Seventh-day Adventists

By Emily Bailey

Essay

Seventh-day Adventism, one among several uniquely American-born Christian traditions, resulted from the religious fervor and innovations of the Second Great Awakening (c. 1795-1830), which generated schisms in established churches and plantings of new religious associations across the United States, including Philadelphia and the Delaware Valley region.

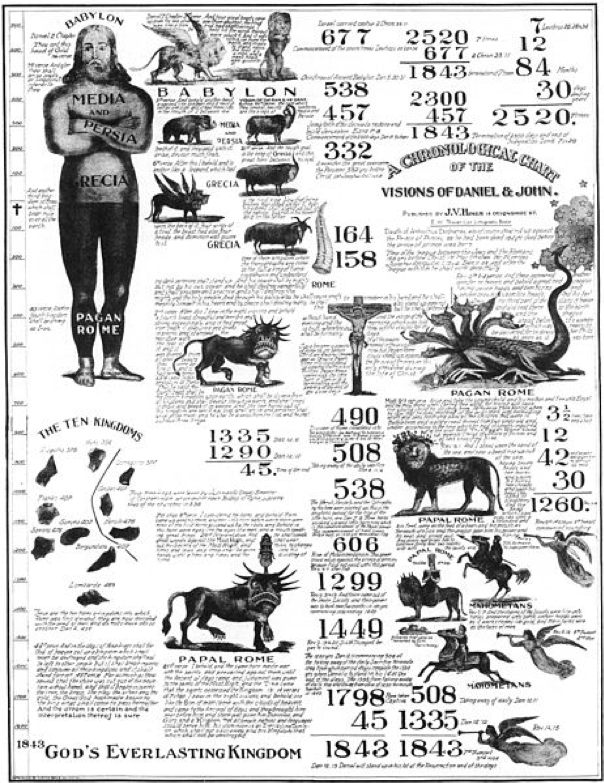

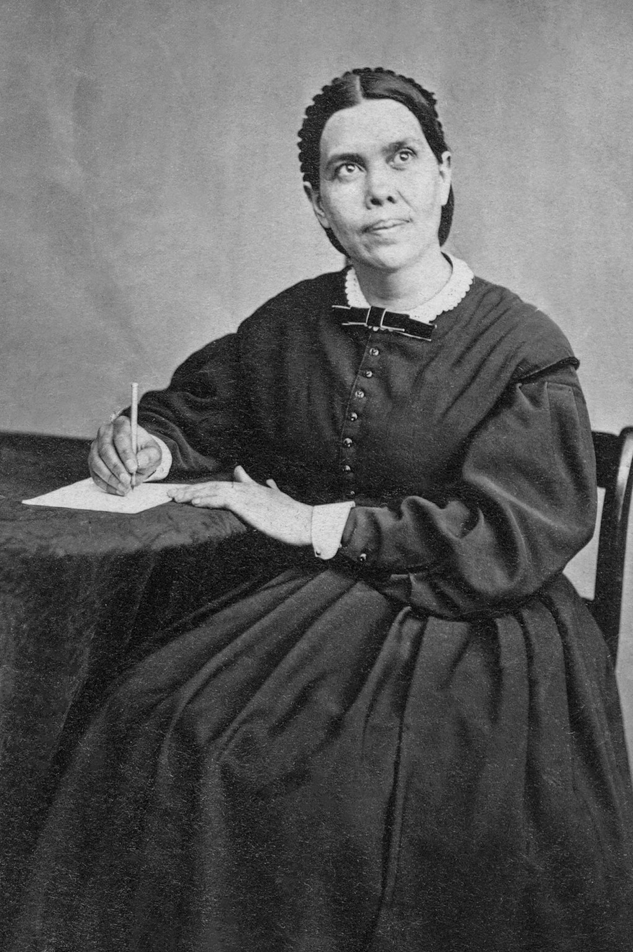

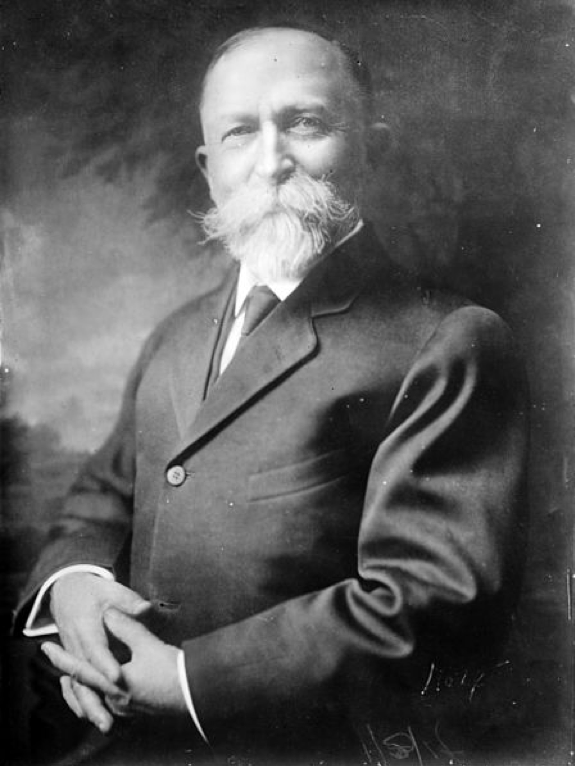

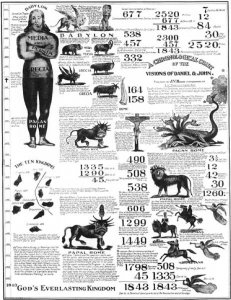

The Adventist movement began as an offshoot of the Millerite movement that spread over much of the United States in the early 1840s. An apocalyptic, millenarian community, Millerites adhered to New York farmer William Miller’s (1782-1849) scriptural calculations for the Second Coming of Christ, which was to occur in 1843-44. When Christ did not return, the inaccuracy of Miller’s predictions became known as the “Great Disappointment” and led to a splintering of the movement. A faction of remaining Adventists—those who continued to believe in an imminent return of Christ—formed a new community under the direction of spiritual visionary Ellen Gould Harmon White (1827-1915), her husband James White (1821-81), fellow revivalist Joseph Bates (1792-1872), and Hiram Edson (1806-82), whose views of the Second Coming became foundational in Adventist theology. Using Ellen White’s prophetic visions for salvation and seventh day (Saturday) worship as their guide, Adventists established a formal church in 1863 with the creation of the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists.

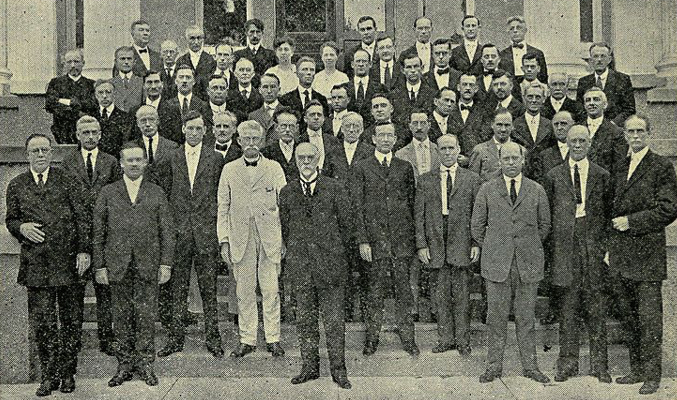

