Slavery and the Slave Trade

By James Gigantino | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

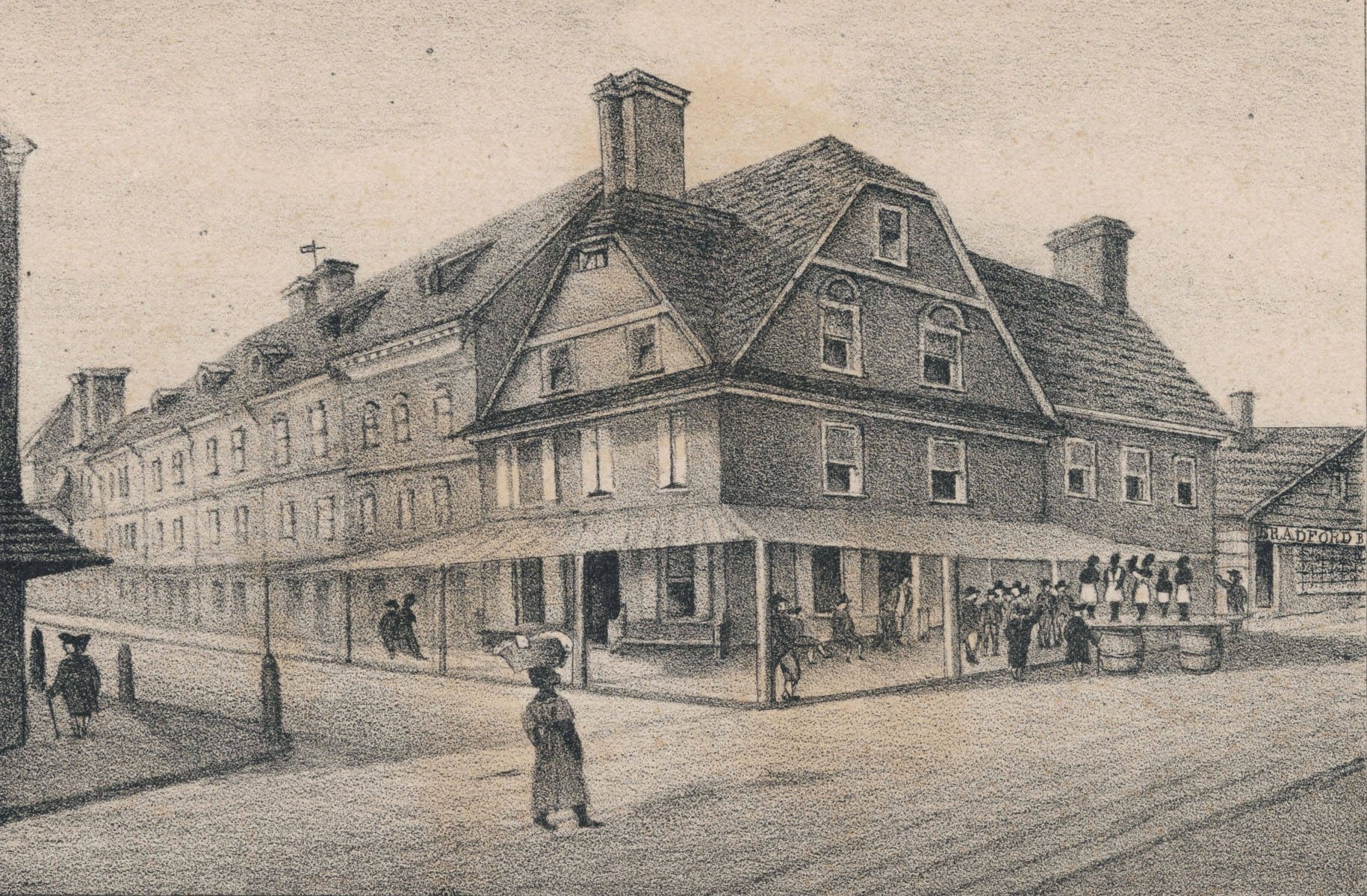

Slavery and the slave trade were central to the history of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Philadelphia as the region economically benefited from the institution and dealt with tensions created by slave trading, slave holding, and abolitionism. Early Philadelphia, an Atlantic trading hub, became both a focal point for the slave trade and a community of enslaved Africans. Slaves created their own family and social networks while simultaneously integrating into white Philadelphia, shaping the political, economic, and social course that the region took into the nineteenth century.

