Native Peoples to 1680

Essay

Native Americans lived in what became southeastern Pennsylvania, southern New Jersey, and northern Delaware for more than 10,000 years before the arrival of Europeans in the early seventeenth century. By emphasizing peace and trade, the Lenapes retained their sovereignty and power through 1680, unlike Native peoples in New England and Virginia who suffered disastrous conflicts with the colonists. Before William Penn founded Pennsylvania, the Lenapes and their allies among the Swedish, Finnish, and Dutch settlers created a society based on the ideals of peace, individual freedom, and inclusion of people of different beliefs and backgrounds.

The first Americans settled in the region as glaciers gradually receded in North America at the end of the last ice age. Because of the accumulation of ice, the Atlantic seashore was located more than sixty miles to the east of its present location. As the glaciers melted, the ocean level rose, submerging evidence of early communities along the coast. Archaeological data about the people inhabiting the lower Delaware Valley from this early era through the Woodland Period (c. 1000 B.C. to 1600 A.D.) indicate significant continuity over thousands of years. The Lenapes, like their ancestors, relied upon hunting, fishing, gathering, and—in the later years—small-scale agriculture. They lived in small autonomous towns without palisades, suggesting they kept mostly at peace with their neighbors and more-distant nations.

Isolation of the Lower Delaware Valley

For centuries the Native people of the lower Delaware Valley remained isolated from other parts of the Americas, including the peoples of the Ohio and Mississippi Valleys who built agricultural civilizations based on the “three sisters”: corn, beans, and squash. These crops complemented one another in cultivation and providing humans a nutritious diet. The geography of Pennsylvania, particularly the north-south orientation of the Susquehanna and Delaware Rivers, limited interaction of Delaware Valley natives with the Mississippians who built cities, tall burial mounds, and stratified societies in the interior of the continent. Though the Lenapes raised corn, beans, and squash by the time the Europeans came, the natives took advantage of the abundance of game animals, fish, shellfish, berries, wild rice, and other foods rather than engage in large-scale agriculture.

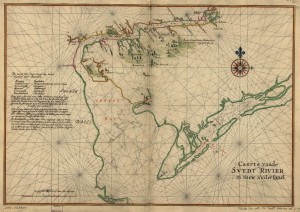

The Lenape people included groups such as the Armewamese, Cohanzicks, Mantes, and Sickoneysincks, who built towns along tributaries of the Delaware River and on the Atlantic seacoast near Delaware Bay. They spoke Unami, an Algonquian language similar to the dialects of their allies the Munsees, who controlled the region to the north up into southern New York, and the Nanticokes of Maryland’s Eastern Shore. The Lenapes’ neighbors to the west were the Susquehannocks, an Iroquoian people of the Susquehanna Valley.

The size of the precontact Delaware Valley population is unknown because European sailors and fishermen brought pathogens even before the Dutch arrived. Colonization of Europeans in North America had a devastating impact on the Lenapes and other natives because they lacked immunity to smallpox, influenza, measles, and other diseases. In 1600 the Lenapes numbered an estimated 7,500; by the 1650s their population decreased to about 4,000, and to about 3,000 by 1670. The Lenapes’ population decline was not as severe in the 1600s as among some other groups whose numbers dropped by ninety percent or more. The Lenapes’ success in avoiding war during most of the seventeenth century contributed to their strength and continued sovereignty over their land.

Lenape Gender Roles

The Lenapes divided work on the basis of gender: Women raised crops, gathered nuts and fruit, built houses, made clothing and furniture, took care of the children, and prepared meals, while men cleared land, hunted, fished, and protected the town from enemies. Native women held an equivalent status with men in their families and society; parents extended freedom to their children as well, practicing flexible, affectionate child-rearing.

