Philadelphia Sketch Club

By Naomi Slipp | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

Founded in 1860, the Philadelphia Sketch Club became one of the oldest and longest continually operating American sketch clubs. Open to amateurs, students, and professionals, it became integral to Philadelphia’s artistic history. Initially founded as a weekly workshop by Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) students and alumni, who sought drawing training and criticism, the club began sponsoring exhibitions in 1865, awarding prizes and supporting an artists’ “relief fund.” The Sketch Club continued to sponsor exhibitions and workshops, remaining a vital artistic institution in the city.

In November 1860, sixteen PAFA students and alumni signed a charter for “The Crayon Sketch Club,” to support drawing and structured critique. Adopting the moniker “The Philadelphia Sketch Club” in 1861, their aim “was to stimulate creativity through regular meetings at which members would propose motifs or subjects … for general criticism” and operate the relief fund to support sick or impoverished artists and pay burial expenses. Members met weekly to sketch subjects decided by committee and submit monthly entries. Behavior and participation were policed and members were fined for swearing or failing to produce sketches. The club organized dinners and encouraged camaraderie among members, then limited to men.

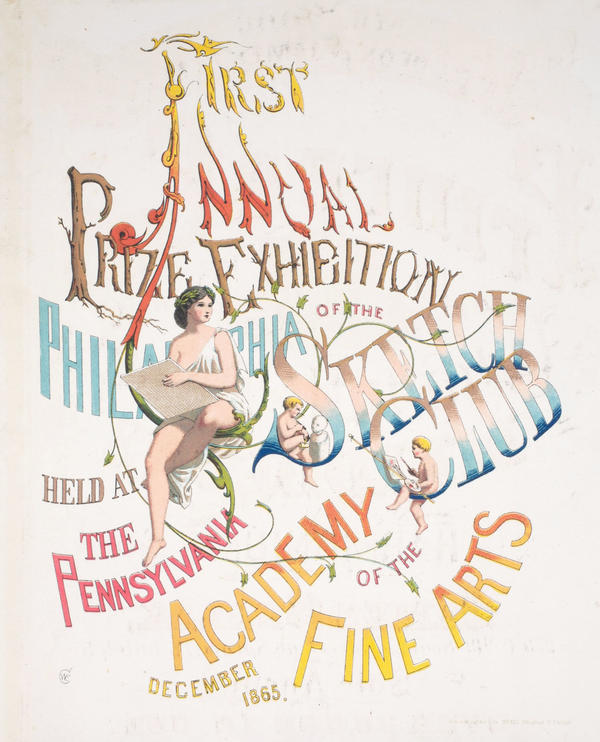

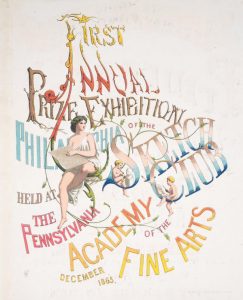

In December 1865, the club held its first Annual Exhibition at PAFA and offered a $2,000 cash prize for the “finest work illustrative of the great American Rebellion,” the American Civil War then in its final months. Philadelphia sculptor Howard Roberts (1843-1900) exhibited three sculptures alongside works by landscape painter Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902), portraitist G.P.A. Healey (1813-94), marine painter Edward Moran (1829-1901), Hudson River School artist Sanford Gifford (1823-80), and Italian expatriate Charles Caryl Coleman (1840-1928). The Philadelphia-based Evening Telegraph described it as the “most important display of … American works … ever made.”

