cultural and economic ties to Philadelphia as well. Pennsylvania Power and Light (PPL), founded in 1920, provided electricity to several communities in the outlying Philadelphia region and was a major founding sponsor of the city’s professional soccer team, the Philadelphia Union, which played in Talen Energy Stadium, named after a PPL subsidiary. The Lehigh Valley Phantoms minor league hockey team, farm team to the Philadelphia Flyers, began playing in Philadelphia before moving to Allentown in 2014. Minor league baseball’s Ironpigs arrived in the valley in 2008 after becoming a farm team for the Philadelphia Phillies.

The valley was also served by Philadelphia’s major media outlets, and numerous health insurance, banking, and engineering firms had shared offices between the valley and Philadelphia. St. Luke’s Health Network of Bethlehem and Good Shepherd Rehabilitation Hospital of Allentown both invested in serving the Philadelphia region. The federal government stressed the connection between the two regions by creating the Delaware and Lehigh National Heritage Corridor in 1988, building a park and bike trail system over the unused canal and rail paths that previously linked the areas.

Investors saw the valley as a location to build hubs of transport, communication, and entertainment. In 2007, Sands Casino Resort purchased a large portion of the former Bethlehem Steel site and developed it into a $400 million gaming, live entertainment, hotel, and shopping destination. Opening in 2009, the site drew visitors to the Valley from both Philadelphia and New York. Sands became a major sponsor of Musikfest, an annual ten-day summer celebration of all music types. Started in 1984, in 2016 it hosted over nine hundred thousand people. It was created by ArtsQuest, a valley creative arts nonprofit that worked with Sands to develop the Steel Stacks Event Center on the old Bethlehem Steel site for both Musikfest and year-round programming. Remaining Bethlehem Steel properties as well as former industrial sites around the valley were purchased by the Lehigh Valley Industrial Park, an organization created in 1959 to revitalize the valley’s economic prospects as traditional enterprises declined. LVIP developed its section of the Bethlehem Steel site into office space, intermodal service, and storage. This investment drew companies like Norfolk Southern, Cigars International, WHEMCO (Lehigh Heavy Forge), and United States Cold Storage to the Valley. Philadelphia shoppers were further drawn to the region by the opening in 2006 of the Promenade Shops at Saucon Valley, which featured fifty-eight premium outlet stores.

Higher Education and Health Care

Much of the valley’s redevelopment was also due to its institutions of higher learning and health care. Moravian College, founded as a women’s seminary in 1742, played a major role in strengthening Bethlehem’s historic core. Lafayette College was founded in 1826 and in 1832 Easton’s town fathers convinced Reverend George Junkin (1790-1868) to relocate his Manual Labor Academy from Germantown to become part of the college. Lafayette subsequently became the city’s cultural heart. Muhlenberg College, founded 1848, and Cedar Crest, founded 1867, promoted Allentown as an undergraduate destination. Asa Packer (1805-1879) joined the development of education in the valley by opening Lehigh University in 1865 to provide engineers for his railroad.

Lehigh picked up the research mantle left by Bethlehem Steel, taking over its innovation center and promoting cultural events on Bethlehem’s South Side. Among the largest educational institutions in the Valley, however, were Northampton Community College (NCC) and Lehigh Carbon Community College (LCCC), with roughly ten thousand and six thousand students respectively as of 2022. They took leading roles in redeveloping the downtowns of Bethlehem and Allentown, respectively. NCC rehabbed an old Bethlehem Steel structure into an educational and community space. What began as Allentown Hospital in 1899 and a small St. Luke’s Hospital for Bethlehem’s South Side community in 1872 had by 2014 become the two largest employers in the valley. Lehigh Valley Health Network (LVHN) and St. Luke’s Health Network built dozens of facilities throughout the valley and beyond, expanding opportunity and infrastructure. Together they employed 4 percent of the valley’s population.

Throughout its development, the valley was an immigrant community. Following settlement by Moravians and Germans in the colonial period, Irish came to the region to work in the canals, railroads, and mines. Irish mine workers famously became known as the Molly Maguires, namesake of labor agitators whose leaders were hanged at the Carbon County Prison in Jim Thorpe. Irish immigration was quickly overwhelmed, however, by large numbers of Eastern Europeans, who came to work in the coal mines, iron furnaces, and steel mills. Churches and fraternal organizations located throughout the valley signaled the presence of two dozen different nationalities. Although African American workers were recruited to the valley during the world wars, more recently Latino immigration from Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic primarily surged, giving the region one of the largest Latino populations in Pennsylvania.

The Lehigh River Valley witnessed a great deal of development and change through the centuries. Lenni Lenape, Germans, Slavs, and Latinos each added distinctive marks to the land in terms of transport routes, educational institutions, industrial concerns, and entertainment options. The majority of this development tied the region to Philadelphia, but that did not keep the valley from becoming an economic and cultural hub in its own right.

Robert F. Smith, Ph.D., is Assistant Dean of Humanities and Social Sciences at Northampton Community College and author of the book Manufacturing Independence: Industrial Innovation in the American Revolution. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Extremely high levels of radon detected in Lehigh Valley homes (WHYY, November 21, 2014)

- Newest USL team to open play in Lehigh Valley next year (WHYY, August 19, 2015)

- Community land trusts across Pa. form collaboration (WHYY, March 30, 2016)

- In Allentown's Syrian community, scorn and support for Trump's travel ban (WHYY, January 30, 2017)

Links

- Allentown Art Museum

- National Museum of Industrial History

- Lehigh Valley Heritage Museum

- Moravian Historical Society

- Pennsylvania Mines and Mining

- Lehigh Valley Railroad Historical Society

- Redevelopment Achieves Mixed Results at Historic Site in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania (Cross Ties, Mid-Atlantic Regional Center for the Humanities, July 27, 2016)