Privateering

Essay

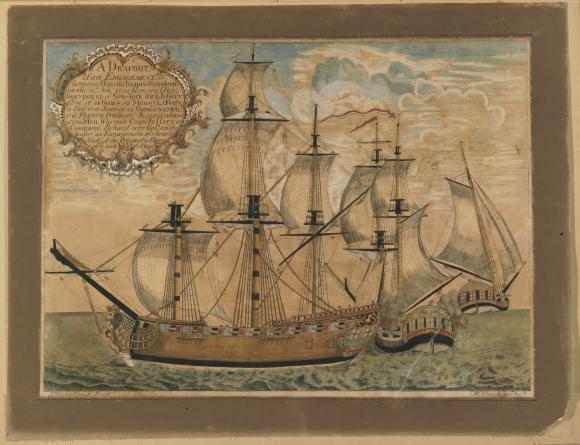

As one of the largest British ports in North America, during the eighteenth century Philadelphia held a prominent place in privateering, the practice of privately financed warships attacking enemy shipping during wartime. These vessels, either converted merchant vessels or purpose-built commerce raiders, were often investments of wealthy or enterprising merchants.

In order to operate legally, a privateer had to carry a letter of marque. This document separated a privateer from a pirate by granting the vessel governmental authority to raid opposing vessels. Privateers could either seek out enemy shipping lanes in order to locate and target enemy ships or simply haul cargo and if necessary attack and capture enemy vessels.

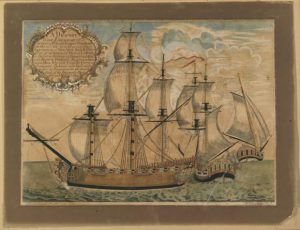

Privateers sought to inflict minimal damage on targeted vessels. Prizes, or captured enemy vessels, were only valuable if they survived a battle, and sunken ships could only be salvaged in the shallowest waters. Privateers would either bombard an enemy ship until its captain ordered surrender or attempt to close the distance in order to grapple and board the vessel. Once an enemy ship was captured, the privateer would send some of its crew along with a junior officer to act as a “prize crew.”

As an extension of naval efforts, privateering in North America generally occurred during wartime. The most active periods during the colonial era were therefore the War of Jenkins’ Ear, a colorful name for a war between Great Britain and Spain originating from British merchant captain Robert Jenkins, whose ear Spanish captors severed as punishment for smuggling, also known as King George’s War between Great Britain and France (1739-48); the Seven Years’ War (1756-63); and the American Revolution (1776-83). During the 1740s, privateers captured 69 percent of all prizes among British colonial vessels. Around that time, Philadelphia operated an average of forty-seven privateers annually, or about 10 percent of the total in the colonies. Philadelphia privateers remained active throughout the Seven Years’ War, with a number of prominent captains claiming lucrative prizes. During the American Revolution, Philadelphia was again one of the more important privateering cities, hosting 283 vessels out of 1,151.

Caribbean: Privateering Hotspot

Operating areas for privateers could cover a wide geographic range, but statistics show an obvious preference for the Caribbean. In the 1740s, nearly 90 percent of all prizes were taken there. Cuba and Hispaniola received the most attention, with eastern Caribbean islands following closely behind. Of the remaining 10 percent of cruises occurring farther north, nearly half were around the Newfoundland Banks and just over 20 percent off the Carolina Coast, followed by Cape Breton, Florida, and New England.

Prizes were often brought to friendly ports, preferably the privateer’s home port, where the captors filed official requests with the vice-admiralty court to condemn vessels’ legal prizes. Other claimants could then dispute the request. If condemned, the prize and its goods could be disposed of as the privateer’s owner saw fit. After paying often-exorbitant legal fees (colonial courts were notorious for charging far more than the “official” limit of £15), remaining prize money went to the investors, with portions distributed among the officers and crew. Privateer crews usually received their portions of the profit at the ends of their cruises. A successful cruise could earn even the lowest-ranking sailors small fortunes, which gave rise to the prevalence of willing sailors. The opportunity to “get rich quick” even attracted some potential sailors from wealthy backgrounds.

Some prizes were ransomed rather than captured. Admiralty courts required commanders to submit documentation and subject themselves to examination by court officials. Because this process could be difficult, prizes were often released after their captains agreed to pay ransoms. Captains from the two vessels would agree upon a price, and an officer from the captured ship would be taken as a sort of hostage. Paying a ransom was generally much cheaper than losing a vessel, so owners often ordered their captains to ransom their vessels if captured. Ransoms could also be accepted if taking the prize to a friendly port was not feasible. Sometimes the risk of safely carrying a prize back to friendly territory was too great.

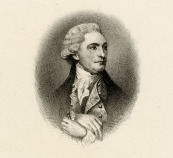

Privateering could earn practitioners great fortunes. John McPherson (1726-92), a successful Philadelphia merchant, gathered wealth sufficient to build the estate Mount Pleasant. That estate was later sold to Benedict Arnold (1741-1801) and survived as a prominent structure in Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park. William Bingham (1752-1804), a Pennsylvania delegate to the Continental Congress and later United States senator, began his fortune with money earned from operating the privateer Reprisal, which fought off a British sloop during the American Revolution and then successfully delivered war-related goods to Congress in Philadelphia.

A Dangerous Occupation

Though potentially lucrative, privateering was also dangerous. Though McPherson earned a fortune, he came close to losing his life in a battle with a French frigate in 1758. He managed to escape with the losses of an arm and over a quarter of his crew. Other Philadelphia privateers engaged in battle with enemy privateers and naval vessels. Some were captured or destroyed, some suffered significant damage, and others had to drop their cargo in order to gain speed and flee stronger vessels.

Privateering continued beyond the American Revolution. A number of privateers operated out of American ports during the War of 1812, though a far smaller portion came from Philadelphia than in previous wars. The practice largely disappeared from the western world after European powers signed the Paris Declaration Respecting Maritime Law of 1856, which officially abolished privateering. The Confederacy employed privateers in the early part of the United States Civil War, but the practice was short-lived. The United States abided by the Paris Declaration’s principles beginning in 1861.

Though the practice was eventually discontinued, privateering was a significant activity in colonial Philadelphia. Privateers operating out of the city contributed to the greater British war efforts against the French while Philadelphia merchants at times suffered at the hands of enemy privateers. Because it was such a large and influential port, many prizes were brought to Philadelphia and condemned in its vice-admiralty court. While few privateer captains and investors truly made fortunes from the practice, privateering directly or indirectly impacted the lives of a substantial portion of Philadelphia’s citizenry.

Matthew J. Wayman is Head Librarian at the Ciletti Memorial Library, Penn State Schuylkill, and a military historian. He received his M.L S. from Rutgers University and his M.A. in History from Temple University.

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Privateers of the American Revolution (National Park Service)

- A History of American Privateers (Archive.org)

- Traitor's Nest: Mount Pleasant (PhillyHistory Blog)

- Mount Pleasant, Historic Houses (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

- A Spanish Privateer on the Delaware (1748) (Sam Houston State University)

- Cruising for dollars: Privateers in the world of 1812 (National Parks Service)

- The War of 1812: Privateers, Plunder, & Profiteering (The Text Message Blog, National Archives)