Octavia Hill Association

Essay

The Octavia Hill Association of Philadelphia was founded in 1896 to provide clean dwellings at reasonable rents to some of the city’s poorest residents, who were often exploited by profit-hungry landlords. Still active as a real estate management company, the Octavia Hill Association has a history of responding to changing economic conditions and housing needs.

Despite Philadelphia’s reputation as a “city of homes,” by the late nineteenth century many back alleys and courtyards were overcrowded with two- and three-story dwellings, with inadequate sanitation. Such poor conditions, particularly in the Southwark vicinity of South Philadelphia, drew the attention of Progressive-era reformers who wanted to assist African American and immigrant residents. Hannah Fox (1858-1933) and Helen C. Jenks, both members of the newly organized Civic Club of prominent women interested in the arts and social service, founded the Octavia Hill Association after attending a talk on slum conditions in the city’s fourth and fifth wards. These women, inspired by English reformer Octavia Hill (1838-1912), hoped to attract more than the usual charitable donations by promising investors a five-percent profit. Funds were used to purchase and renovate dwellings to be rented to families at a reasonable cost.

The two most important leaders of the Association during its first several decades were Fox and her friend and cousin Helen Parrish (1859-1942). Both women were connected to the white, upper class, and Quaker Parrish-Wharton family, which had a long tradition of social service. Fox and Parrish personally encountered the overcrowded and distressing conditions in South Philadelphia in the 1880s when they worked with Susan Parrish Wharton (1852-1928), founder of the St. Mary Street Library Association (1884). Susan, another of Helen’s cousins, was the daughter of Susanna Wharton, a social activist and friend of Octavia Hill. Fox and Parrish continued to support the St. Mary Street library but became convinced of the need for an organization devoted solely to improving housing conditions.

Following the model established by Octavia Hill, in 1888 Fox purchased two houses on St. Mary’s Street (now Rodman Street) and with Parrish refurbished and rented them to African American families. That same year, Parrish visited Hill in London for six months to observe her methods. Two decades earlier, with the encouragement of social critic John Ruskin, Hill had purchased several London houses to rent at fair prices to poor families. She established the pattern of housing reform known as “five percent philanthropy” (sometimes described as “four percent philanthropy”), combining philanthropy with limited profit to investors. Hill’s goal was to promote better housing conditions by purchasing and renovating clusters of dwellings that would create a sense of community and provide an example to surrounding neighborhoods. In line with an emerging reform tradition, Hill believed in the power of the physical environment to shape human values and attitudes.

“Friendly Rent Collectors”

In addition to decent housing and reasonable rents, Hill also hoped to eliminate the problems caused by absentee landlords. To establish personal relationships with the association’s clients, she introduced female “friendly rent collectors,” who visited families each month to instill thrift and responsibility. Hill, though, saw little to be gained by middle-class women actually living amidst poverty as settlement-house workers did. She believed that such constant immersion in the lives of the poor would make workers less objective in their assistance and less influential as exemplars of middle class values.

The Philadelphia reformers who named their association for Octavia Hill shared her belief in the power of environment and example; like her, they also rejected public subsidies (as non-educative) and, at first, multi-family housing. In 1911, Parrish argued that the single-family home in the form of the small row house was the “better method of housing, the only method that ultimately will offer a solution of the great housing problem.” To both purchase and renovate was expensive, so the Association also renovated and managed properties for other owners.

Tenants were expected to contribute both rent and their own effort to maintain the renovated dwelling. The Philadelphians were not as rigid as Hill about tenants meeting rent payments, but some workers attempted to intervene in their tenants’ behaviors. Settlement workers rented accommodations from the Association and often served as “friendly rent collectors,” minimizing distinctions Hill had thought important.

The Association’s first properties were located in Wards 2, 3, 4, 5, and 7. Wards 2, 3, and 4, located along the Delaware River just below South Street, were until the 1970s known as Southwark. Ward 5, also along the Delaware, was adjacent to Southwark on the north side of South Street, and Ward 7, just west of Ward 5, extended to the Schuylkill River. Ward 7, with a population that was about thirty percent African American by the 1890s, was made famous by W. E. B. Du Bois in his study The Philadelphia Negro (1899).

Dense and Congested

Increasing numbers of immigrants resulted in Southwark and adjacent Wards 5 and 7 containing about one-tenth of the city’s population in what was one-eightieth of the city’s area. At the turn of the twentieth century, the Third Ward, predominantly inhabited by Italian immigrants, was the most congested in the city, averaging 209 persons per acre. The growing housing problem and the high costs of purchase and renovation prompted Association members to reconsider the use of multi-family dwellings and undertake the management of Casa Ravello, owned by reformer Dr. George Woodward, a long-time Association board member. This four-story tenement, located on Seventh Street between Catherine and Fulton Streets, housed thirty-three Italian families.

