Philadelphia Police Department

By Alex Elkins

Essay

Created by state law in 1854 to maintain public order, prevent riots, and apprehend criminals, the Philadelphia Police Department operated for its first hundred years under direct control of politicians and served the reigning party’s interests by collecting graft as well as apprehending vagrants and solving crimes. During the twentieth century, especially in the latter decades, reformers sought to retool the force to align it with constitutional law and democratic norms. While this resulted in a more professional ethos of public service and crime prevention, the department continued to struggle with corruption and racism as it engaged in a vigorous war on crime.

Policing Philadelphia began in the seventeenth century with constables appointed by English colonial authorities. Early constables enforced magistrate decisions and closely regulated working-class leisure activities like “cards, dice…revels, bull-baitings, cock-fightings,” as one 1681 English law put it. That year, William Penn (1644-1718) gained his charter for Pennsylvania, including the 35-acre tract that became the city of Philadelphia, bounded by the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers and north and south boundaries that became Vine and South Streets. Penn appointed a sheriff to ensure a “well-regulated” population.

In July 1700, the Common Council established the night watch, a person who carried a bell to alert the constable about criminal activity. Constables and the night watch investigated vagrants and “disorderly persons” and regulated the hours of public houses to prevent drunken fights and riots. In 1751, Council added a Board of Wardens responsible for “well-ordering and regulating the Watch” and maintaining a sufficient number of lamps in their wards. This 1751 ordinance also paid constables and night watchmen their first wages. In 1810, the city had 1,132 lamps and fourteen constables. Twenty years later, the entire city watch consisted of 106 men. Due to a large bequest of wealthy merchant Stephen Girard (1750-1831), the watch expanded to twenty-four day police and 120 night watchmen.

Growing Conflicts in a Growing City

In Philadelphia County, including the city, the early industrial era severely tested the fragmented, overstretched, and largely voluntary policing system. In the 1830s and 1840s, native-born Protestants clashed with newly arrived Irish Catholic immigrants over jobs, the use of Bibles in school, alcohol, and political office. In 1838, the same year a new Pennsylvania constitution disenfranchised blacks, white rioters burned down the abolitionist meeting place Pennsylvania Hall soon after its opening.

Cosmopolitan elites saw communal riots as evidence of deficiencies in decentralized government. As part of their plan to merge city and suburbs, they proposed a countywide police force to discipline the turbulent industrial workforce. Consolidation advocates won an important victory on May 3, 1850, when the state legislature established the elective office of county police marshal, created four countywide police divisions (each commanded by a lieutenant), and raised police strength to a maximum of one officer per 150 taxable inhabitants, thereby committing the county to maintaining a police force through its tax base. The 1850 law also granted the police marshal executive authority to declare a state of emergency during disorders. Future mayors seized upon this statutory authority to impose “riot curfews” restricting citizens’ use of the streets during unrest.

In 1854 the Act of Consolidation, which united city and county under a single government, created the Philadelphia Police Department to oversee a greatly expanded jurisdiction encompassing 129½ square miles and roughly 500,000 inhabitants. The law raised the potential size of the force to 820 patrolmen and established tiered salaries according to rank. The new police wore uniforms, which clarified the distinction between citizen and state, a line frequently blurred in the previous semiprivate system. It was an important step toward professionalization.

However, the 1854 law also ensured political dominance of the police. It established coterminous boundaries for the districts and wards. The mayor had the power to appoint one lieutenant and two sergeants per district and could give them direct orders. Aldermen, appointed by City Council, also served as magistrates, who, with a police official (also a political appointee), adjudicated criminal trials in the station houses. This system lasted with minor variation for about a century. Even when the city introduced civil service exams in 1885, patronage, not merit, continued to dominate major police decisions of personnel and policy.

A New Police Role: Prevention

In 1856, Mayor Robert T. Conrad (1810-56) described the purpose of the new Police Department as “prevention.” Rather than wait “patiently until crime was committed,” the police would commit to “overspreading and guarding the whole community.” Philadelphia police focused mainly on public-order offenses like drunkenness and vagrancy. Most street policing was done by officers walking the beat. In 1889, the department purchased ninety-three horses to supplement foot patrol. Sixty years later, the force switched to automobiles.