With roots in the Methodist and Baptist camp meeting culture of the “burned over” district in western and central New York, the new Adventist movement preached and practiced active evangelism. Missionary efforts by the Whites and their followers led to small communities of like-minded Adventists in Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, New York, Pennsylvania, and over the course of the next century, in the Midwest, western United States, and abroad as a global church. As membership increased, congregations were established, with local conferences or missions overseeing matters of Church polity, and union conferences or missions serving as regional authorities and grouped under large divisions.

Since its establishment in 1907, the Columbia Union Conference has overseen the Mid-Atlantic region, encompassing Adventist communities in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, the Chesapeake region, Ohio, Virginia, and West Virginia. By some estimations, the Pennsylvania conference and missions within the Columbia Union organized as early as 1851 under the direction of Hiram Edson and early Adventist missionary and former Millerite J.N. Andrews (1829-83). After more than two decades of evangelizing efforts, the Pennsylvania conference grew to more than one thousand members in over three dozen churches. In the century and a half since its inception, it expanded to include nearly one hundred churches, and more than ten thousand members.

Chesapeake and New Jersey Heritage

Companion conferences in the Chesapeake region and New Jersey likewise claimed ties to early Adventist missionaries like Joseph Bates, who visited the Chesapeake area in the 1850s. The Chesapeake Conference officially organized in 1899 and included Delaware, much of Maryland, and the District of Columbia. It subsequently expanded to a conference of more than seventy churches and fifteen thousand members. The New Jersey Conference quickly followed suit, organizing in 1901, and since that time developing into a region exceeding seventy-five churches and ten thousand members. In the late nineteenth century, Adventist missionaries in the Columbia Union Conference competed in particular with Catholics and Methodists for converts in the religious marketplace.

