Martin Luther King Jr. Day

Essay

Philadelphia has had a greater influence on Martin Luther King Jr. holiday traditions than any city other than King’s birthplace, Atlanta. Observed on the third Monday in January since 1986, the federal holiday commemorates King (1929-68) and his civil rights activism. Ceremonies at the Liberty Bell and a focus on community service are among Philadelphia’s contributions to the annual observance.

Interest in honoring King’s legacy grew after his 1968 assassination, and annual observances of his date of birth (January 15) began in Atlanta and elsewhere. Pennsylvania Governor Milton J. Shapp (1912-94) signed a state King Holiday into law in 1978, and New Jersey declared a state holiday the same year. Delaware Governor Pierre Samuel Du Pont (b.1935) designated a state holiday in 1984. Public pressure also persuaded Congress to pass federal King holiday legislation, which President Ronald Reagan (1911-2004) signed on November 2, 1983. Commemorating King’s birthday as a federal holiday beginning in 1986, the day was dedicated to reflecting on “racial equality and nonviolent social change.” Intended for all Americans, not only African Americans, King Day nonetheless fulfilled a long held desire for a national Black holiday.

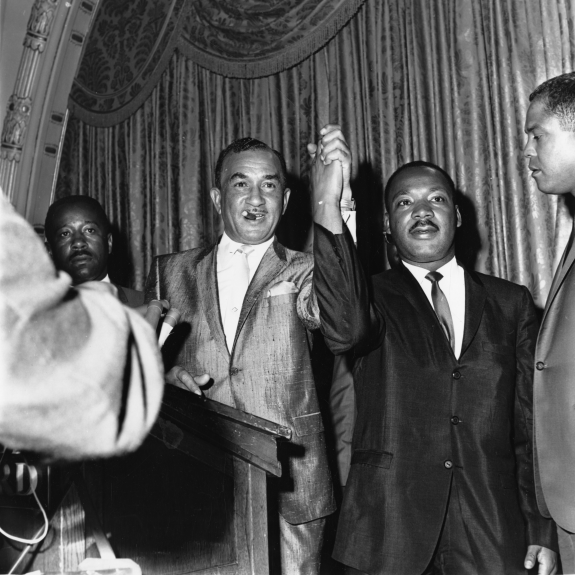

Philadelphia’s role in the observance grew after the first holiday, which was criticized by civil rights activists as superficial and overly reliant on King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. Seeking to make the day more substantial, the King Federal Holiday Commission chaired by King’s widow Coretta Scott King (1927-2006) looked to Philadelphia for inspiration and used the bicentennial of the U.S. Constitution to invoke King’s legacy. The Liberty Bell, with its associations to independence and abolition, became a holiday icon; ringing the bell, and replicas in every state, became a tradition from 1987. Some who gently tapped the bell in Philadelphia included Rosa Parks (1988), Benjamin Hooks of the NAACP (1989), James Farmer of the Congress of Racial Equality (1990), Dorothy Height of the National Council of Negro Women (1992), Vice President Albert Gore (1995), and General Colin Powell (1996). King himself had laid a wreath at the bell in 1959 on National Freedom Day to commemorate the Thirteenth Amendment.

Day of Tribute—and Protest

On King Day, traditions in the Philadelphia region have included ecumenical prayer services, songs, speeches, and acts of community service. Banks, public schools, and state and federal agencies close. The holiday has also been used to protest social and political conditions. Over the years, Congressman William H. Gray III (1941-2013) denounced apartheid in South Africa, the Philadelphia-Delaware Valley Union of the Homeless claimed an abandoned house in Southwest Philadelphia, and sanitation workers demonstrated against their employment conditions. C. Delores Tucker (1927-2005), president of the Philadelphia MLK Association for Nonviolence, also led a protest outside Tower Records to condemn misogynist lyrics in rap music.