The department’s stance on race and ethnicity also changed over time. In the mid-1850s, when nativist politicians controlled city government, native birth was a condition of employment for police. Nativism proved short-lived, but the prejudice held. It was not until the turn of the century, when one out of every four city residents was foreign-born, that the department began hiring Irish and Italian immigrants. In 1884, Mayor Samuel G. King (1816-99) appointed the first black officer; by 1896, the force had sixty black officers, assigned mainly to predominantly black neighborhoods. However, whites dominated the force until the 1970s, and they used their power to harass racial minorities. A 1926 study found that police considered African Americans “easy prey” for illegal arrests. A survey from 1952 showed a similar pattern of police misconduct and harassment against African Americans and mixed-race social gatherings.

Between 1870 and 1910, the city’s dominant Republican Party used the Police Department to cement its political machine, strengthen its hold on the polls, and maintain profitable contacts with the criminal underworld, especially the vice syndicates in gambling and prostitution. Typically, a ward leader sponsored an applicant for a police job. As an officer, he often would collect payola, or protection money, from a vice operator and send it up the chain of party command. The famous muckraker Lincoln Steffens (1866-1936) was thinking in part of the police when he declared Philadelphia “the most corrupt and the most contented” city in the country in 1903.

The administration of Progressive Mayor Rudolph Blankenburg (1843-1918), from 1911 to 1915, was the first to try to reform the Police Department along professional standards. The department introduced a new patrol manual, the first since 1897, barred police from participating in politics while on duty, and revamped the annual reports from impressionistic, anecdotal accounts to empirical analyses of crime statistics. The return of machine rule after 1915, however, reversed many of these reforms.

Prohibition’s Challenges

During Prohibition, Mayor W. Freeland Kendrick (1874-1953) appointed Marine general Smedley D. Butler (1881-1940) as director of public safety to enforce the federal anti-liquor law. Butler organized the Motor Bandit Patrol for high-speed pursuits, dissolved the School of Instruction (police academy) to put more officers on the beat, and authorized get-tough illegal tactics to make hundreds of arrests, few of which were sustained in court. “Raid and keep on raiding,” Butler liked to say. After two years, in 1926, Butler left Philadelphia as he had found it, a “wet city.” Butler also failed to abolish graft. Two grand juries, in 1928 and 1937, uncovered extensive corruption on the force; in 1937, fifty-two officers and the mayor were indicted.

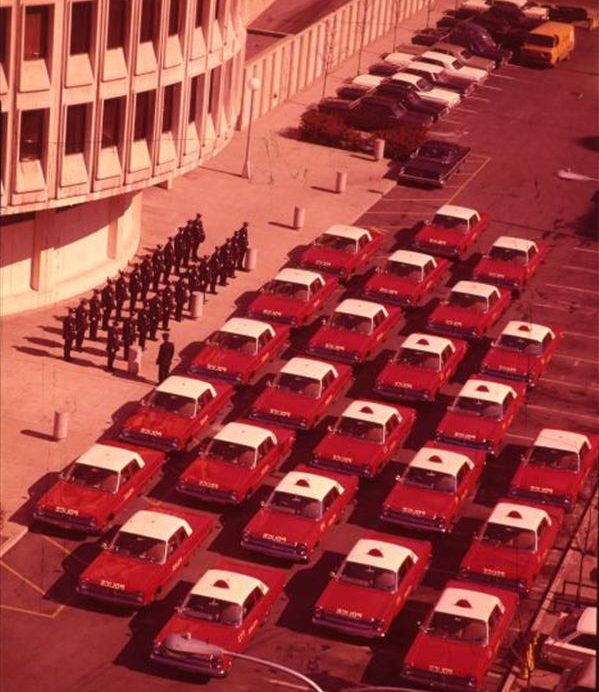

In the 1930s the Police Department introduced red squad cars (shifting to blue-and-white in the 1970s). The cars had two-way radios, allowing patrol officers to communicate with dispatch and command to enforce work discipline. In 1939, in response to city pay cuts during the Great Depression, the rank-and-file unionized and set up Lodge #5 of the Fraternal Order of Police. In 1950 the FOP and the city agreed to an exclusive collective-bargaining arrangement. Eighteen years later state legislators enshrined this right in law. The law barred the FOP from striking, but contract disputes could be resolved through binding arbitration.