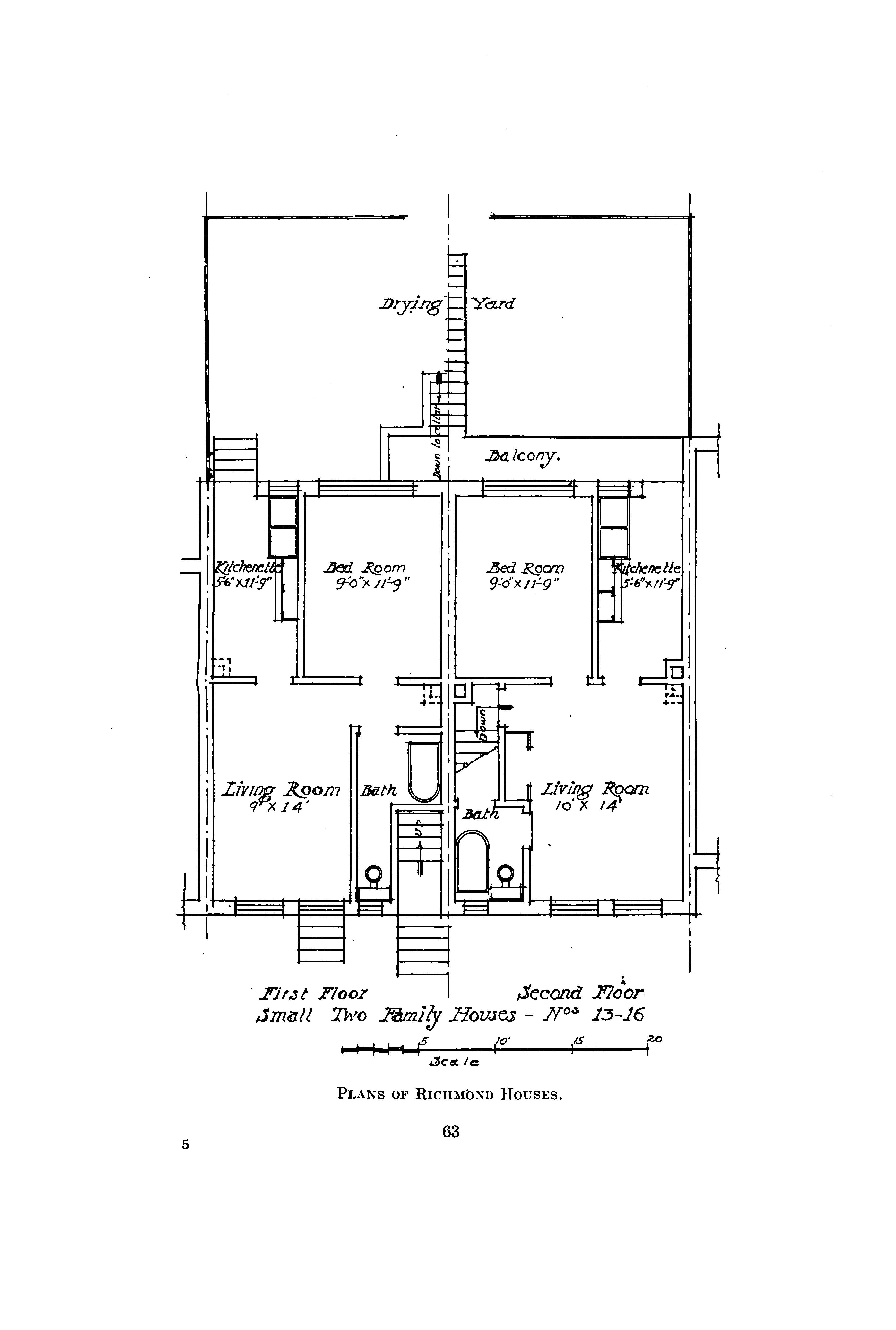

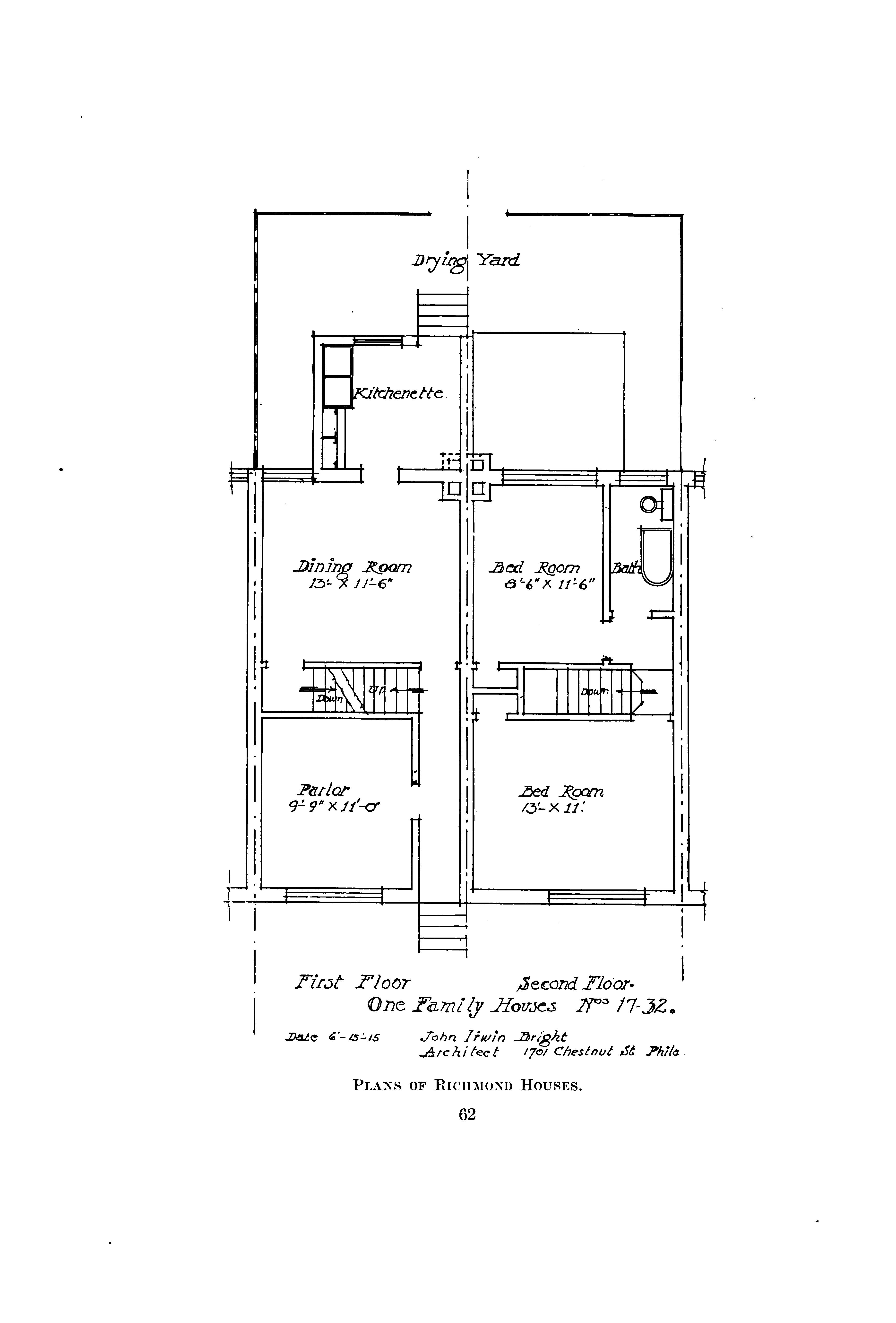

The Octavia Hill Association soon expanded its activities to other areas of the city, including Germantown, Kensington, and Manayunk. In 1915, a new division, the Philadelphia Model Homes Company, built a group of one- and two-family courtyard townhouses in Port Richmond. By 1929, the Association owned or managed a total of 450 housing units.

From its founding, the Association worked closely with settlement houses, the School of Social Work at the University of Pennsylvania, and the Philadelphia Housing Commission (later Association, then the Housing Association of the Delaware Valley), to pursue a common goal of improving living conditions in the city. Penn’s School of Social Work evolved out of the activities of reformer Mary Richmond (1861-1928), whose philosophy about friendly visiting greatly influenced Helen Parrish. Richmond’s view that friendly visiting provided reciprocal benefits to both middle-class friendly visitors and tenant families was the subject of her book The Good Neighbor in the Modern City, also published in a special Philadelphia edition.

Although mainly focused on day-to-day property management, the Association also commissioned Emily Wayland Dinwiddie (1879-1949) to study housing conditions in three South Philadelphia wards. Detailed information from this 1903 survey allowed Association members to move beyond friendly visiting and piecemeal reform to fight for effective housing legislation. One success was the Tenement Inspection Law of 1907.

The scope of the Association’s activities changed in the twentieth century as new legislation and agencies enforced stricter building codes, municipal services improved, Philadelphia established a Housing Commission, and the federal government became involved in public housing projects. The immigrant population also declined following passage of federal immigration restrictions in the 1920s. These factors, combined with problems meeting stockholder dividends, motivated a change in activities: after World War II, the Octavia Hill Association incorporated as a real estate management company that now manages both luxury and affordable housing in many areas of the city. In the last two decades of the twentieth century, the Octavia Hill Association built housing in North Philadelphia and Point Breeze, some for ownership rather than for rental.

Anne E. Krulikowski holds a Ph.D. in American history with a concentration in material culture/preservation from the University of Delaware. She teaches at West Chester University and the University of Delaware. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2012, Rutgers University.