The Adventist movement has had a unique connection with “Philadelphia,” as the Pennsylvania city shares that name with one of the seven churches in the Book of Revelation (3:7). After the Millerite Great Disappointment of 1844, a contingent of Adventists believed themselves to be the fulfillment of that church—a chosen 144,000, who were marked by God for salvation. In this early period some inhabitants of Philadelphia and Baltimore hoped to be among these chosen few, attending revivalist camp meetings in the surrounding area as early as 1844. As the tradition grew, Ellen White’s visions often mentioned Philadelphia by name, along with New York, Boston, New Orleans, Cincinnati, and San Francisco—all viewed as urban centers of sin and corruption. Missionary efforts were concentrated in these areas, preaching temperance and health reform for spiritual purification, with a tent meeting in New Market, Virginia, in 1876. Though initially small, missions in Philadelphia gained strength with the establishment of the Columbia Union Conference, which convened there for the first time in 1907.

Service and missions have been at the core of Adventist practice and identity, with special attention to health and wellness, education, and civil rights. In its outreach, the church has used Adventist media outlets like the Adventist Review (established as The Present Truth in 1849) and Hope television channel (started in 2003). Adventist health missions have remained grounded in White’s 1863 vision for health reform, in which the prophetess called for vegetarianism, the avoidance of tobacco, caffeine, and alcohol, and regular exercise and hydration.

Battle Creek Sanitarium

In preparation for Christ’s return, “God’s diet” and wellness reforms were made available to Adventists and non-Adventists alike when the Whites and fellow Adventist John Harvey Kellogg (1852-1943) opened the Western Health Reform Institute (later the Battle Creek Sanitarium) in Michigan in 1866. The popularity of the “San” led to the construction of several more sanitariums in the U.S. and abroad, paving the way for a robust global Adventist hospital system. In Pennsylvania, the Adventist Whole Health Network continued this mission of the early church, offering community wellness programs mirroring White’s early visions for holistic health care.

Adventist children’s ministries have followed a comprehensive approach to education, stressing spiritual, physical, and academic growth. The church opened primary schools as early as the 1870s, with secondary schools, junior colleges, boarding schools, four-year colleges/universities, and medical schools following soon after. In the greater Philadelphia area, this has included primary and secondary schools in the Lehigh Valley and Lancaster, Pennsylvania, as well as in Wilmington, Delaware, and Trenton, New Jersey.

In the decades following Ellen White’s death in 1915, the structure of the church shifted through publications like the Working Policy (1926) and the Church Manual (1932). Outlining matters of governance and organization, these policies led to an evolution in the tradition, with increased growth in churches through the 1930s and 1940s. This resulted in the formation of churches inside and outside of urban areas and the organization in 1945 of predominantly Black Adventist churches in the Allegheny Conference East, which by the twenty-first century included several principally Hispanic congregations as well. The conference developed in size to nearly one hundred churches with more than thirty thousand members, including the Ebenezer Seventh-day Adventist Church in Philadelphia (established in 1931). This diversity in the church extended to Adventist converts in the Philadelphia area from Korea, Indonesia, Ghana, Brazil, Hungary, and Haiti.

From the beginning, the Adventist movement strongly advocated for service, both for followers and non-Adventists. Urban charities and missions in the Philadelphia region have provided vegetarian meals to those in need after Sunday services; offered community Bible studies, ESL courses, and health screenings at low or no cost; participated in disaster relief; actively supported new congregations in the process of “church planting”; and, through the volunteer-based Arise and Build program, erected new church structures for budding congregations in need. From a small denominational sect of roughly 3,500 in 1863, the Adventist tradition grew by 2019 into a global church of nearly twenty-five million.

Emily Bailey is Assistant Professor of Christian Traditions and Religions in the Americas at Towson University, Towson, Maryland. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- AEC: Our History (VisitAEC.org)

- A Look at the Columbia Union Conference's Beginnings (Columbia Union Conference)

- Chesapeake Conference History (Chesapeake Conference of Seventh-day Adventists)

- Seventh-day Adventist Church Pennsylvania Conference: What We Believe (Seventh-day Adventist Church: Pennsylvania Conference)

- Adventist Digital Library

- New Jersey Conference of Seventh-day Adventists: Vision and Mission (New Jersey Conference of Seventh-day Adventists)

- Race Issues in the Seventh-day Adventist Church: An Interview with Alvin Kibble and Benjamin Baker (YouTube)