Slave labor was integral to the region even before William Penn (1644-1718) founded Pennsylvania. New Sweden colonists, whose settlement from 1638-1655 centered on present-day Wilmington, Delaware, and extended throughout the lower Delaware Valley, imported the first African slaves in the mid- to late seventeenth century. After Penn founded his colony, slavery continued to be integral to the infant city of Philadelphia and its environs with the first slave ship arriving in Philadelphia itself in 1684. Slaves filled labor needs in many occupations as the region developed a diverse economy. Colonists in New Jersey and Delaware utilized slavery in essentially the same ways, though planters in central and southern Delaware used slaves to grow tobacco, wheat, and other commodities.

The presence of indentured servants in the colonial period created a hybrid labor system in which the region’s indentured white laborers, free wage laborers, and slaves worked alongside each other. This system created flexibility for meeting labor needs as labor costs and supply fluctuated throughout the colonial period. Masters routinely hired out their slaves, which further added to the labor system’s flexibility and the regional impact of slavery. The hiring-out system allowed slaves to move throughout the region on long and short term contracts to various masters. Native Americans were occasionally among the enslaved until at least the middle of the eighteenth century, but most enslaved people were Africans or African descendants. By the 1710s, race-based slavery had developed and European colonists rationalized slavery by seeing Africans as barbaric, heathen, and therefore eligible for enslavement. Through Philadelphia’s port, like in other colonies, these ideas of race and slavery came into the region as merchants and sailors participated in the growth of Western slavery and the slave trade. By 1710, slaves constituted almost twenty percent of Philadelphia’s population; while the number of slaves increased until just before the American Revolution, reaching 1,375 in 1770 or just over eight percent of the total population.

Most Came from Caribbean

The slave trade represented a major part of the Philadelphia region’s relationship to the Atlantic world, the networks formed by trade, migration, and political associations between Europe, Africa, and the Americas. Slave ships outfitted in Philadelphia traveled to the West African coast to trade for slaves, though the majority of slaves who entered the region did not come from Africa directly. Most came after living for several years in the Caribbean with their masters or on slave ships whose masters had purchased them in the Caribbean for sale in the smaller North American market. These largely West African slaves filled labor shortages in the Philadelphia region, especially when disruptions limited the supply of indentured laborers. For example, when the Seven Years’ War interrupted the flow of indentured laborers, the Philadelphia region imported almost 1,300 slaves in a nine-year period, including many directly from Africa. By 1767, fifteen percent of Philadelphia households owned slaves. However, the slave trade to the region largely ended when Pennsylvania levied a high duty on imported slaves in 1773 in response to fears of slave revolt as well as calls to end the most horrid part of the institution of slavery. Most other colonies had also begun to limit or prohibit the slave trade by the beginning of the Revolution for similar reasons, including New Jersey and Delaware, a trend which continued when all but South Carolina and Georgia banned the trade in the aftermath of the Revolution.

Philadelphia’s enslaved men and women, as part of the region’s hybrid labor force, toiled for masters who in most cases owned only one or two slaves, which limited their ability to interact with other slaves. These small holdings also increased the masters’ ability to control most of their daily routine and limited the development of slave families and a distinct culture. Despite these arrangements, slaves managed to establish kinship networks around the city and its environs by interacting with one another in the city’s marketplaces and worship services. Ship captains also routinely used slave labor both in their homes as well as on their ships which allowed these slaves to create extensive Atlantic networks that allowed for an exchange of culture, information, and possibly the tools to achieve freedom. On the other hand, slaves who lived in rural areas similarly established these community networks when they traveled with their masters into Philadelphia to sell at the city’s markets or for other business purposes. These networks allowed enslaved Philadelphians to develop their own culture, social customs, and exercise their own religion. In this “underground” world beyond the control of white masters, slaves interacted with each other on a daily basis, forming romantic relationships, sustaining African cultural institutions, and maintaining family connections across long distances. This also allowed slaves to organize in resistance to the institution and advocate for abolition in the late eighteenth century.

Though early historians portrayed slavery in the North as benign, physical force and violence always mediated the master-slave relationship in the Philadelphia region. Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware, like all other colonies, passed strict regulations to govern enslaved labor in the early eighteenth century. These regulations limited slave movement, provided harsh punishment for violent acts against whites, and established rules for general slave conduct. As in the Caribbean and the American South, resistance took many forms, but running away became the most frequent method. Slaves left their owners regularly both as a way to reject their masters’ control as well as to maintain kinship ties with distant families and communities.