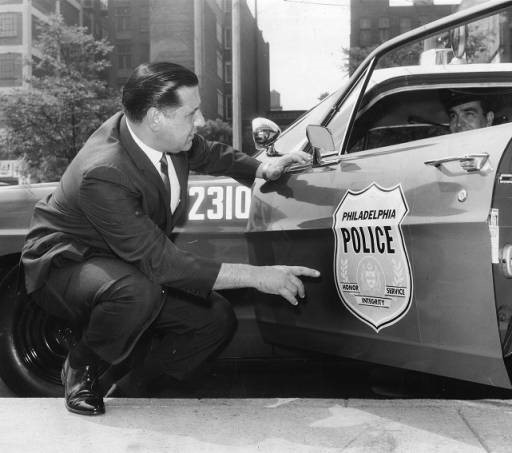

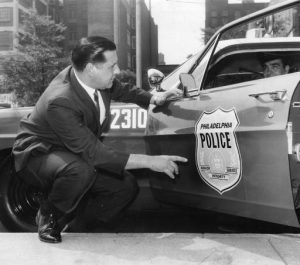

A wave of reform in city government in the late 1940s and early 1950s brought new scrutiny and change to the Police Department. In 1948 a public investigation disclosed widespread corruption, particularly the detective and vice bureaus, tied to illegal gambling. Three years later, voters ratified a new Home Rule Charter, which included provisions to isolate police from political influence. Democratic Mayor Joseph S. Clark Jr. (1901-90) selected Thomas J. Gibbons (1904-88) as the first police commissioner in the new system. Gibbons consolidated the police districts and redrew their boundaries to separate them from ward lines. He relocated hundreds of patrolmen out of their home neighborhoods and abolished the corrupt Vice Squad. Gibbons introduced study and planning to police operations to augment motorized patrols.

The department opened the Home Rule era with a crackdown on vice and small-time street disorder. Local police led dozens of raids in coordination with federal agents to enforce a federal anti-narcotics law passed in 1952. Police mainly targeted low-level pushers and users in the predominantly poor and black neighborhoods of South and North Philadelphia. As the Clark administration, backed by the wealthy investors who had led the Home Rule campaign, launched ambitious downtown renewal plans to clear blighted areas, the Police Department did its part by waging an aggressive campaign against the homeless in downtown areas.

Police-Community Partnership

Gibbons tried to win support for aggressive street policing through partnerships with middle-class representatives of the black community. In the late 1950s, the Police Department became one of the first in the country to organize regular precinct meetings in black neighborhoods to improve police-community relations. The department also introduced training in civil rights and constitutional law. Yet, the force was more than 95 percent white. A survey in 1957 found that most white officers believed African Americans were predisposed to crime. Of the thirty-two people shot and killed by police between 1950 and 1960, twenty-eight—87.5 percent—were black, even though blacks made up 22 percent of the city population.

Moreover, Gibbons’s own aggressive tactics undercut his progressive policies. In black neighborhoods the department fielded “shotgun squads” of officers patrolling in cars with sawed-off shotguns leaning out the windows in a show of force. After sensationalized attacks upon white women or gang violence, Gibbons ordered mass arrests of hundreds of young black men. In its war on gambling, the Police Department conducted illegal home raids on middle-class black residents. In October 1958, after public outcry led to City Council hearings, Mayor Richardson Dilworth (1898-1974) appointed the country’s first civilian review board to investigate complaints of police conduct. However, the FOP obtained two court injunctions that shut down the operations of the board, which was abolished in 1969 by Democratic Mayor James H. J. Tate (1910-83).

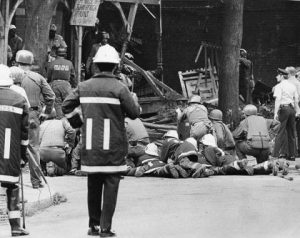

Tensions between get-tough and progressive police policies were on display during the three-day Columbia Avenue Riot in North Philadelphia in August 1964. Typical of much urban unrest in the sixties, a scuffle with police during a routine arrest touched off days of rioting, looting, and violence. Police Commissioner Howard Leary (1911-94), an advocate of constitutional law enforcement and a supporter of civilian review boards, instructed police to contain the area and use minimal force. Leary’s riot control plan won widespread praise outside the department, especially from local black activists, but it embittered the largely white rank-and-file, who felt powerless and humiliated.

