Plantations

Essay

When American patriots declared independence from Great Britain in 1776, the single largest boon to their cause was the nation’s ability to feed itself—as well as much of the Atlantic world. Beginning in the mid-1700s, crop failures across Europe and an expanding slave population in the West Indies created a huge demand for food from the colonies. Plantations and farms in the Mid-Atlantic region met this demand, producing vast amounts of flour, wheat, pork, and other foodstuffs to be shipped from the ports of Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore. In the process, plantation farming stimulated the development of the region’s transportation infrastructure and energized the already fierce dedication to scientific inquiry in the “City of Firsts,” Philadelphia.

In the aftermath of the Civil War, the word “plantation” became inextricably linked to slavery, but in the eighteenth century the word simply meant a property containing between one hundred and one thousand acres. In general, colonials referred to land with fewer than one hundred acres as a farm, and greater than one thousand acres as a manor. The average property in southeastern Pennsylvania in 1700 was six hundred acres, making most early tracts plantation-sized; by 1765 the average holding was still 135 acres.

In many ways, there were few differences between the smaller farms and the larger plantations. Both were family-run operations. Not until the 1820s did the first truly commercial farms come into existence. The landscape of both included a farmhouse, a springhouse for fresh water and storage of perishables like butter and milk, and a smokehouse for preserving meat during the fall butchering season. Most farms featured one or more barns for livestock (especially Pennsylvania’s signature “Sweitzer” barns built first by early German settlers), though through much of the eighteenth century farmers raised only as many animals as they absolutely needed. Native grasses were insufficient to graze large herds and the regular sowing of artificial grasses like timothy and clover did not occur until later in the century. Farms and plantations also featured a kitchen garden, which the women in the family managed for growing vegetables and herbs. In addition, farmers often maintained space for secondary occupations such as blacksmithing, tanning, and woodworking as a way of earning money during the off-season.

The High Cost of Labor

In the early colonial period the most limiting factor to farm production was not lack of land to clear, sow and harvest, but lack of hands to accomplish the work. Land was abundant and cheap. A wage laborer might quickly earn enough cash to become a farmer in his own right, and slaves and indentured servants could be prohibitively expensive. In the 1680s a prominent Quaker named Rowland Ellis (1650-1731) received 700 acres from William Penn (1644-1718) that he called “Bryn Mawr,” later known as Harriton. By the 1690s Ellis wrote to a relative that he had only fifteen acres under cultivation, barely enough to support his family. For specific tasks, the plantation owner might hire wage laborers who often “came to stay” for set periods of time. Many of these wage laborers were women (often extended family or near neighbors) who rendered domestic services like spinning, laundering, and butter-making in exchange for pay.

With so little help available, but with the abundant rainfall and temperate climate ideal for grain farming, the commonsense focus of the small farmer often fell to wheat. Wheat farming, characterized by bursts of intense labor interspersed with long periods of inactivity, only required an average of twenty-five working days per year to produce. By 1750 wheat was one of the most sought-after agricultural crops in the world. Between 1768 and 1772 the British North American colonies exported on average 1,989,000 barrels of flour and 599,000 bushels of wheat per year—much of it coming from the plantations and farms of southeastern Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey.

For farmers lucky enough to have many children or large extended families, or who could afford to purchase additional labor, the economic landscape was different. Larger-scale farming still centered on wheat and related grain crops, but more hands allowed farmers to diversify into crops like turnips, potatoes, flax, and tobacco, and to produce goods such as butter and cheese in quantities large enough to sell. With diversification came security against bad harvests or plummeting market prices, and for successful farmers who now had labor needs year-round, it made financial sense to invest in indentured servants and, to a lesser extent, slaves. In eastern Chester County, Pennsylvania, before 1700, for example, thirty-eight percent of households owned white indentured servants; from 1700 to 1760 the number ranged from fifteen to twenty-two percent. While ownership of indentured servants decreased after the mid-1700s—due in part to the disruption in immigration caused by the Seven Years’ War—the ownership of slaves in the liberty-loving Quaker colony increased, especially from 1750 to 1780 when grain and flour exports were at their peak. In the 1770s nineteen percent of households in eastern Chester County held slaves, especially farmers who also engaged in milling, tanning, or some other trade that generated more work than the family could accomplish alone.

Agriculture’s Larger Influences

The success of the Delaware Valley’s plantation economy not only stimulated a global trade, but also contributed to domestic improvements. Getting wheat, potatoes, linseed oil, salted pork, and other items to Philadelphia or Wilmington over coarse dirt roadways proved costly and dangerous. Under the best of circumstances a team of oxen took three days to haul grain just twenty five miles. Farmers in Lancaster County and westward often found it cheaper to float their produce down the Susquehanna River to the Chesapeake Bay. This profit loss spurred Philadelphia merchants to support a new toll-based system of paved turnpikes connecting the fertile fields of Lancaster with the bustling markets along the Delaware River.

