Oh, Dem Golden Slippers

Essay

“Oh, Dem Golden Slippers,” the unofficial theme song of the Philadelphia Mummers Parade, is both an enduringly popular song and a revealing example of the complex, multilayered interplay between Black and white music in America. Written by African American songwriter James Bland (1854–1911) as a parody of a Negro spiritual, “Oh, Dem Golden Slippers,” published in 1879, enjoyed great popularity as a blackface minstrel song. It later became a staple of two very different, predominantly white, American musical traditions: bluegrass and the Philadelphia Mummers.

The story of “Oh, Dem Golden Slippers” begins with the Negro spiritual “Golden Slippers.” Negro spirituals were African American religious songs created in the pre-Civil War era by southern slaves. Part of an oral folk tradition originally practiced exclusively by and for Blacks, spirituals were brought to broader public attention in the 1870s by the Fisk Jubilee Singers, a Fisk University African American choral group that toured and concertized extensively in this period. The group presented Negro spirituals in more polished form, transformed from rough-hewn, improvisatory slave songs into formally arranged choral pieces. One of the spirituals they popularized in this fashion was “Golden Slippers,” a joyful song that described what the singers hoped to wear when they entered heaven: a long white robe, a starry crown, and golden slippers.

Meanwhile, another type of vernacular music with African American roots was enjoying great popularity: blackface minstrelsy. Minstrelsy grew out of white entertainers imitating Blacks with derogatory depictions of African American life and mannerisms. White entertainers would “black up” their faces with burnt cork and perform exaggerated songs and dances supposedly based on Black music and speech patterns. Such performances were common in the early nineteenth century, and by midcentury the minstrel show had evolved into a standardized, enormously popular form of theatrical entertainment. Philadelphia was an important center in the early development of minstrelsy and minstrel shows remained a popular form of entertainment in the city into the early twentieth century. Minstrel songs became part of the broader body of American popular song in the nineteenth century as well.

African Americans had occasionally performed as minstrels since the mid-nineteenth century, but in the years following the Civil War they began to enter minstrelsy in large numbers. With limited career opportunities otherwise in show business, many African American entertainers became minstrels, blacking up their own faces and performing the stereotypical portrayals of Black life their white counterparts had popularized. Thus evolved the ironic situation in late nineteenth-century American popular culture of Blacks imitating whites imitating Blacks. Some African American minstrels became famous in this period, especially James Bland, dubbed the “World’s Greatest Minstrel Man.”

Inspired by a Street Musician

James Bland was born in Flushing, New York, to a free, fairly well-to-do African American family. The family lived in Philadelphia for a while when James was young and it was here that he purportedly first fell in love with the banjo after hearing an elderly Black street musician playing one. After the Civil War the family moved to Washington, D.C., where James attended Howard University for a time before pursuing a career as an entertainer. In addition to enjoying great success as a minstrel performer, Bland was a prolific songwriter. Of the hundreds of songs he is reported to have written, only a few dozen have survived, including several that he wrote in a short creative burst in the late 1870s and early 1880s that were hit songs at the time and later became standards in American folk and popular music. These include “Carry Me Back to Old Virginny,” “In the Morning by the Bright Light,” and “Oh, Dem Golden Slippers.”

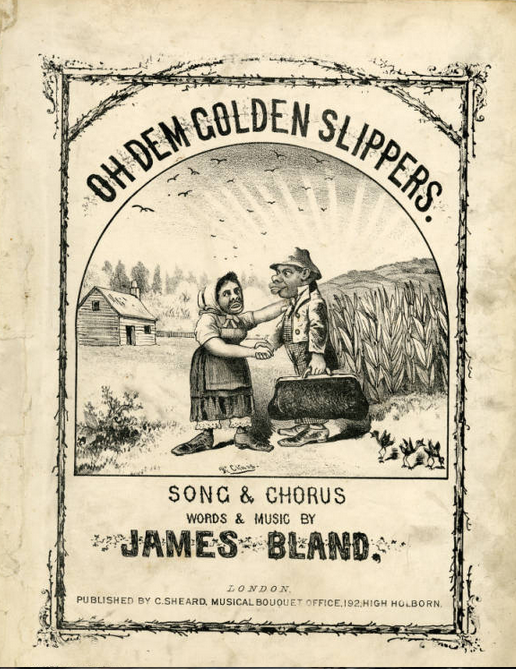

One of the hallmarks of minstrelsy was parody, satirizing the mannerisms and pretentions of others through song and dance. It was in this vein that Bland wrote “Oh, Dem Golden Slippers,” a parody of the spiritual “Golden Slippers.” “Oh, Dem Golden Slippers” was a lively dance tune with a stomping rhythm and a simple verse-chorus form. Lyrically, it used the same clothing imagery as the original spiritual, although with a less religious theme, and was squarely in the minstrel tradition, with comedic words in fractured “Negro dialect,” a defining feature of minstrelsy.