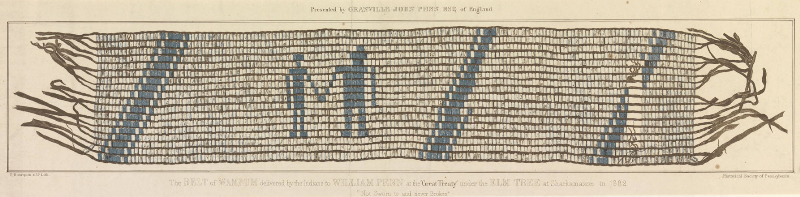

During the seventeenth century, the Lenapes’ sociopolitical structure appears to have been democratic, egalitarian, and based on matrilineal kinship groups, with descent through the mother’s line. The heads of kinship groups chose the group’s leader, or sachem, who held authority by following the people’s will. With advice, the sachem assigned fields for planting and made decisions on hunting, trade, diplomacy, and war.

In religion, existing evidence suggests that the Lenapes believed the earth and sky formed a spiritual realm of which they were a part, not the masters. Spirits inhabited the natural world and could be found in plants, animals, rocks, or clouds. Natives could obtain a personal relationship with a spirit, or manitou, who would provide help and counsel to the individual throughout his or her life. Lenapes also believed in a Master Spirit or Creator, who was all-powerful and all-knowing, but whose presence was rarely felt.

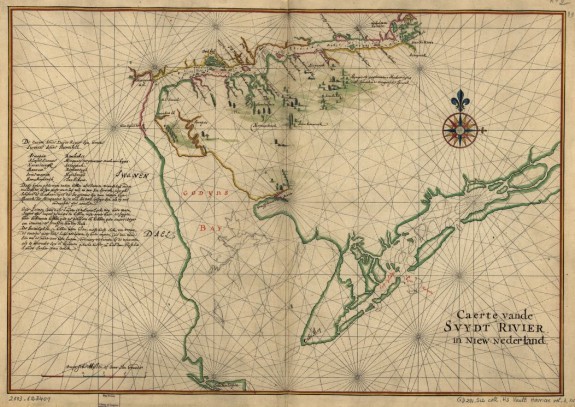

When Dutch explorers entered the Delaware River about 1615, the Lenapes welcomed their trade. In 1624, they granted permission for a short-lived settlement on Burlington Island and in 1626 allowed construction of Fort Nassau across the river from the future site of Philadelphia. The Lenapes and colonists developed a trade jargon based on Unami that became standard trade language throughout the region.

Keeping Old Ways, Adopting New

The Lenapes retained their autonomy and traditional ways of life while selectively adopting new technology from the Europeans. Native women and men appreciated the convenience of woolen cloth, firearms, and metal tools, incorporating them into their culture but not abandoning their traditional economic cycle of hunting, fishing, gathering, and agriculture.

The Dutch trade precipitated war between the Lenapes and Susquehannocks from 1626 to 1636 because the Susquehannocks sought to control the Delaware River. They killed many Lenapes and pushed them from the west to east bank, burning towns and crops. The Lenapes fought back, eager to trade for European cloth, guns, and metal goods in exchange for beaver, otter, and other furs. While these local pelts were thinner because of milder mid-Atlantic winters than those the Susquehannocks obtained from central Canada through the continental fur trade, the Lenapes had a successful market with the Dutch. The war ended by about 1636 when a truce, which developed into an alliance, permitted both the Lenapes and Susquehannocks to trade in the region.

In 1631, violence flared when wealthy Dutch investors started a plantation called Swanendael near present-day Lewes, Delaware, at the mouth of Delaware Bay. It seemed to Lenapes that the Dutch were shifting their priorities from trade to plantation agriculture similar to the English colonists in Virginia who murdered natives and expropriated land. The Sickoneysincks, the Lenape group near Cape Henlopen, destroyed Swanendael, killing its thirty-two residents. When Dutch captain David de Vries (1593-1655) arrived in early 1632, he made peace and reestablished trade with the Sickoneysincks.

Over the next half century, Lenapes controlled the lower Delaware Valley, accepting European trade goods in exchange for small parcels of land for forts and farms, but not plantation colonies. With the attack on Swanendael and its memory, the Lenapes restricted European settlement. In 1670, just 850 Europeans lived in the lower Delaware Valley compared with 52,000 in New England, 38,000 in Virginia and Maryland, and 6,700 in New York and eastern New Jersey. With an estimated population of 3,000 in 1670, the Lenapes remained more numerous and powerful than the Europeans.