Discussions of abolitionism developed in tandem with slavery’s increase. In 1688, four Germantown Quakers protested against African slavery, which mirrored Quaker founder George Fox’s (1624-91) questioning of the institution. However, Quakers continued to hold slaves throughout the colonial period as few believed the practice immoral as long as owners treated their slaves fairly and without violence. In 1776, the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting banned its members from owning slaves or face disownment from the Society of Friends.

Gradual Abolition Act

Quakers and non-Quaker allies discussed abolition in the midst of the American Revolution. Abolitionists routinely used the same language that Patriots utilized in their quest for freedom from British “tyranny” or “enslavement” to highlight the hypocrisy of owning slaves amidst a crusade for freedom. In Pennsylvania, this revolutionary rhetoric motivated the state legislature to enact the first legislative emancipation in history: the Gradual Abolition Act of 1780. However, the Act of 1780 freed no slaves immediately. It only provided freedom for children born to slaves after its enactment. These children labored for their mothers’ masters for twenty-eight years and therefore, in effect, paid slaveholders the cost of their own freedom. These children, an entirely new legal category, entered a society that was unprepared to deal with their eventual freedom. This led many slaveholders to treat them as slaves, working, beating, and selling them in the same way as their parents. Slavery, therefore, died a very slow and painful death.

After 1780, the presence of slavery continued to be a concern in Pennsylvania as non-resident slaveholders regularly brought slaves into the state. This became even more problematic when Philadelphia became the nation’s capital from 1790 to 1800 and southern members of Congress arrived in the city with their slaves. George Washington, living in the President’s House, brought nine of his slaves with him. As a non-resident, the 1780 Abolition Act allowed Washington and other slaveholders to bring slaves into Pennsylvania for six months before mandating their freedom. Washington and other masters exploited a loophole in a “sojourner law,” which allowed them to continue to hold slaves in Pennsylvania indefinitely as long as their slaves traveled to another state at least every six months. Washington, for example, had his slaves cross the Delaware into New Jersey to restart the six-month limit or sent them periodically back to Mount Vernon. The extension of slavery that sojourner laws permitted led many abolitionists to call for their repeal in the 1830s and 1840s, thereby exacerbating sectional tensions in the years before the Civil War.

Slavery in New Jersey remained an important institution after the American Revolution as it provided much of the labor to repair the state’s economy after armies laid waste to the state during the war. By 1790, most of West Jersey (including present-day Sussex, Warren, Morris, Hunterdon, Mercer, Burlington, Salem, Gloucester, Cumberland, Atlantic, and Cape May Counties) was largely free of slavery due to Quaker influence. However, large portions of East Jersey (present-day Passaic, Bergen, Hudson, Essex, Union, Somerset, Middlesex, Monmouth, and Ocean Counties) retained it with some counties counting more than 15 percent of their population as enslaved. Lacking a strong abolitionist presence, New Jersey became the last northern state to adopt a gradual abolition law in 1804. Delaware, on the other hand, discussed gradual abolition but never approved it due to the slave-holding interests in the southern part of the state. However, along with the rest of the upper South, the state relaxed manumission standards and slavery gradually declined in the areas bordering Pennsylvania.

By the 1830s, slavery largely disappeared from the region, though because of the terms of gradual abolition it remained legal in Pennsylvania until 1847 and in New Jersey until 1846. Over the next several decades, Philadelphia’s status as a port city and its border with slave-holding Maryland and Delaware attracted increasing numbers of fugitive slaves from the South. Free Blacks also risked being kidnapped into slavery to feed the hungry labor markets of Louisiana and Mississippi. Concern over kidnapping led white and Black Philadelphians to action. For instance, Absalom Jones, a former slave and leading Black abolitionist and minister, helped author a 1799 petition with other free Blacks to Congress asking for revisions to the 1793 Fugitive Slave Law. When relief did not come from the federal government, Philadelphia’s Mayor Joseph Watson used city resources in the 1820s to recover slaves and freed Blacks kidnapped to the South. This new dimension of slavery continued debates over the institution in the state until the Civil War.

James Gigantino is an Assistant Professor of History at the University of Arkansas. He is currently working on a book project on slavery and abolition in New Jersey. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2012, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- Africans in America: Brotherly Love (PBS)

- Slavery and Servitude at Cliveden

- London Coffee House: Behind the Marker (Explore PA History)

- Teaching Unit: Fugitive Slaves: The Cost of Caring (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- The Transatlantic Slave Trade Primary Source Set (Digital Public Library of America)

- Penn unveils new findings on history with slavery (Daily Pennsylvanian)