LOVE (Sculpture)

Essay

The sculpture commonly known as “the LOVE statue,” first placed in Philadelphia’s John F. Kennedy Plaza for the 1976 Bicentennial, was not the only sculpture of its kind—by the twenty-first century, it was not even the only sculpture of its type in Philadelphia. Yet LOVE, by Robert Indiana (1928-2018), came to be embraced by Philadelphians and the city’s promoters as a distinctive icon for the City of Brotherly Love. Standing like a beacon thirteen feet high (six feet of artwork atop a seven-foot base), the colorful aluminum sculpture became a marker of identity for the surrounding plaza, increasingly known only as “Love Park.”

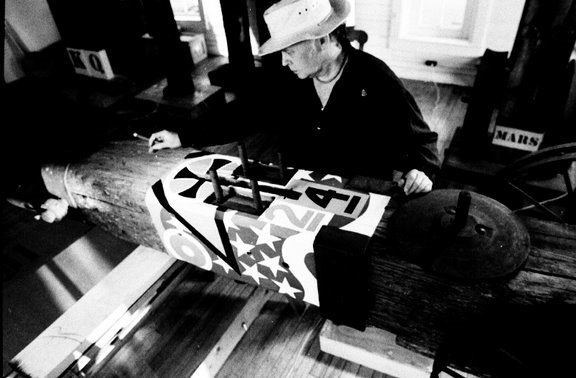

The LOVE design of four letters stacked in a square with a tilted “O” predated the Bicentennial, as did the artist’s association with Philadelphia. Indiana (who took the name of his home state) worked in New York, but his first single-artist museum exhibition occurred in Philadelphia in 1968 at the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) at the University of Pennsylvania. On the rise as a Pop artist, Indiana was working in a style he termed “verbal-visual,” in which words became elements of art. LOVE, which appeared at ICA in the form of paintings, prints, and a small sculpture, had been developing as a motif in Indiana’s art since 1961, when he created the design for a personal Christmas card and then for an immensely popular set of holiday cards issued by New York’s Museum of Modern Art. A subsequent LOVE poster for an Indiana show at New York’s Stable Gallery in 1966 further disseminated the design, which struck a responsive chord in the emerging counterculture of the 1960s. Along with love-ins, love beads, and other symbols of love and peace, Indiana’s work seemed symbolic of the times.

In addition to LOVE, the body of Indiana’s work displayed by ICA in 1968 included many other paintings, sculpture, and prints with themes drawing primarily upon American literature, current events, history, and popular culture. ICA director Stephen S. Prokopoff (1929-2001), one of the exhibition’s curators, viewed Indiana’s focus on American themes as harmonizing with Philadelphia’s history as a center for American art in the early nineteenth century. The catalog for the ICA exhibition contributed to later scholarship about Indiana’s work by including the artist’s “auto-chronology” of his life and work to that point in time.

By the early 1970s, LOVE came to overshadow Indiana’s other work as it circulated in many forms, as original art and in copies both authorized and unauthorized. The artist had come to the opening of the ICA exhibit sporting an 18-carat gold LOVE ring, one of series of 100 he had authorized to be made by Villanova-based Rare Rings, a new venture by Pop-art merchandise entrepreneurs Joan Kron and Audrey Sabol. For the cover of the novel Love Story (1970), another artist closely mimicked the colors and typography of Indiana’s design. Indiana himself produced versions large and small. A 12-foot-tall steel sculpture of LOVE, which became part of the permanent collection of the Indianapolis Museum of Art, traveled for exhibition in Boston and New York in 1971 and 1972. A 20-foot painting of LOVE appeared in an Indiana exhibition in New York. Indiana also created a miniature version of LOVE for a postage stamp, issued in time for Valentine’s Day 1973. Philadelphia, as the City of Brotherly Love, provided the setting for a first-day-of-issue ceremony held at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The U.S. Postal Service went on to sell more than 300 million of the eight-cent LOVE stamps. Intended to be red, green, and blue, the stamps turned out to be red, green, and purple—the result of overprinting blue over red.

The aluminum LOVE sculpture placed in John F. Kennedy Plaza, the public park at Fifteenth and JFK Boulevard near City Hall, featured the same colors as the stamp—red, green, and purple (replaced by blue during subsequent restorations but returned to the original purple in 2018). Indiana loaned the work to Philadelphia for the Bicentennial, a year also marked by the installation of Clothespin by another leading Pop artist, Claes Oldenburg (b. 1929), one block away at Fifteenth and Market Streets. LOVE, alas, proved to be fleeting. When the artist’s dealer recalled the sculpture to New York for a potential buyer in 1978, a public outcry ensued. City officials, who admitted to having no knowledge of the art market, had declined to pay the $45,000 asking price to keep LOVE in the park. Ultimately the price came down to $35,000, paid as a donation by Fitz Eugene Dixon Jr. (1923-2006), owner of the Philadelphia 76ers basketball team and chairman of the Philadelphia Art Commission. The Quaker Export Packaging Company donated its labor to retrieve the lost LOVE.

Secured again in John F. Kennedy Plaza, LOVE became a landmark and reference point in local geography. The Philadelphia Inquirer attributed the usage “Love Park” to homeless people who frequented the plaza during the 1980s. During the 1990s, “Love Park” gained widespread currency among skateboarders attracted by the varied levels of stone and concrete walls, steps, and benches of the plaza. Skateboarding videos and video games spread the image of LOVE in Philadelphia. By the time a thorough redesign and reconstruction of the plaza occurred in 2016-18, plans prioritized keeping LOVE in its place and termed the surrounding public space as JFK Plaza/Love Park. When the park reopened, “Love Park” appeared on banners and signs as a promotional brand.

Indiana continued to create LOVE sculptures into the late 1990s, including variations in other languages. By the twenty-first century, they could be found across the United States, in Israel, Europe, and Asia. In the Philadelphia region, the University of Pennsylvania and Lehigh University each had its own LOVE, and Ursinus College had a copy authorized by the artist. In 2015 for the visit of Pope Francis (b. 1936), the Philadelphia Museum of Art brought one of Indiana’s Spanish-language AMOR sculptures to the city, where it remained.

Philadelphia did not possess LOVE alone. Nevertheless, the sculpture became one of the city’s most recognizable icons, attested and reinforced by the steady flow of visitors seeking it out, posing for photographs, and placing themselves into a distinctively Philadelphia scene of LOVE.

Charlene Mires is Professor of History at Rutgers-Camden and Editor-in-Chief of The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2018, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Philadelphia welcomes more LOVE to the Parkway (WHYY, December 2, 2016)

- LOVE Park? More like loathe park! Criticisms mount as JFK Plaza slowly reopens (WHYY, April 25, 2018)

- Philadelphia’s LOVE statue artist, Robert Indiana, dies at 89 (WHYY, May 21, 2018)

- Robert Indiana’s complicated relationship with LOVE (WHYY, May 22, 2018)

- Starting this fall, LOVE Park will be open for wedding ceremonies (WHYY, August 16, 2018)

- LOVE Park keepsakes for sale, now in heart shapes and controversy free (WHYY, February 13, 2019)

Links

- LOVE (Association for Public Art)

- AMOR (Association for Public Art)

- Love Cross (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

- Love Statue (Visit Philadelphia)

- Robert Indiana

- LOVE, 1966-1999 (RobertIndiana.com)

- From the Archives: Holiday Cards from MoMA

- Art of the Stamp (National Postal Museum)

- Institute of Contemporary Art