Tradition holds that local minstrel man Charles Dumont (1884–1959) introduced “Oh, Dem Golden Slippers” to the Philadelphia Mummers around 1905. Charles Dumont was the nephew of Frank Dumont (1848–1919), a well-known minstrel performer who operated minstrel theaters in Philadelphia in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. However, “Oh, Dem Golden Slippers” was a hit song in the 1880s and it may have been during this earlier period that it entered the repertoire of the Mummers, whose music was heavily influenced by minstrelsy and whose performances were largely based on parody.

The Mummers grew out of Christmas and New Year’s celebrations in Philadelphia dating back to colonial times in which various nationality groups observed the holidays by masquerading and reveling in the streets. These celebrations evolved over time into parades and other festivities with very elaborate costumes and unique styles of music and dancing. By the late nineteenth century, mummer celebrations had become quite large and raucous, particularly in South Philadelphia, the heart of the mummer tradition. In 1901 the City of Philadelphia established the annual New Year’s Day Mummers Parade, an organized parade up Broad Street featuring performances by various mummer clubs.

Golden Slippers on Their Feet

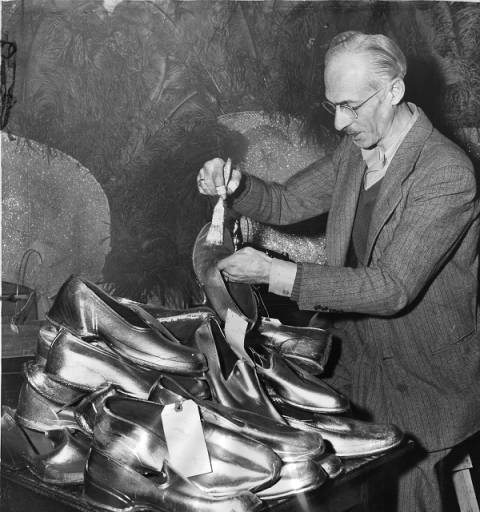

How and when “Oh, Dem Golden Slippers” became the unofficial theme song of the Mummers Parade is difficult to determine. (No song was ever officially designated as the Mummers theme.) By the early twentieth century it was a mainstay of the music of the New Year’s Parade and over time emerged as the song most closely identified with the Mummers, who even began a tradition of painting their shoes gold as part of their costumes.

Although its theme song was written by an African American, the Mummers Parade was largely an all-white event. A few Black clubs participated in the early twentieth century, but by the late 1920s they had dropped out due to the racially offensive nature of the performances, which continued to feature minstrel elements and often included provocative parodies of different ethnic groups. Blackface performers remained part of the parade until the 1960s. Efforts to make the parade more racially sensitive and diverse began in the late twentieth century and continued into the early twenty-first.

James Bland may have heard “Oh, Dem Golden Slippers” performed by Mummers towards the end of his life, when he lived in Philadelphia in the early 1900s. Bland had toured England in the early 1880s with Haverly’s Colored Minstrels, a prominent Black minstrel troupe. He remained there when the troupe returned home and enjoyed a very successful career as a celebrated minstrel performer in Europe. He moved back and forth between Europe and America in the 1890s before returning to the United States permanently in 1901. By this time Bland’s star had faded, as minstrelsy lost popularity to new forms of entertainment such as vaudeville and musical comedy. Philadelphia was among the major cities where minstrelsy remained fairly popular into the early twentieth century and Bland settled there hoping to find work. His career continued to decline, however, and he died forgotten and destitute in Philadelphia in 1911.

Several of Bland’s songs lived on long after his death. “Oh, Dem Golden Slippers” became a standard both in bluegrass, the rural string-based folk music of the Appalachian region, and in Philadelphia, where its role as the unofficial theme song of the Mummers Parade made it one of the most widely known songs in the city’s history.

Jack McCarthy is a music historian who regularly writes, lectures, and gives walking tours on Philadelphia music history. A certified archivist, he recently directed a major project for the Historical Society of Pennsylvania focusing on the archival collections of the region’s many small historical repositories. Jack serves as consulting archivist for the Philadelphia Orchestra and the Mann Music Center and worked on the 2014 radio documentary Going Black: The Legacy of Philly Soul Radio. He gave several presentations and helped produce the Historical Society of Pennsylvania’s 2016 Philadelphia music series, “Memories & Melodies.” (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Mummers' unofficial anthem composed by local black musician (WHYY, January 1, 2014)

- A kinder, gentler Mummers Parade appears to be in Philly's future (WHYY, January 1, 2014)

- Protestors try to interrupt Mummers Parade (WHYY, January 1, 2016)

- After sensitivity training, will Mummers rein in raucous antics? (WHYY, December 28, 2016)