New Sweden Established

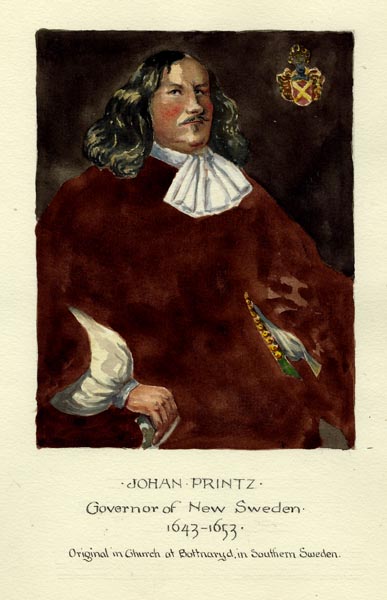

Seven years after Swanendael, in 1638, the Lenapes permitted a small group of Swedish, Finnish, and Dutch colonists to establish New Sweden at the location of current Wilmington, Delaware. Lenapes and Susquehannocks traded with New Sweden and the Dutch mariners who continued to frequent the river. While the Europeans fought each other over trade and land, the Lenapes dominated the region. In the mid-1640s they nearly evicted the Swedes because of their lack of trade goods and the bellicose posturing of their governor Johan Printz (1592-1663). Relations improved by 1654 when Naaman and other sachems concluded a treaty with the new Swedish governor, Johan Risingh (c. 1617-72), in which each side promised to warn the other if they heard of impending attack by another nation. They also pledged to discuss problems such as assaults and murders, stray livestock, and land theft before going to war.

By the 1650s, many of the Armewamese group of Lenapes lived adjacent to the Swedes and Finns in the area that became Philadelphia, a locale the Swedish engineer Peter Lindeström (1632-1691) praised for its beauty, freshwater springs, multitude of fruit trees, and many kinds of animals. Lindeström identified six towns from the Delaware to the falls of the Schuylkill that the Armewamese built to be near the terminus of the Susquehannock trade. The Lenapes also sold corn as a cash crop to New Sweden when its supplies ran short.

After the Dutch conquered New Sweden in 1655, the Lenapes, Swedes, and Finns solidified their alliance to resist heavy-handed Dutch authority. The Lenapes warned the Swedes of the Dutch assault; their Susquehannock and Munsee allies attacked Manhattan, forcing Director Peter Stuyvesant (d. 1672) and his troops to withdraw from the Delaware Valley. While the Dutch claimed the region, the Lenapes ruled their country in alliance with the Munsees, Susquehannocks, Swedes, and Finns.

With the English conquest of the Dutch colony in 1664, the alliance of Lenapes, Swedes, and Finns remained firm as together they resisted English efforts, under the Duke of York, to impose their power and expropriate land. In the late 1660s, the Armewamese left their towns where Philadelphia now stands, migrating to join the Mantes and Cohanzick communities in New Jersey. Though it is unclear whether settlers forced out the Armewamese or they left voluntarily, their relocation moved the center of Lenape population and power across the river.

In 1675-76, the alliance of Lenapes, Swedes, and Finns helped Lenape country escape the horrors of war similar to Bacon’s Rebellion in Virginia and King Philip’s War in New England. Through shared economic goals and common values of peace, individual freedom, and openness to people of different cultures, the Lenapes and their European allies established the ideals of Delaware Valley society before William Penn received his land grant for Pennsylvania in 1681.

Jean R. Soderlund is a Professor of History at Lehigh University and author of Lenape Country: Delaware Valley Society Before William Penn. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2014, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- Governor Printz Park Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.org)

- Lenape Nation Pennsylvania (Lenape Nation Website)

- The Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape (Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape Website)

- Native American Heritage Programs

- Native Languages of the Americas: Lenape (Native-Languages.org)

- New Sweden Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.org)