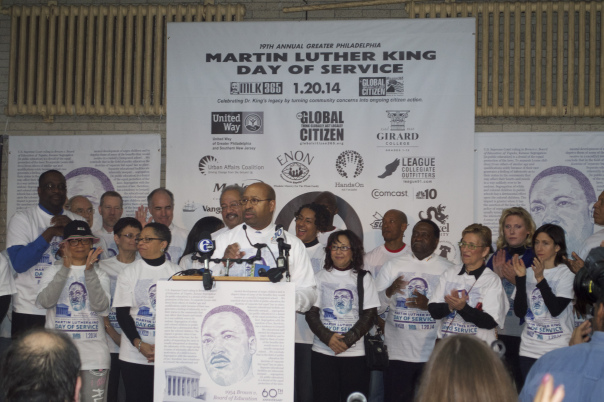

Philadelphia again influenced the national holiday in 1994 when U.S. Senator Harris Wofford (b. 1926) of Pennsylvania persuaded Congress to convert the holiday to a day of community service. Wofford had worked as a civil rights adviser to President John F. Kennedy and led the Peace Corps, an inspiration for the service initiative. Wofford highlighted Philadelphia’s existing community service events and with Coretta Scott King’s support he and Congressman John Lewis (b. 1940), a civil rights movement veteran, sought to transform the day into an “active living tribute” to King. They wanted “to remember Martin the way he would have liked” with “action, not apathy.” On August 23, 1994, President Bill Clinton (b. 1946) signed the King Holiday and Service Act, establishing the day of service.

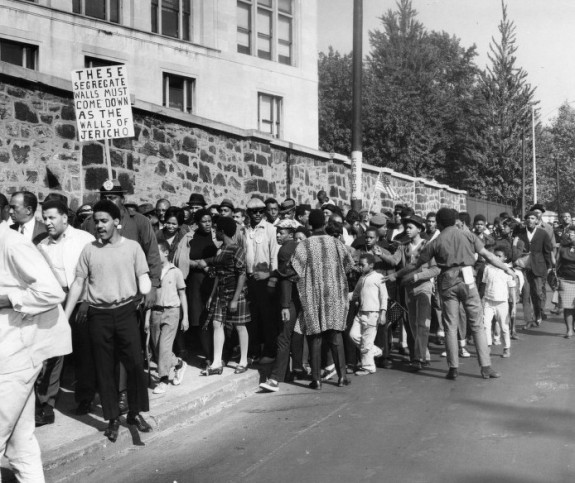

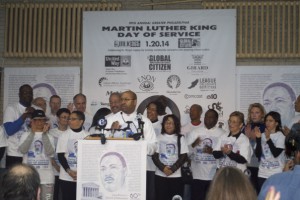

In Greater Philadelphia, service activities on Martin Luther King Day have been centered at Girard College, where King spoke before 5,000 at an integration rally in 1965. Activities have been coordinated by MLK 365, a project of the Philadelphia-based nonprofit organization Global Citizen. MLK 365 seeks to promote volunteerism not only on the holiday, but year-round, and hosts discussions on race, class and power.

The 2015 King holiday in Philadelphia encompassed protest as well as commemoration. A large rally marching up Broad Street to City Hall and on to Independence Hall marked Martin Luther King Day as a “Day of Action, Resistance, and Empowerment” against economic inequality and police brutality. Following several high profile deaths of Black men in other cities at the hands of police, this protest attempted to reclaim King’s activism and pointed to a potentially contentious future for the holiday as a new generation of King legatees sought to protest as well as to serve.

Daniel Thomas Fleming is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of History at the University of Newcastle, Australia. He is the author of “Remembering Martin Luther King Jr.” in Agora, Vol 46, No 1, 2011 and “Marvin Gaye, Martin Luther King and the FBI” in Traffic, Vol 9, 2007. He has presented his research at conferences of the Organization of American Historians and the Association for the Study of African American Life and History. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2105, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- King Day of Service - hailing and chasing the dream (WHYY, January 16, 2012)

- MLK Day is 'not just a day off from work' for volunteers at First Presbyterian (WHYY, January 17, 2012)

- MLK Day of Service brings out more than 100,000 (WHYY, January 21, 2013)

- MLK day of Service organizers gear up for another Philly record (WHYY, January 8, 2014)

- Nutter uses King Day speech to call for full funding of education (WHYY, January 20, 2014)

- Major march planned in Philly for MLK day (WHYY, January 8, 2015)

- Thousands march to 'Reclaim MLK' in Philly (WHYY, January 19, 2015)

- Activists relate to King's shift from dreamer to radical (WHYY, January 16, 2017)

- For Girard College's MLK Day of Service, a focus on solutions to gun violence (WHYY, January 22, 2019)

Links

- Philadelphia Martin Luther King, Jr. Association for Nonviolence (PhiladelphiaMLK.org)

- Greater Philadelphia Martin Luther King Day of Service (Global Citizen)

- Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. - Visit to Philadelphia (Temple University, Civil Rights in a Northern City: Philadelphia)

- The Meaning of the King Holiday by Coretta Scott King (The King Center)

- How Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s birthday became a holiday (National Constitution Center Blog)

- Things to Do for Martin Luther King Jr. Weekend in Philly (Visit Philadelphia, December 30, 2021)