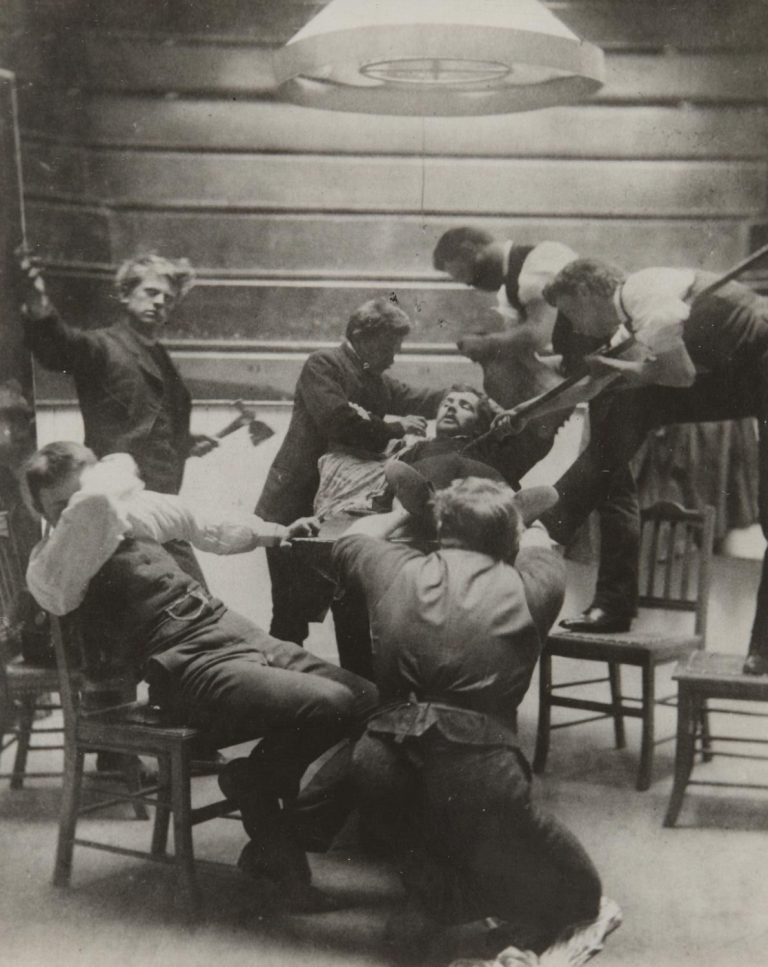

When PAFA sold its Chestnut Street location in 1870, commissioning a Frank Furness (1839-1912) building at Broad and Cherry Street that opened in 1876, Academy students and alumni utilized and animated the Sketch Club. In the winter of 1873, founding member and art critic Earl Shinn (1838-86) invited Thomas Eakins (1844-1916) to provide biweekly evening life-drawing classes for male members and nonmembers, which continued until 1876 when Eakins took an Academy assistantship. He also lectured on human anatomy and taught watercolor. Club enrollment increased. The club made Eakins a lifetime member, while students created a photographic parody of The Gross Clinic. In 1886, though, scandals surrounding Eakins’s instruction at PAFA and the club led Thomas Anshutz (1851-1912) to charge him with “conduct unworthy of a gentlemen and discreditable to this organization” and forced his expulsion from the club.

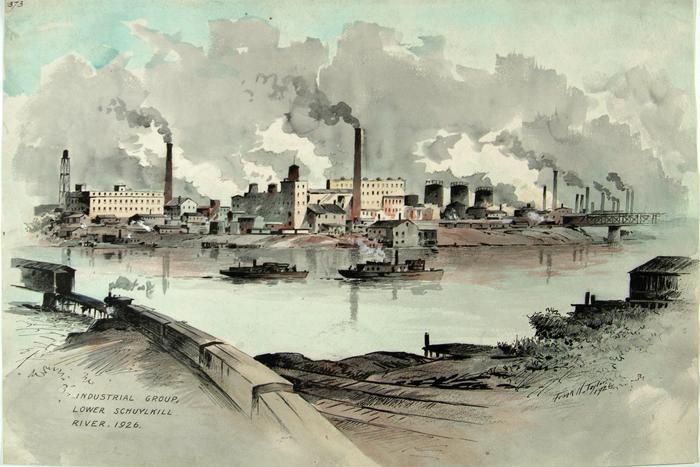

In 1874, club member and illustrator Frank Hamilton Taylor (1846-1927) published the “Philadelphia Sketch Club Portfolio,” replicating with photo-lithographs twenty-five original works by club members across twelve monthly volumes. The first folio included caricatures of eighteen members, such as Earl Shinn and Howard Roberts. As club president from 1873 to 1877, Roberts had a prominent role in planning the 1876 Centennial Exhibition, organizing the “Address to the Artists of the United States” at club headquarters and winning a medal for his sculpture Première Pose. The following year, Anshutz premiered his painting Ironworkers’ Noontime, judged an “outstanding work of the show.” Anshutz, who officially joined the Sketch Club in 1877, served as PAFA director in 1909 and Sketch Club president from 1910 to 1912.