The disgruntled rank-and-file found a champion in Deputy Commissioner Frank L. Rizzo (1920-91), who fought with Leary during the riot over his strict controls on firearms use. A national voice of get-tough policing as commissioner (1967-71) and mayor (1972-80), Rizzo declared war on the city’s dissident groups, especially Black Power militants. Notoriously, in August 1970, following the murder of a Fairmount Park police officer, Rizzo’s police raided the Black Panther Party offices and strip-searched members in front of news photographers.

Court Rulings Target Police Tactics

For this and similar “tough” actions against hippies, homosexuals, and antiwar protesters, Rizzo and the Police Department were the subject of multiple federal lawsuits. Federal court rulings in the 1970s and a 1973 state law restricting use of police force against “fleeing felons” greatly reduced the incidence of police shootings. In 1974, for example, the peak year under Rizzo, police shot ninety-seven suspects and killed thirty-one. By the mid-1980s, despite high levels of violent crime, annual police shootings were consistently lower than thirty and killings less than ten.

After the changes to civil service rules under Home Rule, corruption continued to be a serious problem but shifted from tribute paid to machine politicians to extortion of low-level participants in the vice trades. In 1974 the Pennsylvania Crime Commission found it to be “ongoing, widespread, systematic, and occurring at all levels of the Police Department,” especially in narcotics work. In the late 1980s and mid-1990s, city and federal officials accused narcotics officers in the Thirty-Ninth District of systematically robbing, beating, and framing suspects in drug cases. Altogether, ten officers went to prison. The city overturned five hundred convictions and paid more than $4 million to settle civil rights lawsuits.

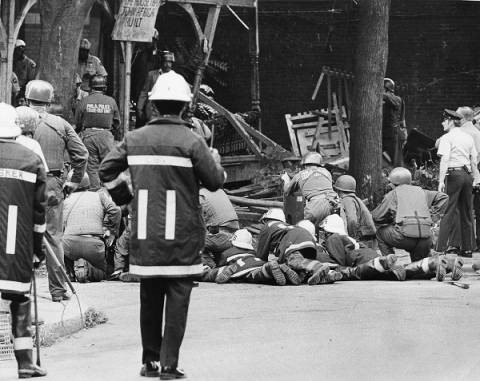

The damage of Rizzo’s policies on relations between the Police Department and black residents continued long after he was out of office. In 1978, police laid siege to the headquarters of the black liberation group known as MOVE in Powelton Village to enforce a court-ordered eviction. The ensuing shootout killed one police officer and injured several officers and MOVE members. On May 13, 1985, W. Wilson Goode (b. 1938), Philadelphia’s first black mayor, approved a police order to drop a bomb on a fortified West Philadelphia row house in which MOVE members had barricaded themselves. The bombing killed eleven people, including five children, and destroyed sixty-one homes.

After contentious public hearings on the MOVE bombing, Goode offered a formal apology and appointed Kevin M. Tucker (1940-2012) as police commissioner to reform the department. Tucker moved to implement the protocols of community policing, including more foot patrols, neighborhood advisory councils, and mini-stations, and expanded human relations training. Tucker’s successor, Willie Williams (1943-2016), Philadelphia’s first black commissioner, extended these reforms.

A White Male Institution

Nevertheless, the department remained a predominantly white male institution. Three times between 1974 and 1983 a federal court found the department in violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which forbid racial and gender discrimination in hiring, and imposed consent decrees with quotas for hiring women, African Americans, and Hispanics. As a result, in 1976 the department opened the Police Academy to women. By 2015 women, African Americans, and Latinos made up roughly 25 percent, 34 percent, and 8 percent of the force, respectively, in a city that was 44 percent black and 13 percent Latino.

Despite gains in diversity, the Police Department continued to face allegations of brutality from residents of color. In 1996 the American Civil Liberties Union, the NAACP, and the Police-Barrio Relations Project sued the department in federal court, alleging corruption, excessive force, and racial discrimination. The city settled, and Democratic Mayor Edward G. Rendell (b. 1944) created the Integrity and Accountability Office and set up a task force to investigate corruption, while the department introduced new reporting requirements for use of force. Two years later the department consolidated the separate internal affairs units under a single inspector.