By 1790, the “best poor man’s country” had begun to show its age. The challenges of new diseases, invasive pests, and the declining fertility of overworked land led to an active regiment of “gentlemen farmers” whose fortunes allowed them to experiment with new techniques with which working farmers could not afford to gamble. These men promoted the use of clover in crop rotations to increase soil fertility, and devised ways to combat the Hessian fly, a pest wreaking havoc with wheat crops. The North American Hessian fly infestation began in the late 1770s in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut; by 1786 it crossed into southeastern Pennsylvania, and by 1792 it devastated the rich wheat fields of Delaware and northern Maryland.

Former Chief Justice Benjamin Chew (1722-1810) of Philadelphia tested the theories of agricultural reformers for fighting the Hessian fly at his nearly 1,000-acre Whitehall Plantation in Kent County, Delaware, after his wheat yields plummeted from 1,145 bushels in 1792 to a crippling 205 bushels in 1793. Chew responded to this disaster by sowing his wheat later in the season, since the Hessian fly thrived in the warmer and more humid temperatures found in early fall. He also used the new yellow bearded variety of wheat, whose bristled heads seemed better equipped to fend off the insects. Seeking reliable alternatives to wheat, Chew planted as many as 150 acres of corn, as well as barley and rye. By 1800 Chew’s wheat yields had returned to nearly pre-fly levels, but by that time corn had also found a lucrative foothold in the markets of Europe and the Caribbean.

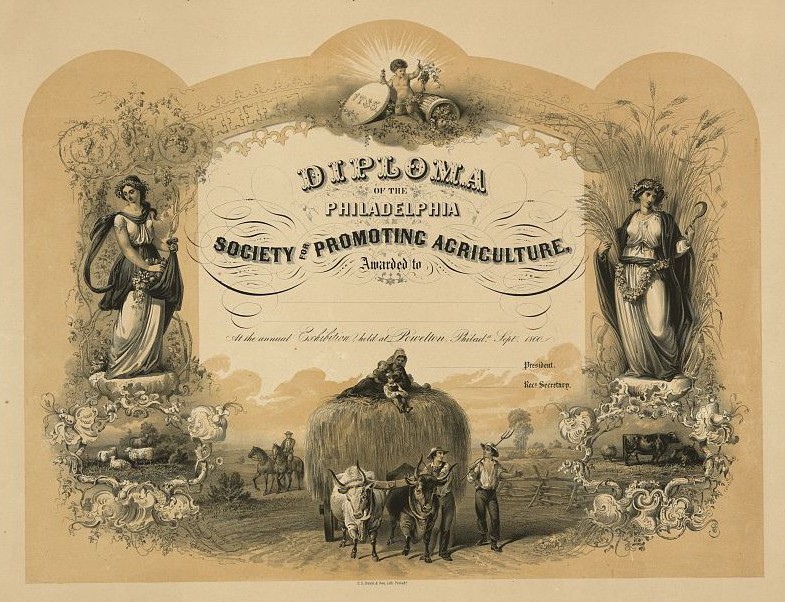

The last two decades of the eighteenth century emerged as a period of incredible agricultural and economic changes. Not only did the Hessian fly topple wheat from its place of honor as the centerpiece of a complex trans-Atlantic trade system, but a revolution in agricultural thought and practice—virtually unchanged for hundreds of years—was underway. In 1785 John Beale Bordley (1727-1804) of Como Farm in Chester County, and Charles Thomson (1729-1824) of Harriton in Montgomery County spearheaded the Philadelphia Society for Promoting Agriculture, an organization dedicated to improving farming methods and agricultural education. From scientific study of weather to practical experimentation with new tools and machinery, the PSPA challenged many long-held beliefs and farming traditions. Their robust support of the use of fertilizers like gypsum and lime made possible the systemic planting of nonnative grasses like clover, timothy, and alfalfa, which in turn allowed farmers to feed more livestock. As a result, from 1790 to 1840 agriculture gradually shifted away from grain-based farming and toward the dairy farms that made nineteenth-century Philadelphia famous for its butter and cheese. The early nineteenth century also brought the continuing division of plantations through the generations. Where the average property in the mid-1700s was over one hundred acres, by the mid-1800s plantations were less the norm, and more the anomaly.

Jennifer L. Green is Director of Education for the Colonial Pennsylvania Plantation, an eighteenth- century living history farm in Media, Pennsylvania. She has previously worked at The Mill at Anselma, a colonial-era grist mill in Chester County, where her study of early American agricultural and industrial history began. In addition to the Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, she has written multiple articles for ExplorePAHistory.

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University