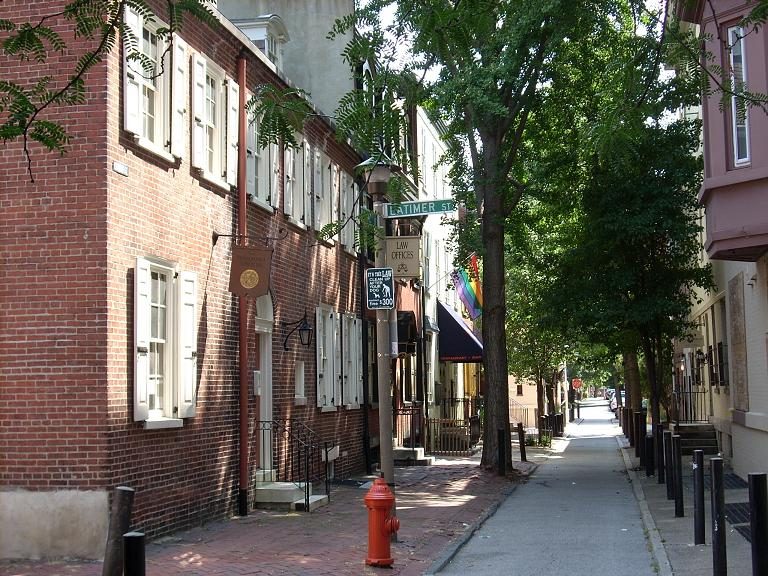

Throughout its early years, the Sketch Club occupied various temporary lodgings, including at 524 Walnut Street, No. 10 Northwest Penn Square, and 1328 Chestnut Street. In 1902, however, the club established a permanent headquarters by purchasing two adjacent row houses on Camac Street, adding a third in 1908. Following extensive renovations completed in 1915, the new headquarters included a skylighted gallery, meeting rooms, an archive, billiard room, library, gardens, sitting room, dining room, kitchen, etching room, and activity spaces, which served an expanded membership. Joseph Pennell (1857-1926), illustrator and president of the club in 1921, called Camac “The Little Street of Clubs,” also home to the women’s arts group The Plastic Club and the Franklin Inn Club. The Sketch Club’s headquarters, 235 S. Camac Street, gained listings on the Philadelphia and National Registers of Historic Places.

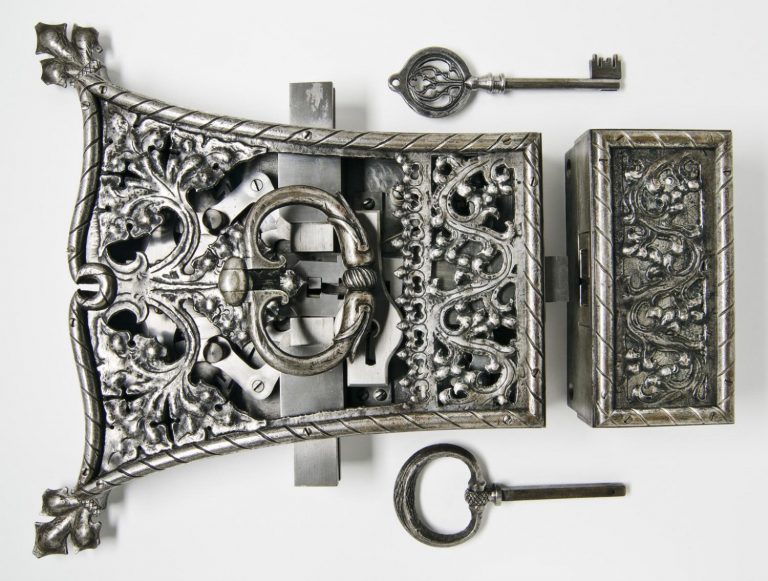

By the middle of the twentieth century, membership included a significant number of Pennsylvania Impressionists, master blacksmith Samuel Yellin (1884-1940) and renowned illustrator N.C. Wyeth (1882-1945). However, the club also limited the scope of participation. In an interview published in 2015 by the Woodmere Art Museum, painter Moe Brooker (b. 1940) recalled that artist Julius T. Bloch (1888-1966) boycotted Sketch Club exhibitions in the 1960s because the club refused to exhibit African American artists. Women artists, such as Violet Oakley (1874-1961) and Betty Bowes (1911-2007), exhibited with the club at the first exhibition and won prizes and medals; however, women were not allowed to become members until 1991, when the club became tax-exempt and had to comply with government mandates.

Although challenged by the proliferation of innovative galleries and more inclusive clubs and cooperatives founded since the 1970s, the Philadelphia Sketch Club remained an active part of Philadelphia’s artistic and cultural landscape in the early twenty-first century. By 2019, the Philadelphia Sketch Club retained approximately two hundred active members and ran public art workshops, sponsored exhibitions, and awarded competitive prizes and medals. These activities, and the club’s archive and art collection, including forty-four portraits by Anshutz of club members installed as a frieze in the library, have provided a vital link to Philadelphia’s cultural past and assured the club’s importance to Philadelphia’s art world.

Naomi Slipp is Assistant Professor of Art History at Auburn University in Montgomery, Alabama, has a Ph.D. from Boston University (2015), and publishes on Thomas Eakins, art and medicine, and the history of science. She worked at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 2005-8 and 2014-15.

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University