In 1998, Rendell appointed John F. Timoney (1948-2016) as police commissioner. Timoney, second-ranked under William Bratton (b. 1947) in the New York Police Department, brought his former boss’s “broken windows” strategy, which focused on suppressing low-level street disorder to prevent more serious crime. Timoney and Bratton represented a new wave of police reformers who favored proactive methods such as the aggressive patrol technique of stop-and-frisk. Citing New York’s recent massive decline in violent crime, in Philadelphia Timoney also implemented CompStat, a computer program to gather real-time data about arrests and complaints and assign patrols based on neighborhood crime trends.

Timoney’s successors continued aggressive proactive policing. In the 2000s, the department launched massive operations to retake drug corners, resulting in tens of thousands of arrests. Philadelphia had 406 homicides in 2006, the highest rate among big cities, leading Mayor Michael Nutter (b. 1957) to declare a “crime emergency” after he took office in 2008. His police commissioner, Charles H. Ramsey (b. 1950), ordered an aggressive stop-and-frisk program in predominantly black districts. In 2009 the Police Department, in partnership with criminologists at Temple University, used foot patrols targeted to crime “hot-spots.” Researchers claimed that focused deterrence, as the strategy was called, reduced violent crime by as much as 20 percent. Two years later, the city’s homicide rate reached its lowest point since 1967.

High Price of Stop-and-Frisk

Such police tactics, however, reignited tensions between residents of color and the Police Department. Between 2009 and 2013, the city agreed to settlements totaling more than $45 million with plaintiffs alleging civil rights violations, including a federal lawsuit over Ramsey’s stop-and-frisk policy. In March 2015, the Department of Justice criticized the Police Department for “lack of transparency” in use-of-force cases. In the same month, a judge reversed 110 drug convictions—450 in the preceding year and a half. The Inquirer called it the “biggest single-day action in the city’s history of police scandals.” In the fall of 2015, Nutter requested $500,000 to equip 450 officers with body-worn cameras, to increase police accountability and community trust in street interactions. Ironically, while federal courts ruled on allegations of excessive use of force, the Police Department also received military gear and weapons from the federal government through a program to distribute surplus equipment to assist in the war on drugs.

In the mid-2010s the Police Department came under heavy criticism from black activists and residents for its aggressive tactics and lack of accountability, the latter due in large part to the generous civil service protections won by the unionized rank-and-file. Meanwhile, the department faced unrelenting pressure to stop crime from city officials, advocates of downtown growth, and residents of color in high-crime areas. After fifty years of white suburban flight, the loss of manufacturing jobs, and anemic revenue, the city increasingly relied upon its police force, the fourth-largest in the country, to manage the social consequences of urban decline. Despite new high-tech instruments of crime prevention and an expanding thicket of administrative and statutory regulations, the Police Department thus retained its founding role as the city’s peacekeeping force.

Alex Elkins is a Ph.D. Candidate at Temple University, where he is writing a history dissertation on post-World War II rioting and policing in the United States. He recently published “Stand Our Ground: The Street Justice of Urban American Riots, 1900-1968,” a review of five riot books, in the Journal of Urban History (March 2016).

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Police Department announces launch of surveillance camera-sharing program (WHYY, August 1, 2011)

- Advances in crimefighting, medicine, policy help reduce Philly homicide rate (WHYY, January 3, 2014)

- Philly police set to test out wearable cameras (WHYY, November 25, 2014)

- Community Policing 101: A safer neighborhood requires neighbor involvement (WHYY, November 10, 2015)

- LGBT police officers in Philadelphia area form chapter of GOAL (WHYY, November 27, 2015)

- Ross becomes Philadelphia police leader (WHYY, January 5, 2016)

- Philly police could headline at former Inquirer building (WHYY, May 31, 2016)

- Shining the light on police corruption in Philadelphia through transparency (WHYY, November 28, 2016)

- Historical marker coming to site of MOVE debacle (WHYY, March 31, 2017)

- Philly police headquarters moving to former Inquirer building on North Broad (NewsWorks, May 24, 2017)

Links

Connecting the Past with the Present, Building Community, Creating a Legacy